(Bio)Fueling Injustice? - Europafrica

(Bio)Fueling Injustice? - Europafrica

(Bio)Fueling Injustice? - Europafrica

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

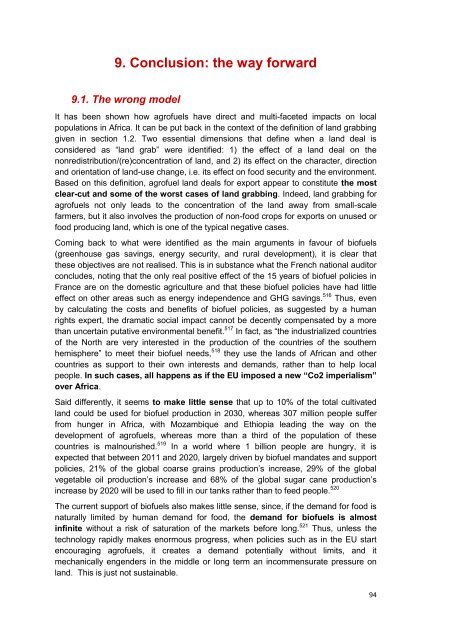

9. Conclusion: the way forward<br />

9.1. The wrong model<br />

It has been shown how agrofuels have direct and multi-faceted impacts on local<br />

populations in Africa. It can be put back in the context of the definition of land grabbing<br />

given in section 1.2. Two essential dimensions that define when a land deal is<br />

considered as “land grab” were identified: 1) the effect of a land deal on the<br />

nonredistribution/(re)concentration of land, and 2) its effect on the character, direction<br />

and orientation of land-use change, i.e. its effect on food security and the environment.<br />

Based on this definition, agrofuel land deals for export appear to constitute the most<br />

clear-cut and some of the worst cases of land grabbing. Indeed, land grabbing for<br />

agrofuels not only leads to the concentration of the land away from small-scale<br />

farmers, but it also involves the production of non-food crops for exports on unused or<br />

food producing land, which is one of the typical negative cases.<br />

Coming back to what were identified as the main arguments in favour of biofuels<br />

(greenhouse gas savings, energy security, and rural development), it is clear that<br />

these objectives are not realised. This is in substance what the French national auditor<br />

concludes, noting that the only real positive effect of the 15 years of biofuel policies in<br />

France are on the domestic agriculture and that these biofuel policies have had little<br />

effect on other areas such as energy independence and GHG savings. 516 Thus, even<br />

by calculating the costs and benefits of biofuel policies, as suggested by a human<br />

rights expert, the dramatic social impact cannot be decently compensated by a more<br />

than uncertain putative environmental benefit. 517 In fact, as “the industrialized countries<br />

of the North are very interested in the production of the countries of the southern<br />

hemisphere” to meet their biofuel needs, 518 they use the lands of African and other<br />

countries as support to their own interests and demands, rather than to help local<br />

people. In such cases, all happens as if the EU imposed a new “Co2 imperialism”<br />

over Africa.<br />

Said differently, it seems to make little sense that up to 10% of the total cultivated<br />

land could be used for biofuel production in 2030, whereas 307 million people suffer<br />

from hunger in Africa, with Mozambique and Ethiopia leading the way on the<br />

development of agrofuels, whereas more than a third of the population of these<br />

countries is malnourished. 519 In a world where 1 billion people are hungry, it is<br />

expected that between 2011 and 2020, largely driven by biofuel mandates and support<br />

policies, 21% of the global coarse grains production’s increase, 29% of the global<br />

vegetable oil production’s increase and 68% of the global sugar cane production’s<br />

increase by 2020 will be used to fill in our tanks rather than to feed people. 520<br />

The current support of biofuels also makes little sense, since, if the demand for food is<br />

naturally limited by human demand for food, the demand for biofuels is almost<br />

infinite without a risk of saturation of the markets before long. 521 Thus, unless the<br />

technology rapidly makes enormous progress, when policies such as in the EU start<br />

encouraging agrofuels, it creates a demand potentially without limits, and it<br />

mechanically engenders in the middle or long term an incommensurate pressure on<br />

land. This is just not sustainable.<br />

94