Annona Species Monograph.pdf - Crops for the Future

Annona Species Monograph.pdf - Crops for the Future

Annona Species Monograph.pdf - Crops for the Future

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

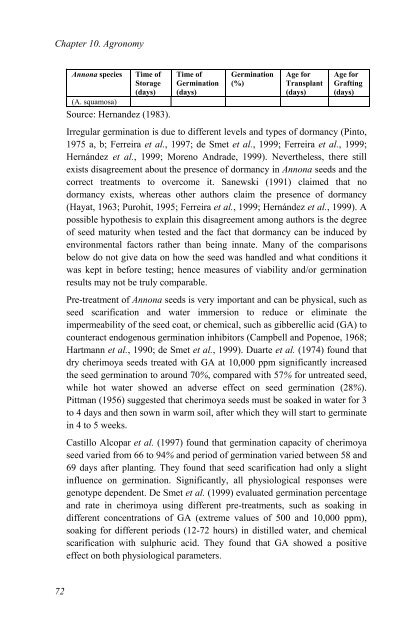

Chapter 10. Agronomy<br />

<strong>Annona</strong> species<br />

Time of<br />

Storage<br />

(days)<br />

Time of<br />

Germination<br />

(days)<br />

Germination<br />

(%)<br />

Age <strong>for</strong><br />

Transplant<br />

(days)<br />

Age <strong>for</strong><br />

Grafting<br />

(days)<br />

(A. squamosa)<br />

Source: Hernandez (1983).<br />

Irregular germination is due to different levels and types of dormancy (Pinto,<br />

1975 a, b; Ferreira et al., 1997; de Smet et al., 1999; Ferreira et al., 1999;<br />

Hernández et al., 1999; Moreno Andrade, 1999). Never<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong>re still<br />

exists disagreement about <strong>the</strong> presence of dormancy in <strong>Annona</strong> seeds and <strong>the</strong><br />

correct treatments to overcome it. Sanewski (1991) claimed that no<br />

dormancy exists, whereas o<strong>the</strong>r authors claim <strong>the</strong> presence of dormancy<br />

(Hayat, 1963; Purohit, 1995; Ferreira et al., 1999; Hernández et al., 1999). A<br />

possible hypo<strong>the</strong>sis to explain this disagreement among authors is <strong>the</strong> degree<br />

of seed maturity when tested and <strong>the</strong> fact that dormancy can be induced by<br />

environmental factors ra<strong>the</strong>r than being innate. Many of <strong>the</strong> comparisons<br />

below do not give data on how <strong>the</strong> seed was handled and what conditions it<br />

was kept in be<strong>for</strong>e testing; hence measures of viability and/or germination<br />

results may not be truly comparable.<br />

Pre-treatment of <strong>Annona</strong> seeds is very important and can be physical, such as<br />

seed scarification and water immersion to reduce or eliminate <strong>the</strong><br />

impermeability of <strong>the</strong> seed coat, or chemical, such as gibberellic acid (GA) to<br />

counteract endogenous germination inhibitors (Campbell and Popenoe, 1968;<br />

Hartmann et al., 1990; de Smet et al., 1999). Duarte et al. (1974) found that<br />

dry cherimoya seeds treated with GA at 10,000 ppm significantly increased<br />

<strong>the</strong> seed germination to around 70%, compared with 57% <strong>for</strong> untreated seed,<br />

while hot water showed an adverse effect on seed germination (28%).<br />

Pittman (1956) suggested that cherimoya seeds must be soaked in water <strong>for</strong> 3<br />

to 4 days and <strong>the</strong>n sown in warm soil, after which <strong>the</strong>y will start to germinate<br />

in 4 to 5 weeks.<br />

Castillo Alcopar et al. (1997) found that germination capacity of cherimoya<br />

seed varied from 66 to 94% and period of germination varied between 58 and<br />

69 days after planting. They found that seed scarification had only a slight<br />

influence on germination. Significantly, all physiological responses were<br />

genotype dependent. De Smet et al. (1999) evaluated germination percentage<br />

and rate in cherimoya using different pre-treatments, such as soaking in<br />

different concentrations of GA (extreme values of 500 and 10,000 ppm),<br />

soaking <strong>for</strong> different periods (12-72 hours) in distilled water, and chemical<br />

scarification with sulphuric acid. They found that GA showed a positive<br />

effect on both physiological parameters.<br />

72