- Page 5:

CONTENTSPageECONOMIC REPORT OF THE

- Page 9 and 10:

ECONOMIC REPORT OF THE PRESIDENTTo

- Page 11 and 12:

Monetary policy will play a critica

- Page 13 and 14:

Interest Rates and the U.S. Trade D

- Page 15:

THE ANNUAL REPORTOF THECOUNCIL OF E

- Page 19 and 20:

CONTENTSPageCHAPTER 1. FROM RECESSI

- Page 21 and 22:

PageConclusions 122CHAPTER 6. REVIE

- Page 23 and 24:

CHAPTER 1From Recession to Recovery

- Page 25 and 26:

slowed somewhat in the 1970s regard

- Page 27 and 28:

nal GNP growth is reflected in a sl

- Page 29 and 30:

inflation. More specifically, the A

- Page 31 and 32:

inflation rate, or with a 12 percen

- Page 33 and 34:

1988, an increase of about one-four

- Page 35 and 36: CHAPTER 2The Dual Problems of Struc

- Page 37 and 38: frequently associated with poor hea

- Page 39 and 40: Chart 2-2Distribution of Unemployme

- Page 41 and 42: Chart 2-4Distribution of Unemployme

- Page 43 and 44: These findings suggest several conc

- Page 45 and 46: Wage RigidityA number of studies sh

- Page 47 and 48: that these measures may have caused

- Page 49 and 50: Most young people find jobs or leav

- Page 51 and 52: to employers who hire youths. Tax c

- Page 53 and 54: defined broadly to include individu

- Page 55 and 56: ship between incomplete experience

- Page 57 and 58: CHAPTER 3The United States in the W

- Page 59 and 60: with 2.6 percent in the other Organ

- Page 61 and 62: TABLE 3-1 .—Structure ofthe U.S.

- Page 63 and 64: TABLE 3-2.—Trade balances by comm

- Page 65 and 66: concentrate on doing what it does r

- Page 67 and 68: the United States will depress pric

- Page 69 and 70: Chart 3-3Real Exchange Rates Of Maj

- Page 71 and 72: AN UNDERVALUED YEN?The explanations

- Page 73 and 74: arily reduced the international com

- Page 75 and 76: nancial markets. These transactions

- Page 77 and 78: TABLE 3-6.—Economic performance b

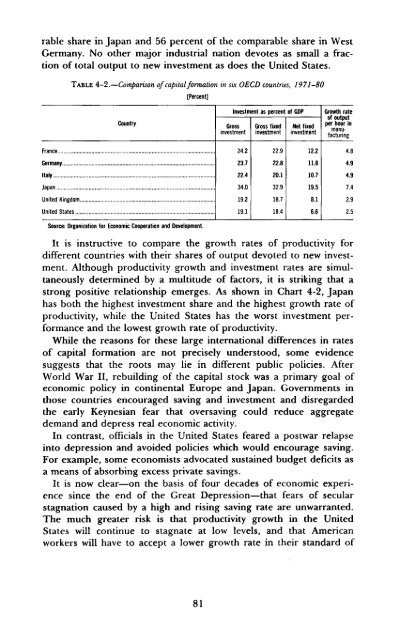

- Page 79 and 80: were undoubtedly a highly favorable

- Page 81 and 82: of lenders that some debtors will n

- Page 83 and 84: CHAPTER 4Increasing Capital Formati

- Page 85: ate of net investment was required,

- Page 89 and 90: During the 1970s, productivity grow

- Page 91 and 92: MEASURING NATIONAL SAVINGDomestic s

- Page 93 and 94: TAX RULES AND PERSONAL SAVINGMany e

- Page 95 and 96: on consumption taxation might also

- Page 97 and 98: Nevertheless, a number of economic

- Page 99 and 100: tion permitted businesses to deprec

- Page 101 and 102: A final problem under current tax l

- Page 103 and 104: fleeted efforts to deal with proble

- Page 105 and 106: egulation was probably not applicab

- Page 107 and 108: Aeronautics Board, for example, the

- Page 109 and 110: system resulted. Price controls, wh

- Page 111 and 112: NGPA, both controlled and decontrol

- Page 113 and 114: Price and allocation controls only

- Page 115 and 116: nications industries through the re

- Page 117 and 118: Several major pieces of legislation

- Page 119 and 120: tempt to set cartel rates would be

- Page 121 and 122: computer information and advertisin

- Page 123 and 124: of computer technology to the payme

- Page 125 and 126: trend by widening the sources and u

- Page 127 and 128: changes. That is, members can arbit

- Page 129 and 130: ceived to be a consequence of exces

- Page 131 and 132: lowest point in the post-World War

- Page 133 and 134: ing. Partly in response to the drop

- Page 135 and 136: Chart 6-3Ratio of Consumer Installm

- Page 137 and 138:

Chart 6-4RATIO1.85Real Inventory/Sa

- Page 139 and 140:

percent increase in real defense pu

- Page 141 and 142:

8.8 percent in 1981. These declines

- Page 143 and 144:

housing. Borrowing by the nonfinanc

- Page 145 and 146:

orous competitor for credit as usur

- Page 147 and 148:

1982 their share had risen to over

- Page 149 and 150:

TABLE 6-9.—Economic outlook for 1

- Page 151:

A critical element in achieving hea

- Page 155 and 156:

LETTER OF TRANSMITTALCOUNCIL OF ECO

- Page 157 and 158:

Report to the President on the Acti

- Page 159 and 160:

ety of interagency and internationa

- Page 161:

ence J. Kotlikoff (Yale University)

- Page 165 and 166:

CONTENTSNATIONAL INCOME OR EXPENDIT

- Page 167 and 168:

B-70. Mortgage debt outstanding by

- Page 169 and 170:

NATIONAL INCOME OR EXPENDITURETABLE

- Page 171 and 172:

TABLE B-2.—Gross national product

- Page 173 and 174:

19291933193919401941194219431944194

- Page 175 and 176:

TABLE B-5.—Changes in GNP and GNP

- Page 177 and 178:

TABLE B-7.—Gross national product

- Page 179 and 180:

TABLE B-9.—Gross national product

- Page 181 and 182:

TABLE B-ll.—Gross national produc

- Page 183 and 184:

TABLE B-13.—Output, costs, and pr

- Page 185 and 186:

TABLE B-14.—Personal consumption

- Page 187 and 188:

TABLE B-16.—Gross and net private

- Page 189 and 190:

TABLE B-18.—Inventories and final

- Page 191 and 192:

TABLE B-20.—Relation of national

- Page 193 and 194:

TABLE B-21.—National income by ty

- Page 195 and 196:

TABLE B-22.—Sources of personal i

- Page 197 and 198:

TABLE B-24.—Total and per capita

- Page 199 and 200:

Year or quarterTotalTotalTABLE B-26

- Page 201 and 202:

POPULATION, EMPLOYMENT, WAGES, AND

- Page 203 and 204:

TABLE B-29.—Noninstitutional popu

- Page 205 and 206:

TABLE B-31.—Selected employment a

- Page 207 and 208:

TABLE B-33.—Civilian unemployment

- Page 209 and 210:

TABLE B-35.—Unemployment by reaso

- Page 211 and 212:

TABLE B-37.— Wage and salary work

- Page 213 and 214:

TABLE B-39.—Average weekly earnin

- Page 215 and 216:

TABLE B-41.—Changes in productivi

- Page 217 and 218:

TABLE B-43-—Industrial production

- Page 219 and 220:

TABLE B-45.—Capacity utilization

- Page 221 and 222:

TABLE B-46.—New construction acti

- Page 223 and 224:

TABLE B-48.—Nonfarm business expe

- Page 225 and 226:

TABLE B-50.—Manufacturers' shipme

- Page 227 and 228:

Year or monthAllitemsPRICESTABLE B-

- Page 229 and 230:

TABLE B-53.—Consumer price indexe

- Page 231 and 232:

TABLE B-55.—Changes in consumer p

- Page 233 and 234:

TABLE B-57.—Producer price indexe

- Page 235 and 236:

TABLE B-58.—Producer price indexe

- Page 237 and 238:

TABLE B-59.—Producer price indexe

- Page 239 and 240:

MONEY STOCK, CREDIT, AND FINANCETAB

- Page 241 and 242:

TABLE B-63.—Commercial bank loans

- Page 243 and 244:

TABLE B-64.—Total funds raised in

- Page 245 and 246:

TABLE B-66.—Aggregate reserves of

- Page 247 and 248:

TABLE B-67 .—Bond yields and inte

- Page 249 and 250:

TABLE B-69.—Consumer installment

- Page 251 and 252:

TABLE B-71-—Mortgage debt outstan

- Page 253 and 254:

TABLE B-72.—Federal budget receip

- Page 255 and 256:

TABLE B-74.—Relation of Federal G

- Page 257 and 258:

TABLE B-76.—Federal Government re

- Page 259 and 260:

TABLE B-78.—State and local gover

- Page 261 and 262:

TABLE B-80.—Estimated ownership o

- Page 263 and 264:

CORPORATE PROFITS AND FINANCETABLE

- Page 265 and 266:

Year or quarterTABLE B-84.—Corpor

- Page 267 and 268:

TABLE B-86.—Relation of profits a

- Page 269 and 270:

TABLE B-88.—Determinants of busin

- Page 271 and 272:

TABLE B-9Q.~Current assets and liab

- Page 273 and 274:

TABLE B-92.—Common stock prices a

- Page 275 and 276:

AGRICULTURETABLE B-94.—Farm incom

- Page 277 and 278:

TABLE B-96.—Farm input use, selec

- Page 279 and 280:

TABLE B-98.—U.S. exports and impo

- Page 281 and 282:

INTERNATIONAL STATISTICSTABLE B-100

- Page 283 and 284:

TABLE B-101.—U.S. international t

- Page 285 and 286:

TABLE B-103.—U.S. merchandise exp

- Page 287 and 288:

TABLE B-105.—International invest

- Page 289 and 290:

TABLE B-107.— World trade balance

- Page 291 and 292:

TABLE B-109.—Growth rates in real

- Page 293:

TABLE B-lll.—Unemployment rate, a