- Page 2 and 3:

The Dawn of Drug Safety Myles D B S

- Page 4 and 5:

George Mann Publications Contents

- Page 6 and 7:

§ References .....................

- Page 8 and 9:

Mrs L Lake SRN, SCM for help with t

- Page 10 and 11:

and international bodies play a maj

- Page 12 and 13:

Mechanism of action Causality Predi

- Page 14 and 15:

possible blindness, paralysis of th

- Page 16 and 17:

Filipendula ulmaria or Spiraea ulma

- Page 18 and 19:

2. Laws and Regulations. a. Prevent

- Page 20 and 21:

Algeria, dated 7000-5000 BC, there

- Page 22 and 23:

Sennacharib 11 (705-681 BC), which

- Page 24 and 25:

(henbane), opium and colchicum. (Ma

- Page 26 and 27:

mandragora, mentha, myrrh, opium, p

- Page 28 and 29:

16. Hellebore (alias Christmas Rose

- Page 30 and 31:

clothes and head-bindings, and thei

- Page 32 and 33:

ecovered after a dose of a drug.’

- Page 34 and 35:

the Christian era it was well known

- Page 36 and 37:

given at such a time, it is sure to

- Page 38 and 39:

he strewed powdered Henbane, and li

- Page 40 and 41:

The second category of herbs was ca

- Page 42 and 43:

1 st quarter of the 2 nd century AD

- Page 44 and 45:

The Dark Ages from the 5th to the 8

- Page 46 and 47:

ecomes disordered, his tongue swell

- Page 48 and 49:

inspected at any time without warni

- Page 50 and 51:

done on any “new” product: 1. T

- Page 52 and 53:

drugs. It represents the first gove

- Page 54 and 55:

not written in the form of tables.

- Page 56 and 57:

idea of four humours: blood (sangui

- Page 58 and 59:

ordered pharmacists to prepare drug

- Page 60 and 61:

No mention of side effects. 1270 A

- Page 62 and 63:

population was approximately 6 mill

- Page 64 and 65:

ed as blood, red wine, Then would h

- Page 66 and 67:

time of his death in 1534 in three

- Page 68 and 69:

1497 Syphilis broke out for the fir

- Page 70 and 71:

1686 Stockholm ‘Pharmacopoeja Hol

- Page 72 and 73:

drugs, from the shores of the Red S

- Page 74 and 75:

medical tracts from Avicenna, Razie

- Page 76 and 77:

all manner of creatures of God crea

- Page 78 and 79:

powders of myrrh, of mastic, of cer

- Page 80 and 81:

swollen in the interior, that first

- Page 82 and 83:

mercury is the special best remedy

- Page 84 and 85:

78 Uncomes = whitlows will use it i

- Page 86 and 87:

nightshade; but not without great e

- Page 88 and 89:

may be chosen the best and most luc

- Page 90 and 91:

‘A New Herball: Wherein are conta

- Page 92 and 93:

such an enmity with blood of man.

- Page 94 and 95:

The surprise visitation was carried

- Page 96 and 97:

nature of it, unto this may be adde

- Page 98 and 99:

sometimes they so trouble the brain

- Page 100 and 101:

as you will use, and boil it 6. or

- Page 102 and 103:

Dose filthy; and much more after a

- Page 104 and 105:

Dichotomy In all people there is so

- Page 106 and 107:

it Venom, Venom! Poison, say they (

- Page 108 and 109:

or the dominions beyond thereof.’

- Page 110 and 111:

Quinsy = tonsillitis Spotted fever

- Page 112 and 113:

1652 Culpeper, Nicholas, (1616-1654

- Page 114 and 115:

Figure 7. The Expert Doctor’s Dis

- Page 116 and 117:

themselves with brawling and alterc

- Page 118 and 119:

principles of the art of physick’

- Page 120 and 121:

Poisons upon Animals, etc.’ Made

- Page 122 and 123:

First medical journal ‘Medicina C

- Page 124 and 125:

Closed in 1725 (Warren, http://www.

- Page 126 and 127:

for each drug especially for helleb

- Page 128 and 129:

hurry of the spirits, causes rest a

- Page 130 and 131:

3. 1736 Frederich Hoffmann wrote th

- Page 132 and 133:

Francois Chicanneau. This contains

- Page 134 and 135:

can only be obtained by a just acqu

- Page 136 and 137:

Pills about him, left Gilbert Jones

- Page 138 and 139:

George Key wrote ‘A dissertation

- Page 140 and 141:

sometimes excites convulsions.’ H

- Page 142 and 143:

drugs’ said of henbane: ‘The bl

- Page 144 and 145:

ut it would not become generally us

- Page 146 and 147:

hiccoughs*; convulsions; syncopes,

- Page 148 and 149:

avec leurs antidotes; rédigée d

- Page 150 and 151:

1780). 1781 ‘Observations on the

- Page 152 and 153:

emarked that it was a violent medic

- Page 154 and 155:

Figure 8 Arsenic © Wellcome Images

- Page 156 and 157:

oppression of the breast, fever, he

- Page 158 and 159:

of former authors on these points i

- Page 160 and 161:

Vernor and Hood, London, 1798. ‘I

- Page 162 and 163:

Vaccines pharmacovigilance data. Wh

- Page 164 and 165:

that I can find where the phrase

- Page 166 and 167:

Physician/scientist Drug taken ADRs

- Page 168 and 169:

Physician/scientist Drug taken ADRs

- Page 170 and 171:

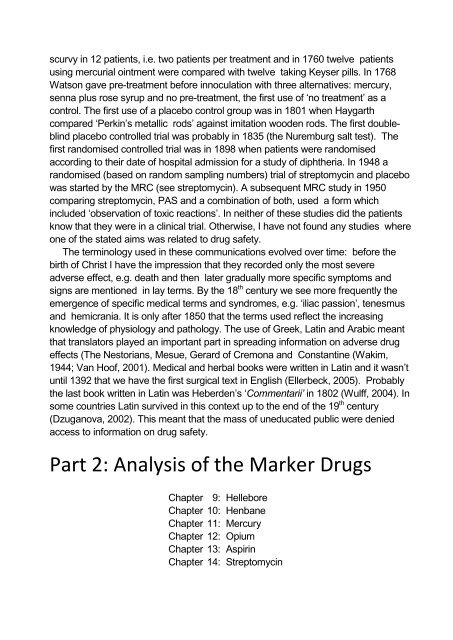

Chapter 7. 19 th Century A lchemy h

- Page 172 and 173:

White Hellebore: ‘violent purging

- Page 174 and 175:

medicine as potentized development

- Page 176 and 177:

vomiting, increase discharge of uri

- Page 178 and 179:

How many patients have they lost? H

- Page 180 and 181:

diarrhoea…If plentifully prescrib

- Page 182 and 183:

1841 Sir Astley Cooper gave the eff

- Page 184 and 185:

The UK House of Commons Select Comm

- Page 186 and 187:

Kolbe and Lautemann made synthetic

- Page 188 and 189:

predisposition that one cannot call

- Page 190 and 191:

this it may be noted that the major

- Page 192 and 193:

emulsion. To the strained emulsion,

- Page 194 and 195:

eruptions. The first study of a dru

- Page 196 and 197: ‘It presents several advantages o

- Page 198 and 199: as the charlatans continued to flou

- Page 200 and 201: digoxin. It was not until the explo

- Page 202 and 203: eported in Australia as early as th

- Page 204 and 205: 1907 Synthesis of arsphenamine (Sal

- Page 206 and 207: The bill was strongly opposed by th

- Page 208 and 209: James McDonagh, referring to Salava

- Page 210 and 211: erythema, spasmodic coryza, an atta

- Page 212 and 213: their confidence. Certainly the med

- Page 214 and 215: 1935 First use of prontosil red (su

- Page 216 and 217: groups admitted patients on alterna

- Page 218 and 219: These postulates governed toxicolog

- Page 220 and 221: some of the herbs: hellebore, hemlo

- Page 222 and 223: and treatment. It deals with methyl

- Page 224 and 225: USA, because less than 1% of new co

- Page 226 and 227: 1981). Dr Kelsey said at an open pu

- Page 228 and 229: Germany, particularly for use in ch

- Page 230 and 231: must be due to some recently introd

- Page 232 and 233: This of course will add to more rap

- Page 234 and 235: 1878) The latter being urticaria. 1

- Page 236 and 237: Poison the cow-pox, that the dispos

- Page 238 and 239: Persistence of drugs As explained a

- Page 240 and 241: have and have not had an exposure t

- Page 242 and 243: types of reactions: Lewin’s ‘Th

- Page 244 and 245: knowledge of medicine and science.

- Page 248 and 249: Mouth and throat tingling/burning o

- Page 250 and 251: s Sneezing (nasal use) 1586A,1657,

- Page 252 and 253: types of hellebore. There was a gap

- Page 254 and 255: 1546, 1565, 1752, 1789 Troubles in

- Page 256 and 257: Weakness 873, 1763, 1652, x x x Hea

- Page 258 and 259: ‘maketh man mad and foolish’ co

- Page 260 and 261: Mixtures: Donovan’s solution (Liq

- Page 262 and 263: Swollen tongue Ulceration of gums 1

- Page 264 and 265: Polyneuropathy enemy of the nerves

- Page 266 and 267: Headache 1711, 1733 1736, 1752 1788

- Page 268 and 269: 1806 Cough 1590, 1804 1806 x Conjun

- Page 270 and 271: The loss of hair has only been repo

- Page 272 and 273: the responsible organism, Treponema

- Page 274 and 275: Loss of memory 1586, 1619,1763 x Im

- Page 276 and 277: Antidiuretic effect 1776 urine inse

- Page 278 and 279: Nausea/vomiting # 1876 2,81,19 , 18

- Page 280 and 281: alkalosis * 1949 26 Hypoglycaemia 1

- Page 282 and 283: Drowsiness 1881 28 , 1884 86 , 1909

- Page 284 and 285: Papilloedema 1965 37 , 1965 37 Myop

- Page 286 and 287: Pancytopenia 1966 32 VI 1968 F D Me

- Page 288 and 289: SED = Meyler’s Side Effects of Dr

- Page 290 and 291: 29. Williams JO, Mengel CE, Sulliva

- Page 292 and 293: Aspirin. 57. Al-Abbasi AH. Salicyla

- Page 294 and 295: 282. Headache, giddiness, tinnitus,

- Page 296 and 297:

ullous eruption < 1 % and purpura.

- Page 298 and 299:

dose Aspirin produces generally its

- Page 300 and 301:

Douthwaite and Lintott first showed

- Page 302 and 303:

Chapter 14. Streptomycin treptomyci

- Page 304 and 305:

1946 September 28 th 1946 November

- Page 306 and 307:

1947 Forty patients. Dose 3.0 gm da

- Page 308 and 309:

cheeks, & the blood kept coming up

- Page 310 and 311:

‘By far the most important toxic

- Page 312 and 313:

In their study 1.6% of patients dis

- Page 314 and 315:

Renal dysfunction Vision- Yellow Di

- Page 316 and 317:

(Crofton, 2009). Asthma, pancytopen

- Page 318 and 319:

Ideal knowledge of an ADR How much

- Page 320 and 321:

Table 13. Number of first reports o

- Page 322 and 323:

Despite these actions the prescribe

- Page 324 and 325:

Remedy, the active ingredient was D

- Page 326 and 327:

on the lips (Thorwald, 1962) Uses:

- Page 328 and 329:

Comment: the side effects were seve

- Page 330 and 331:

SED 1952: habituation causes sympto

- Page 332 and 333:

and acuity, dementia, inability to

- Page 334 and 335:

have expected that it would have be

- Page 336 and 337:

the poor economic status of these a

- Page 338 and 339:

SED 1952: no mention. A warning was

- Page 340 and 341:

Withdrawn: over-the-counter sales w

- Page 342 and 343:

(ADEC, 1971). It is unlikely that c

- Page 344 and 345:

dose for six months, mice also deve

- Page 346 and 347:

symptoms.’ (Willcox, 1934). SED 1

- Page 348 and 349:

Comment: a Lancet editorial entitle

- Page 350 and 351:

1933 Dinitrophenol (2,4-dinitrophen

- Page 352 and 353:

1995). SED 1952: the same side effe

- Page 354 and 355:

Delay in recognition: None Delay in

- Page 356 and 357:

In 1958 Garrod reported an approxim

- Page 358 and 359:

purpura, toxic hepatitis, and aplas

- Page 360 and 361:

area and degree of inflammation. 19

- Page 362 and 363:

1952 Iproniazid (Marsilid) Was intr

- Page 364 and 365:

SED 1960: addiction frequently obse

- Page 366 and 367:

cutaneous sarcoidosis, erythema mul

- Page 368 and 369:

1957 Ethchlorvynol (Placidyl, Seren

- Page 370 and 371:

Official warnings were sent out in

- Page 372 and 373:

Delay in recognition: ≤ one year

- Page 374 and 375:

Withdrawn: USA 1962 Availability: n

- Page 376 and 377:

new original reports. Table 16. Num

- Page 378 and 379:

eporting (Griffin & Weber, 1986), b

- Page 380 and 381:

John Abraham and Helen Lawton Smith

- Page 382 and 383:

and nialamide; biguanides, e.g. buf

- Page 384 and 385:

see Hart PW in ‘Blood dyscrasias

- Page 386 and 387:

used in 1779 with reference to toba

- Page 388 and 389:

perhaps even stranger that there we

- Page 390 and 391:

of benefit to me.’ The first rule

- Page 392 and 393:

government authority including perf

- Page 394 and 395:

4) There was less risk of having an

- Page 396 and 397:

adverse effects more willingly. Now

- Page 398 and 399:

to restrict or withdraw a drug. ‘

- Page 400 and 401:

Armer RE and Morris ID. Trends in e

- Page 402 and 403:

Brookes R. (Richard). An introducti

- Page 404 and 405:

www.ordre.pharmacien.fr/upload/Synt

- Page 406 and 407:

of prescription drugs from worldwid

- Page 408 and 409:

Herbst Al, Vilfelder H and Posakanz

- Page 410 and 411:

Kereković M and Curković M. Olfac

- Page 412 and 413:

Med 2008;101: 148-155. Louis PCA. R

- Page 414 and 415:

MRC. At National Archives: FD1/6769

- Page 416 and 417:

Reynolds TB, Lapin AC, Peters RL an

- Page 418 and 419:

Solecki RS. Shanidar IV, a Neandert

- Page 420 and 421:

Vépan. Gaz Medic. De Strassb. 1865