COMPENDIO_DE_GEOLOGIA_Bolivia

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

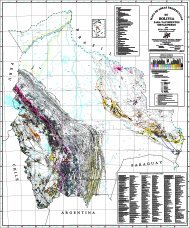

<strong>COMPENDIO</strong> <strong>DE</strong> <strong>GEOLOGIA</strong> <strong>DE</strong> BOLIVIA<br />

Faja estañífera<br />

La llamada "faja estañífera boliviana" (en realidad polimetálica con<br />

estaño dominante y desarrollada más allá de las fronteras bolivianas<br />

hasta el sudeste peruano por un lado y el noroeste argentino por el<br />

otro) se coloca entre las tres más extensas provincias estañíferas del<br />

mundo junto a aquellas de Malasia y de la cordillera de Sikhota Alin<br />

en Siberia oriental (donde ocurren mineralizaciones polimetálicas<br />

parecidas), y también entre las más ricas con sus enormes<br />

concentraciones metálicas de Llallagua (la mayor acumulación de<br />

estaño hipógeno a nivel mundial), Huanuni, Colquiri, Japo-Santa Fe-<br />

Morococala, Chorolque y otras que, por sí solas, representaban<br />

originalmente un potencial total de más de 1 Mt Sn. Dentro como<br />

fuera de unas 900 minas de estaño, este cinturón encierra además<br />

cuantiosos recursos de plata (el Cerro Rico de Potosí es el mayor<br />

yacimiento argentífero conocido), bismuto (cf. Tasna), wolfram,<br />

metales de base y oro; de tal modo que, globalmente, se le ha podido<br />

asignar más de los 3/4 de las menas metalíferas de <strong>Bolivia</strong><br />

(Heuschmidt 1979), país en cuya economía tuvo por supuesto<br />

siempre una incidencia fundamental.<br />

La faja estañífera se extiende por más de 1200 km de longitud, en<br />

dirección NW-SE a N-S como la faja polimetálica marginal que la<br />

flanquea al este, desde el sector peruano de Macusani (aprox. 14° de<br />

latitud S) hacia el noroeste hasta más allá de la mina argentina de<br />

Pirquitas (aprox. 23° S) hacia el sur. Confinada por lo esencial en el<br />

flanco W y las alturas del actual cinturón orogénico trasarco de la<br />

Cordillera Oriental, tiene en su partes septentrional y meridional un<br />

ancho medio de 40 km que va creciendo hasta un máximo del orden<br />

de 100 km en su parte central que corresponde a la porción más<br />

desarrollada hacia el este del oroclino boliviano.<br />

Además de su extensión y trascendencia minera, esta faja<br />

intracontinental posee una remarcable originalidad geológica y<br />

metalogénica en el marco centroandino. En primer lugar resalta la<br />

permanencia por más de 350 Ma (desde el Paleozoico Superior hasta<br />

el Reciente) de su especialización metálica bajo diferentes<br />

expresiones yacimentológicas y en un contexto geotectónico muy<br />

cambiante (Clark et al. 1984, Redwood 1993); permanencia de la que<br />

Lehmann (1990) ha dado la explicación petrológica citada más<br />

arriba, basada en las nociones de diferenciación avanzada de los<br />

magmas corticales metalotectos dentro de una corteza continental<br />

regionalmente muy gruesa y de sobreconcentración magmática e<br />

hidrotermal residual de su estaño en el ambiente moderadamente<br />

oxigenado de lutitas carbonosas de la cuenca eopaleozoica de la<br />

Cordillera Oriental. En segundo lugar queda ahora bien establecido<br />

que la geodinámica profunda de la actual faja estañífera fue mucho<br />

menos influenciada en todo tiempo por la subducción peripacífica o<br />

las paleosubducciones de la margen móvil sudamericana<br />

(Gondwana) que aquella de las fajas polimetálica y cuprífera del<br />

Altiplano y de la Cordillera Occidental, más epicontinentales: ello<br />

tanto en el Triásico-Jurásico durante el período distensivo<br />

protoandino como en el Oligo-Plioceno durante el ciclo compresivo<br />

andino propiamente dicho. Lo indica claramente el quimismo<br />

subalcalino peraluminoso de tipo S (serie ilmenita), de afinidad<br />

cortical y no mantélica en zona Benioff, de los granitoides triásicojurásicos<br />

y oligo-miocenos de este cinturón metalífero (Clark et al.<br />

1984, Kontak et al. 1984).<br />

The Tin Belt<br />

The so-called “<strong>Bolivia</strong>n tin belt” (actually, a polymetallic belt with<br />

predominance of tin, which developed beyond the <strong>Bolivia</strong>n borders<br />

into southeastern Peru, on one side, and into northwestern Argentina,<br />

on the other) ranks among three of the world’s most extensive tin<br />

provinces, together with those of Malasia and the Sikhota Alin Range<br />

in eastern Siberia (where there are similar polymetallic<br />

mineralizations), and also among the richest, with its enormous<br />

metallic concentrations in Llallagua (the largest hypogene tin<br />

accumulation worldwide), Huanuni, Colquiri, Japo - Santa Fe-<br />

Morococala, Chorolque, and others, which on their own represented<br />

originally a total potential exceeding 1 Mt Sn. In addition, both, in<br />

and outside around 900 tin mines, this belt holds copious resources<br />

including silver (the Cerro Rico of Potosí is the largest silver deposit<br />

known), bismuth (cf. Tacna), wolfram base metals and gold; thus, it<br />

was possible to assign to it more than 3/4 of the metal ores in <strong>Bolivia</strong><br />

(Heuschmidt 1979), a country in which it always had a fundamental<br />

economic incidence.<br />

With a NW-SE to N-S trend, the tin belt extends for a length of over<br />

1200 km, just like the marginal polimetallic belt that runs along with<br />

it to the east, from the Peruvian sector of Macusani (approx. 14°<br />

latitude S) towards the northwest, beyond the Argentine mine of<br />

Pirquitas (approx. 23° S) towards the south. Essentially confined to<br />

the W limb and the heights of the current back-arc orogenic belt of<br />

the Eastern Cordillera, it reaches a mean width of 40 km in its<br />

northern and meridional portions, increasing up to a maximum in the<br />

order of 100 km in its central portion, pertaining to the most<br />

developed portion east of the <strong>Bolivia</strong>n orocline.<br />

In addition to its extension and mining trascendence, this<br />

intracontinental belt has a remarkable geological and metallogenic<br />

originality in the Central Andean setting. First, the permanence of its<br />

metallic specialization under different depositional expressions and<br />

in a changing geotectonic context (Clark et al. 1984, Redwood 1993),<br />

for over 350 Ma (from the Upper Paleozoic to the Recent), stands<br />

out; this permanence was subject of the above-mentioned<br />

petrological explanation by Lehmann (1990), based on the notions of<br />

advanced differentiation of metallotect crustal magmas within a<br />

continental crust that is regionally very thick and has magmatic and<br />

residual hydrothermal overconcentration of its tin, in a moderately<br />

oxigenated environment of carbonous shale of the Eastern Cordillera<br />

Eo-Paleozoic basin. Second, it is now well established that, at all<br />

times, the deep geodynamics of the current tin belt was much less<br />

influenced by the peripacific subduction or the paleosubductions of<br />

the South American mobile margin (Gondwana) than that of the<br />

polymetallic and copper belts of the Altiplano and Western<br />

Cordillera, which were more epicontinental, both in the Triassic-<br />

Jurassic,during the proto-Andean distensive period and in the Oligo-<br />

Pliocene, during the Andean compressive cycle itself. This clearly<br />

indicates the S-type (ilmenite series) peraluminous subalkaline<br />

chemism of this metalliferous belt’s Triassic-Jurassic and Oligo-<br />

Miocene granitoid, with crustal and non-mantle affinity in the<br />

Benioff zone (Clark et al. 1984, Kontak et al. 1984).<br />

187