- Page 1:

UNIVERSIDADE DE SANTIAGO DE COMPOST

- Page 5:

DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOXIA INGLESA E

- Page 8 and 9:

pero que se ganaron o meu cariño c

- Page 10 and 11:

1.3.7. Text linguistic studies ....

- Page 12 and 13:

5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY ........

- Page 14 and 15:

6.3.1. Frequency of nominalizations

- Page 16 and 17:

Table 17. Dependents of -ing and Ro

- Page 19 and 20:

0. INTRODUCTION It has been pointed

- Page 21 and 22:

0. INTRODUCTION Chapter 1 offers a

- Page 23:

0. INTRODUCTION conclusions reached

- Page 26 and 27:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION wo

- Page 28 and 29:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION an

- Page 30 and 31:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION cl

- Page 32 and 33:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION th

- Page 34 and 35:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION 1.

- Page 36 and 37:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION co

- Page 38 and 39:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION [t

- Page 40 and 41:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION no

- Page 42 and 43:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION se

- Page 44 and 45:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION 1.

- Page 46 and 47:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION si

- Page 48 and 49:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION [n

- Page 50 and 51:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION Wh

- Page 52 and 53:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION Th

- Page 54 and 55:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION (1

- Page 56 and 57:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION le

- Page 58 and 59:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION be

- Page 60 and 61:

1. THE CONCEPT OF NOMINALIZATION Al

- Page 63 and 64:

2. -ING NOMINALS: ORIGINS AND DEVEL

- Page 65 and 66:

2. -ING NOMINALS: ORIGINS AND DEVEL

- Page 67 and 68:

2. -ING NOMINALS: ORIGINS AND DEVEL

- Page 69 and 70:

2. -ING NOMINALS: ORIGINS AND DEVEL

- Page 71 and 72:

2. -ING NOMINALS: ORIGINS AND DEVEL

- Page 73:

2. -ING NOMINALS: ORIGINS AND DEVEL

- Page 76 and 77:

3. NOMINAL COMPLEMENTATION AND ARGU

- Page 78 and 79:

3. NOMINAL COMPLEMENTATION AND ARGU

- Page 80 and 81:

3. NOMINAL COMPLEMENTATION AND ARGU

- Page 82 and 83:

3. NOMINAL COMPLEMENTATION AND ARGU

- Page 84 and 85:

3. NOMINAL COMPLEMENTATION AND ARGU

- Page 86 and 87:

3. NOMINAL COMPLEMENTATION AND ARGU

- Page 88 and 89:

3. NOMINAL COMPLEMENTATION AND ARGU

- Page 90 and 91:

3. NOMINAL COMPLEMENTATION AND ARGU

- Page 92 and 93:

3. NOMINAL COMPLEMENTATION AND ARGU

- Page 94 and 95:

3. NOMINAL COMPLEMENTATION AND ARGU

- Page 96 and 97:

3. NOMINAL COMPLEMENTATION AND ARGU

- Page 98 and 99:

3. NOMINAL COMPLEMENTATION AND ARGU

- Page 100 and 101:

3. NOMINAL COMPLEMENTATION AND ARGU

- Page 102 and 103:

3. NOMINAL COMPLEMENTATION AND ARGU

- Page 104 and 105:

3. NOMINAL COMPLEMENTATION AND ARGU

- Page 106 and 107:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 108 and 109:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 110 and 111:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 112 and 113:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 114 and 115:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 116 and 117:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 118 and 119:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 120 and 121:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 122 and 123:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 124 and 125:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 126 and 127:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 128 and 129:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 130 and 131:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 132 and 133:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 134 and 135:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 136 and 137:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 138 and 139:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 140 and 141:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 142 and 143:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 144 and 145:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 146 and 147:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 148 and 149:

4. RHETORIC AND THE WORLD OF SCIENC

- Page 150 and 151:

5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY English

- Page 152 and 153: 5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY Section

- Page 154 and 155: 5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY Table 3.

- Page 156 and 157: 5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY As can b

- Page 158 and 159: 5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY Table 6.

- Page 160 and 161: 5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY combinat

- Page 162 and 163: 5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY 5.2.1.2.

- Page 164 and 165: 5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY and aton

- Page 166 and 167: 5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY nominal

- Page 168 and 169: 5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY (Jespers

- Page 170 and 171: 5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY (105) An

- Page 172 and 173: 5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY some cas

- Page 174 and 175: 5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY (122) (.

- Page 176 and 177: 5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY respecti

- Page 178 and 179: 5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY By contr

- Page 180 and 181: 5. CORPORA AND METHODOLOGY of their

- Page 183 and 184: 6. FINDINGS 6. FINDINGS This chapte

- Page 185 and 186: 6. FINDINGS instance, the normalize

- Page 187 and 188: 6. FINDINGS in their writings since

- Page 189 and 190: 6. FINDINGS Table 11. Overall figur

- Page 191 and 192: 6. FINDINGS (151) And that is a way

- Page 193 and 194: 6. FINDINGS 6.1.2.1. Pre-head depen

- Page 195 and 196: 6. FINDINGS verbal -ing formations

- Page 197 and 198: 6. FINDINGS (164) M.Borrough in his

- Page 199 and 200: 6. FINDINGS As shown in the figure,

- Page 201: 6. FINDINGS (179) Lastly, it implye

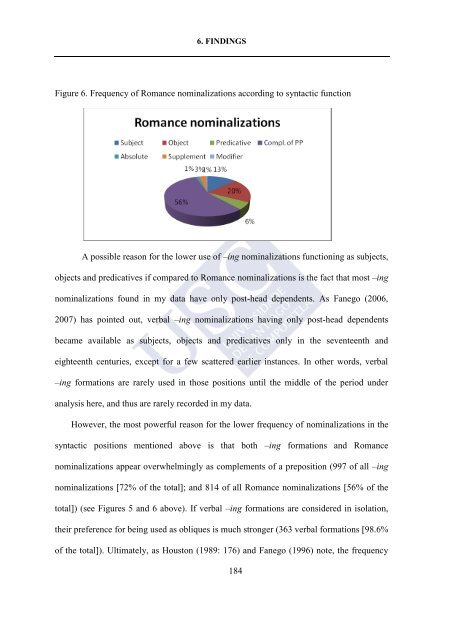

- Page 205 and 206: 6. FINDINGS complements of a prepos

- Page 207 and 208: 6. FINDINGS scientific and medical

- Page 209 and 210: 6. FINDINGS path-way to knowledge,

- Page 211 and 212: 6. FINDINGS The data presented abov

- Page 213 and 214: 6. FINDINGS Table 17. Dependents of

- Page 215 and 216: 6. FINDINGS (194) (...) so gentle m

- Page 217 and 218: 6. FINDINGS c. (...) he affirms tha

- Page 219 and 220: 6. FINDINGS expansion the point whe

- Page 221 and 222: 6. FINDINGS Figure 7. Earliest atte

- Page 223 and 224: 6. FINDINGS The data in Table 18 sh

- Page 225 and 226: 6. FINDINGS frequencies of 44.4 and

- Page 227 and 228: 6. FINDINGS that authors of surgica

- Page 229 and 230: 6. FINDINGS Table 20. Overall figur

- Page 231 and 232: 6. FINDINGS Figure 9. Suffixes used

- Page 233 and 234: 6. FINDINGS (210) Nor upon those wh

- Page 235 and 236: 6. FINDINGS Even when these texts w

- Page 237 and 238: 6. FINDINGS As can be seen from Tab

- Page 239 and 240: 6. FINDINGS vigilies, which may be

- Page 241 and 242: 6. FINDINGS of nominalizations in t

- Page 243: 6. FINDINGS Differences were also f

- Page 246 and 247: 7. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR

- Page 248 and 249: 7. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR

- Page 250 and 251: 7. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR

- Page 252 and 253:

7. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR

- Page 254 and 255:

7. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR

- Page 256 and 257:

7. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR

- Page 258 and 259:

7. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR

- Page 260 and 261:

7. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR

- Page 262 and 263:

7. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR

- Page 264 and 265:

7. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR

- Page 266 and 267:

REFERENCES Barton, David. 1994. Lit

- Page 268 and 269:

REFERENCES -----------. 1965. Aspec

- Page 270 and 271:

REFERENCES -----------. 1998. “De

- Page 272 and 273:

REFERENCES -----------. 2003. A Cog

- Page 274 and 275:

REFERENCES University of Pennsylvan

- Page 276 and 277:

REFERENCES Nevalainen, Terttu. 1999

- Page 278 and 279:

REFERENCES Russ, Charles V. J. 1982

- Page 280 and 281:

REFERENCES -----------. 1994b. “

- Page 283 and 284:

APPENDIX APPENDIX: ACTION NOMINALIZ

- Page 285 and 286:

APPENDIX and partly < accommodate +

- Page 287 and 288:

APPENDIX Tokens 8 Nominalization Ad

- Page 289 and 290:

APPENDIX heads with Cantharides, it

- Page 291 and 292:

APPENDIX Earliest attestation 1676

- Page 293 and 294:

APPENDIX he ceaseth not to be offic

- Page 295 and 296:

APPENDIX is to be done; direction,

- Page 297 and 298:

APPENDIX whych ben ioyned in wih th

- Page 299 and 300:

APPENDIX Tokens 17 Nominalization A

- Page 301 and 302:

APPENDIX signes of this disease: no

- Page 303 and 304:

APPENDIX Earliest attestation 1563

- Page 305 and 306:

APPENDIX Tokens brekynge/ for than

- Page 307 and 308:

APPENDIX Definition OED Bursting n.

- Page 309 and 310:

APPENDIX Nominalization Choosing Ba

- Page 311 and 312:

APPENDIX shutting; enclosing; drawi

- Page 313 and 314:

APPENDIX generally taken for any ki

- Page 315 and 316:

APPENDIX be rightly ordred & defend

- Page 317 and 318:

APPENDIX compression, and the offic

- Page 319 and 320:

APPENDIX Definition OED Concursion

- Page 321 and 322:

APPENDIX Conserving n., in same sen

- Page 323 and 324:

APPENDIX Example And therfore the s

- Page 325 and 326:

APPENDIX Earliest attestation c1374

- Page 327 and 328:

APPENDIX Tokens 14 Nominalization C

- Page 329 and 330:

APPENDIX Earliest attestation Examp

- Page 331 and 332:

APPENDIX Tokens Nominalization Base

- Page 333 and 334:

APPENDIX but y~ heet is meane witho

- Page 335 and 336:

APPENDIX bringing forth of offsprin

- Page 337 and 338:

APPENDIX Earliest attestation Examp

- Page 339 and 340:

APPENDIX detractynge of tyme. Gale,

- Page 341 and 342:

APPENDIX Base Definition Earliest a

- Page 343 and 344:

APPENDIX Nominalization Disclosing

- Page 345 and 346:

APPENDIX Earliest attestation 1563

- Page 347 and 348:

APPENDIX Base < Old French destempr

- Page 349 and 350:

APPENDIX Tokens is cured by diuerti

- Page 351 and 352:

APPENDIX Earliest attestation Examp

- Page 353 and 354:

APPENDIX Morbus. Tokens 1 Nominaliz

- Page 355 and 356:

APPENDIX Earliest attestation c1270

- Page 357 and 358:

APPENDIX Example Now it is most pro

- Page 359 and 360:

APPENDIX Nominalization Enjoying Ba

- Page 361 and 362:

APPENDIX Nominalization Base Defini

- Page 363 and 364:

APPENDIX examined. †1. A testing,

- Page 365 and 366:

APPENDIX observ’d, has any thing

- Page 367 and 368:

APPENDIX Base < Latin explānātiō

- Page 369 and 370:

APPENDIX Base Definition Earliest a

- Page 371 and 372:

APPENDIX excision or the applicatio

- Page 373 and 374:

APPENDIX Tokens 1 Nominalization Fa

- Page 375 and 376:

APPENDIX Earliest attestation Examp

- Page 377 and 378:

APPENDIX Nominalization Flying Base

- Page 379 and 380:

APPENDIX Nominalization Framing Bas

- Page 381 and 382:

APPENDIX Earliest attestation Examp

- Page 383 and 384:

APPENDIX continued in the state of

- Page 385 and 386:

APPENDIX Hooke, Life. Tokens 1 Nomi

- Page 387 and 388:

APPENDIX Nominalization Hurting Bas

- Page 389 and 390:

APPENDIX Example (...) only there i

- Page 391 and 392:

APPENDIX Tokens an instrument of tw

- Page 393 and 394:

APPENDIX through Consumptions; (...

- Page 395 and 396:

APPENDIX Tokens Morbus. 1 (verbal g

- Page 397 and 398:

APPENDIX Example The Dragon then si

- Page 399 and 400:

APPENDIX Tokens 1 Nominalization Ju

- Page 401 and 402:

APPENDIX Base < Old French lancier

- Page 403 and 404:

APPENDIX Example Tokens Nominalizat

- Page 405 and 406:

APPENDIX Nominalization Lucubration

- Page 407 and 408:

APPENDIX Base Measure (v) Definitio

- Page 409 and 410:

APPENDIX administration; an instanc

- Page 411 and 412:

APPENDIX Hippocrates [/28./] hauing

- Page 413 and 414:

APPENDIX fermentation, wherby the C

- Page 415 and 416:

APPENDIX which heer to repeate were

- Page 417 and 418:

APPENDIX Earliest attestation 1568

- Page 419 and 420:

APPENDIX offense) injury, wrong, an

- Page 421 and 422:

APPENDIX Nominalization Base Defini

- Page 423 and 424:

APPENDIX Hypochondriack patient is

- Page 425 and 426:

APPENDIX and knit againe after thei

- Page 427 and 428:

APPENDIX stem of perturbāre (to pe

- Page 429 and 430:

APPENDIX Definition OED Playing n.

- Page 431 and 432:

APPENDIX decay, or destruction; the

- Page 433 and 434:

APPENDIX Tokens 1 Nominalization Ba

- Page 435 and 436:

APPENDIX Tokens Nominalization Base

- Page 437 and 438:

APPENDIX publicly known; public not

- Page 439 and 440:

APPENDIX Nominalization Pursuance B

- Page 441 and 442:

APPENDIX Base Definition Earliest a

- Page 443 and 444:

APPENDIX declares it self in a more

- Page 445 and 446:

APPENDIX Tokens 2 Nominalization Ba

- Page 447 and 448:

APPENDIX Decoction, which is all le

- Page 449 and 450:

APPENDIX Nominalization Renting Bas

- Page 451 and 452:

APPENDIX Example Nevertheless in re

- Page 453 and 454:

APPENDIX Earliest attestation ?1425

- Page 455 and 456:

APPENDIX Nominalization Restraining

- Page 457 and 458:

APPENDIX Nominalization Riding Base

- Page 459 and 460:

APPENDIX Nominalization Base Defini

- Page 461 and 462:

APPENDIX comprehended the arte of p

- Page 463 and 464:

APPENDIX Base Definition Earliest a

- Page 465 and 466:

APPENDIX Tokens 4 Nominalization Sh

- Page 467 and 468:

APPENDIX because the visible vertue

- Page 469 and 470:

APPENDIX Cf. Spring v. 9. Of condit

- Page 471 and 472:

APPENDIX Tokens 1 Nominalization Ba

- Page 473 and 474:

APPENDIX tight, wrenching, etc.; th

- Page 475 and 476:

APPENDIX taking one group, matrix,

- Page 477 and 478:

APPENDIX Nominalization Base Defini

- Page 479 and 480:

APPENDIX something at a certain rat

- Page 481 and 482:

APPENDIX Tokens 17 (9 of them verba

- Page 483 and 484:

APPENDIX Nominalization Tension Bas

- Page 485 and 486:

APPENDIX Tokens 7 Nominalization Tr

- Page 487 and 488:

APPENDIX Definition Earliest attest

- Page 489 and 490:

APPENDIX Example Notwithstanding in

- Page 491 and 492:

APPENDIX Earliest attestation 1523

- Page 493 and 494:

APPENDIX Base Walk (v) Definition O

- Page 495 and 496:

APPENDIX Earliest attestation 1479-

- Page 497 and 498:

APPENDIX Base Wither (v) Definition

- Page 499 and 500:

RESUMEN EN ESPAÑOL RESUMEN EN ESPA

- Page 501 and 502:

RESUMEN EN ESPAÑOL verbos de los q

- Page 503 and 504:

RESUMEN EN ESPAÑOL El análisis de

- Page 505 and 506:

RESUMEN EN ESPAÑOL las formaciones

- Page 507:

RESUMEN EN ESPAÑOL Gotti, Maurizio