- Page 2 and 3:

GENERAL HISTORY OF AFRICA Ancient C

- Page 4 and 5:

UNESCO International Scientific Com

- Page 6 and 7:

Contents List of figures ix List of

- Page 8 and 9:

24 West Africa before the seventh c

- Page 10 and 11:

List of figures 24.4 The Tichitt re

- Page 12 and 13:

List of plates 3.6 Tame pelicans 13

- Page 14 and 15:

List of plates 15.3 Inscription fro

- Page 16 and 17:

Acknowledgements for plates Polish

- Page 18 and 19:

Introduction G. MOKHTAR with the co

- Page 20 and 21:

Introduction the documents at their

- Page 22 and 23:

Introduction is also wide open to t

- Page 24 and 25:

Introduction increasingly threatene

- Page 26 and 27:

Introduction used a natural calenda

- Page 28 and 29:

Introduction eighteenth to twentiet

- Page 30 and 31:

Introduction the very root of the d

- Page 32 and 33:

Introduction statues of the Pharaoh

- Page 34 and 35:

Introduction know whether a given s

- Page 36 and 37:

Introduction arms, the river itself

- Page 38 and 39:

Introduction religious purposes or

- Page 40 and 41:

Introduction must have been there t

- Page 43 and 44:

plate intro. i Onslaught on the Nil

- Page 45 and 46:

Origin of the ancient Egyptians CHE

- Page 47 and 48:

Origin of the ancient Egyptians the

- Page 49 and 50:

Origin of the ancient Egyptians It

- Page 51 and 52:

Origin of the ancient Egyptians The

- Page 53 and 54:

Origin of the ancient Egyptians Mel

- Page 55 and 56:

Origin of the ancient Egyptians reg

- Page 57 and 58:

Origin of the ancient Egyptians of

- Page 59 and 60:

Origin of the ancient Egyptians sch

- Page 61 and 62:

Origin of the ancient Egyptians The

- Page 63 and 64:

PRESENT kef i kef ek kef et kefef k

- Page 65 and 66:

Origin of the ancient Egyptians Egy

- Page 67 and 68:

Origin of the ancient Egyptians Con

- Page 69 and 70:

Origin of the ancient Egyptians sci

- Page 71 and 72:

plate 1.5 Libyan prisoner PLATE 1.6

- Page 73 and 74:

plate 1. 12 Cheops, Pharaoh of the

- Page 75 and 76:

* JÙ&&&L plate i. i 8 Statue of th

- Page 77 and 78:

I Symposium on the peopling of anci

- Page 79 and 80:

Annex to Chapter i individuals. Van

- Page 81 and 82:

Annex to Chapter i collaboration of

- Page 83 and 84:

Annex to Chapter i lexicological an

- Page 85 and 86:

Annex to Chapter i None of the part

- Page 87 and 88:

Annex to Chapter i up to the predyn

- Page 89 and 90:

Annex to Chapter i when the Kushite

- Page 91 and 92:

Annex to Chapter i would be used wi

- Page 93 and 94:

Annex to Chapter i considerably enl

- Page 95 and 96:

Annex to Chapter i stakingly resear

- Page 97 and 98:

Annex to Chapter i 1972 and again i

- Page 99 and 100:

Annex to Chapter i in the overall p

- Page 101 and 102:

FIG. 2.1 The Nile from the Third Ca

- Page 103 and 104:

Pharaonic Egypt different somatic g

- Page 105 and 106:

NEW KINGDOM 4 • *> — ItS ¡SSÍ

- Page 107 and 108:

Pharaonic Egypt were filled by coun

- Page 109 and 110:

Pharaonic Egypt written in cursive

- Page 111 and 112:

Pharaonic Egypt There were several

- Page 113 and 114:

Pharaonic Egypt Old Kingdom ended a

- Page 115 and 116:

Pharaonic Egypt certain other gods

- Page 117 and 118:

Pharaonic Egypt reflect the existen

- Page 119 and 120:

Pharaonic Egypt Joppa by General Dj

- Page 121 and 122:

Pharaonic Egypt eventually changed

- Page 123 and 124:

Pharaonk Egypt another has not yet

- Page 125 and 126:

Pharaonic Egypt Persian period 45 I

- Page 127 and 128:

plates 2.4-2.9 Treasures of Tutankh

- Page 129 and 130:

plate 2.9 Anubis at the entry to th

- Page 131 and 132:

Pharaonic Egypt: society, economy a

- Page 133 and 134:

Pharaonic Egypt: society, economy a

- Page 135 and 136:

Pharaonic Egypt: society, economy a

- Page 137 and 138:

Pharaonic Egypt: society, economy a

- Page 139 and 140:

Pharaonic Egypt: society, economy a

- Page 141 and 142:

Pharaonic Egypt: society, economy a

- Page 143 and 144:

Pharaonic Egypt: society, economy a

- Page 145 and 146:

Pharaonic Egypt: society, economy a

- Page 147 and 148:

Pharaonic Egypt: society, economy a

- Page 149 and 150:

Pharaonic Egypt: society, economy a

- Page 151 and 152:

w.%W*£ ^¿ 1-" **^% - plate 3.4 Re

- Page 153 and 154:

plate 3.9 Discoveries made by the F

- Page 155 and 156:

Egypt's relations with the rest of

- Page 157 and 158:

Egypt's relations with the rest of

- Page 159 and 160:

Egypt's relations with the rest of

- Page 161 and 162:

Egypt's relations with the rest of

- Page 163 and 164:

Egypt's relations with the rest of

- Page 165 and 166:

Egypt's relations with the rest of

- Page 167 and 168:

Egypt's relations with the rest of

- Page 169 and 170:

Egypt's relations with the rest of

- Page 171 and 172:

plate 4.1 The tribute of Libyan pri

- Page 173 and 174:

The legacy of Pharaonic Egypt R.-EL

- Page 175 and 176:

The legacy of Pharaonic Egypt This

- Page 177 and 178:

The legacy of Pharaonic Egypt manne

- Page 179 and 180:

The legacy of Pharaonic Egypt Egypt

- Page 181 and 182:

The legacy of Pharaonic Egypt and r

- Page 183 and 184:

The legacy of Pharaonic Egypt case

- Page 185 and 186:

The legacy ofPhar aortic Egypt Two

- Page 187 and 188:

The legacy of Pharaonic Egypt Papyr

- Page 189 and 190:

The legacy of Pharaonic Egypt its p

- Page 191 and 192:

The legacy of Pharaortic Egypt an i

- Page 193 and 194:

The legacy of Pharaonic Egypt distr

- Page 195 and 196:

The legacy of Pharaonic Egypt force

- Page 197 and 198:

4 WTT \ .:- plate 5.3 Discoveries m

- Page 199 and 200:

, - j plate 5.7 Town planning: layo

- Page 201 and 202:

plate 5.13 Ramses II (fluids techni

- Page 203 and 204:

Egypt in the hellenistic era they h

- Page 205 and 206:

Egypt in the hellenistic era Part o

- Page 207 and 208:

Egypt in the Hellenistic era runs:

- Page 209 and 210:

Egypt in the Hellenistic era In the

- Page 211 and 212:

Egypt in the Hellenistic era the na

- Page 213 and 214:

Egypt in the Hellenistic era exist

- Page 216 and 217:

Egypt in the hellenistic era Satyru

- Page 218 and 219:

Egypt in the hellenistic era worksh

- Page 220 and 221:

Egypt in the Hellenistic era of Cyr

- Page 222 and 223:

Egypt in the Hellenistic era own ch

- Page 224 and 225:

Î?M plate 6.1 Lighthouse at Alexan

- Page 226 and 227:

plate 6.7 A fragment of a bronze ba

- Page 228 and 229:

Egypt under Roman domination theref

- Page 230 and 231:

Egypt under Roman domination had a

- Page 232 and 233:

Egypt under Roman domination Antino

- Page 234 and 235:

Egypt under Roman domination victor

- Page 236 and 237:

Egypt under Roman domination In thi

- Page 238 and 239:

Egypt under Roman domination well v

- Page 240 and 241:

Egypt under Roman domination instal

- Page 242 and 243:

a) Roman baths and hypocaust b) Rom

- Page 244 and 245:

PLATE 7.7 Baouit painting plate 7.8

- Page 246 and 247:

Mediterranean Sea i i i 500 km CENT

- Page 248 and 249:

Egypt FärasBÜheri^Wadi Haifa jebe

- Page 250 and 251:

The importance of Nubia: a link bet

- Page 252 and 253:

The importance of Nubia: a link bet

- Page 254 and 255:

The importance of Nubia: a link bet

- Page 256 and 257:

The importance of Nubia: a link bet

- Page 258 and 259:

The importance of Nubia: a link bet

- Page 260 and 261:

The importance of Nubia: a link bet

- Page 262 and 263:

The importance of Nubia: a link bet

- Page 264 and 265:

Nubia before Napata (-3100 to -750)

- Page 266 and 267:

Nubia before Napata ( to éÉÊÊ^

- Page 268 and 269:

Nubia before Napata ( to 750) fig.

- Page 270 and 271:

Nubia before Napata ( — JIOO to

- Page 272 and 273:

Nubia before Napata ( jioo to 750)

- Page 274 and 275:

Nubia before Napata (—3100 to —

- Page 276 and 277:

FIG. 9.7 Nubia, 1580 before our era

- Page 278 and 279:

Nubia before Napata ( — j/oo to

- Page 280 and 281:

Nubia befare Napata ( — jioo to

- Page 282 and 283:

Kerma culture Nubia before Napata (

- Page 284 and 285:

Nubia before Napata (—3100 to —

- Page 286 and 287:

Nubia before Napata ( — 3100 to

- Page 288 and 289:

Nubia before Napata ( — 3100 to

- Page 290 and 291:

Nubia before Napata (—3100 to —

- Page 292 and 293:

Nubia before Napata (—jioo to —

- Page 294 and 295:

plate 9.1 A selection of Kerma pott

- Page 296 and 297:

plate 9.8 Kerma pottery plate 9.9 T

- Page 298 and 299:

FIG. io. i Meroitk sites

- Page 300 and 301:

The empire of Kush: Napata and Mero

- Page 302 and 303:

The empire of Kush: Napata and Mero

- Page 304 and 305:

The empire of Kush: Napata and Mero

- Page 306 and 307:

The empire of Kush: Napata and Mero

- Page 308 and 309:

The empire of Kush: Napata and Mero

- Page 310 and 311:

The empire of Kush: Napata and Mero

- Page 312 and 313:

The empire of Kush: Napata and Mero

- Page 314 and 315:

The empire o/Kusft: Napata and Mero

- Page 316 and 317:

plate 10.4 Painted blue glassware o

- Page 318 and 319:

The civilization of Napata and Mero

- Page 320 and 321:

The civilization of Napata and Mero

- Page 322 and 323:

The civilization of Napata and Mero

- Page 324 and 325:

The civilization of Napata and Mero

- Page 326 and 327:

The civilization of Napata and Mero

- Page 328 and 329:

The civilization of Napata and Mero

- Page 330 and 331:

The civilization of Napata and Mero

- Page 332 and 333:

The civilization of Napata and Mero

- Page 334 and 335:

The civilization of Napata and Mero

- Page 336 and 337:

The civilization of Napata and Mero

- Page 338 and 339:

The civilization of Napata and Mero

- Page 340 and 341:

The civilization of Napata and Mero

- Page 342 and 343:

plate i 1.5 Various pieces ofMeroit

- Page 344 and 345:

plate i i .7 King Arnekhamani:from

- Page 346 and 347:

FIG. 12. i The Nile from the First

- Page 349 and 350:

The spreading of Christianity in Nu

- Page 352 and 353:

The spreading of Christianity in Nu

- Page 354 and 355:

The spreading of Christianity in Nu

- Page 356 and 357:

The spreading of Christianity in Nu

- Page 358 and 359:

The spreading of Christianity in Nu

- Page 360 and 361:

x vWM r* if -* plate 12.2 Sandstone

- Page 362 and 363:

Pre-Aksumite culture H. DE CONTENSO

- Page 364 and 365:

Pre-Aksumite culture They merely te

- Page 366 and 367:

Pre-Aksumite culture façades, whic

- Page 368 and 369:

Pre-Aksumite culture and is much mo

- Page 370 and 371:

Pre-Aksumite culture to light in so

- Page 372 and 373:

Pre-Aksumite culture Gobochela repr

- Page 374 and 375:

Pre-Aksumite culture The solar cult

- Page 376 and 377:

Pre-Aksumite culture this group con

- Page 378 and 379:

Pre-Aksumite culture sanctuaries is

- Page 380 and 381:

Pre-Aksumite culture material found

- Page 382 and 383:

plate 13.3 Incense altar of Addi Ga

- Page 384 and 385:

The civilization of Aksum from the

- Page 386 and 387:

The civilization of Aksum from the

- Page 388 and 389:

The civilization of Aksum from the

- Page 390 and 391:

The civilization of Aksum from the

- Page 392 and 393:

The civilization ofAksum from the f

- Page 394 and 395:

The civilization of Aksum from the

- Page 396 and 397:

The civilization of Aksum from the

- Page 398 and 399:

The civilization of Aksum from the

- Page 400 and 401:

plate 1 4. i Aerial photograph of A

- Page 402 and 403:

Aksum: political system, economics

- Page 404 and 405:

Aksum: political system, economics

- Page 406 and 407:

Aksum: political system, economics

- Page 408 and 409:

Aksum: political system, economics

- Page 410 and 411:

Aksum: political system, economics

- Page 412 and 413:

Aksum: political system, economics

- Page 414 and 415:

Aksum: political system, economics

- Page 416 and 417:

Aksum: political system, economics

- Page 418 and 419:

Aksum: political system, economics

- Page 420 and 421:

Aksum: political system, economics

- Page 422 and 423:

Christian Aksum TEKLE TSADIK MEKOUR

- Page 424 and 425:

Christian Aksum the Jews and that o

- Page 426 and 427:

Christian Aksutn But probably the A

- Page 428 and 429:

The spread of Christianity Christia

- Page 430 and 431:

Christian Aksum denying that Christ

- Page 432 and 433:

Christian Aksum Yeha bear witness t

- Page 434 and 435:

Christian Aksum retaliation among t

- Page 436 and 437:

Christian Aksum this slaughter, Chr

- Page 438 and 439:

Christian Aksum Yet, Ezana boasts o

- Page 440 and 441:

Christian Aksum In reading this boo

- Page 442 and 443:

plate 16.1 Paintingfrom the church

- Page 444 and 445:

The proto-Berbers J. DESANGES The B

- Page 446 and 447:

The proto-Berbers peopling of the M

- Page 448 and 449:

The proto-Berbers that water was mo

- Page 450 and 451:

The proto-Berbers The proto-Berbers

- Page 452 and 453:

The proto-Berbers An inscription on

- Page 454 and 455:

The proto-Berbers The origins of th

- Page 456 and 457:

The proto-Berbers Such tomb furnitu

- Page 458 and 459:

The proto-Berbers fresh water, in p

- Page 460 and 461:

The proto-Berbers Poseidon, while t

- Page 462 and 463:

The Carthaginian period B. H. WARMI

- Page 464 and 465:

The Carthaginian period The long se

- Page 466 and 467:

The Carthaginian period and finally

- Page 468 and 469:

The empire of Carthage The Carthagi

- Page 470 and 471:

The Carthaginian period family in t

- Page 472 and 473: Saharan trade The Carthaginian peri

- Page 474 and 475: The Carthaginian period after the R

- Page 476 and 477: The Carthaginian period to Carthage

- Page 478 and 479: The Carthaginian period geopolitica

- Page 480 and 481: The Carthaginian period Syphax's de

- Page 482 and 483: The Carthaginian period of north-ea

- Page 484 and 485: The Carthaginian period kingdoms sa

- Page 486 and 487: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 488: 467

- Page 491 and 492: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 493 and 494: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 495: ^ .«s S 473

- Page 498 and 499: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 500 and 501: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 502 and 503: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 504 and 505: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 506 and 507: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 508 and 509: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 510 and 511: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 512 and 513: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 514 and 515: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 516 and 517: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 518 and 519: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 520 and 521: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 524 and 525: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 526 and 527: The Roman and post-Roman period in

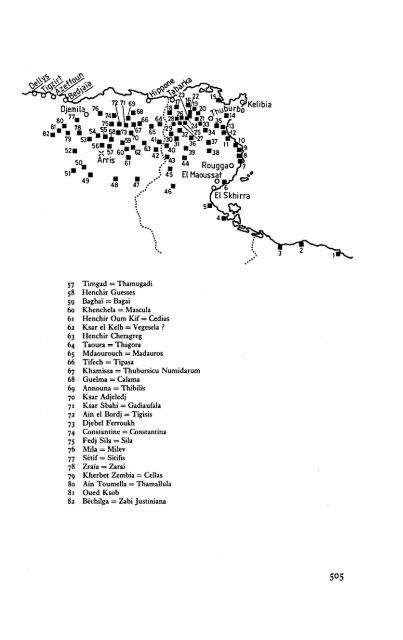

- Page 528 and 529: 57 Timgad = Thamugadi 58 Henchir Gu

- Page 530 and 531: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 532 and 533: The Roman and post-Roman period in

- Page 534 and 535: plate 19. i Mosaic from Sousse: Vir

- Page 536 and 537: PLATE 19.7 (left) Djemila (ancient

- Page 538 and 539: PLATE 19.12 Haïdra (Tunisia): Byza

- Page 540 and 541: 0 The Sahara in classical antiquity

- Page 543 and 544: KEY i Resseremt, near Akjoujt, Maur

- Page 545 and 546: The Sahara in classical antiquity o

- Page 547 and 548: The Sahara in classical antiquity N

- Page 549 and 550: The Sahara in classical antiquity t

- Page 551 and 552: The Sahara in classical antiquity S

- Page 553 and 554: The Sahara in classical antiquity m

- Page 555 and 556: The Sahara in classical antiquity d

- Page 557 and 558: The Sahara in classical antiquity k

- Page 559 and 560: PLATE 20.2 The tomb of 'Queen Tin H

- Page 561 and 562: 21 Introduction to the later prehis

- Page 563 and 564: FIG. 21. i Hypotheses concerning th

- Page 565 and 566: Introduction to the later prehistor

- Page 567 and 568: Introduction to the later prehistor

- Page 569 and 570: Introduction to the later prehistor

- Page 571 and 572: Introduction to the later prehistor

- Page 574 and 575:

Introduction to the later prehistor

- Page 576 and 577:

Introduction to the later prehistor

- Page 578 and 579:

Introduction to the later prehistor

- Page 580 and 581:

22 The East African coast and its r

- Page 582 and 583:

The East African coast and its role

- Page 584 and 585:

The East African coast and its role

- Page 586 and 587:

The East African coast and its role

- Page 588 and 589:

The East African coast and its role

- Page 590 and 591:

The East African coast and its role

- Page 592 and 593:

The East African coast and its role

- Page 594 and 595:

The East African coast and its role

- Page 596 and 597:

The East African coast and its role

- Page 598:

ai en 3 .Si ¿ .ïï g "S M cn^ Q)

- Page 603 and 604:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa of

- Page 605 and 606:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa for

- Page 607 and 608:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa mil

- Page 609 and 610:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa of

- Page 611 and 612:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa The

- Page 613 and 614:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa as

- Page 615 and 616:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa is

- Page 617 and 618:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa ore

- Page 619 and 620:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Nil

- Page 621 and 622:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa the

- Page 623 and 624:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa The

- Page 625:

f^\ < J\ ¿tí \ LJ C-«-3 } r / *

- Page 629 and 630:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa cha

- Page 631 and 632:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Ear

- Page 633 and 634:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa The

- Page 635 and 636:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa pro

- Page 637 and 638:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa is

- Page 639 and 640:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa sit

- Page 641 and 642:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa com

- Page 643 and 644:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa In

- Page 645 and 646:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa bur

- Page 647 and 648:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Exc

- Page 649 and 650:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa ind

- Page 651 and 652:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa of

- Page 653 and 654:

Central Africa 5 F. VAN NOTEN with

- Page 655 and 656:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa The

- Page 657 and 658:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa wer

- Page 659:

§ e B Aï S1- 626

- Page 663 and 664:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa But

- Page 665 and 666:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa mos

- Page 667 and 668:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Mor

- Page 669 and 670:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa The

- Page 671 and 672:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Exc

- Page 673 and 674:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Rec

- Page 675 and 676:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa sur

- Page 677 and 678:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa sig

- Page 679 and 680:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa of

- Page 681 and 682:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa FIG

- Page 683 and 684:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Whi

- Page 685 and 686:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa The

- Page 687 and 688:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Ms,

- Page 689 and 690:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa cou

- Page 691 and 692:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa fig

- Page 693 and 694:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa of

- Page 696 and 697:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa APP

- Page 698 and 699:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa

- Page 700 and 701:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa rem

- Page 702 and 703:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa FIG

- Page 704 and 705:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa FIG

- Page 706 and 707:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa clo

- Page 708:

672

- Page 712 and 713:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa dis

- Page 714 and 715:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa fro

- Page 716 and 717:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa It

- Page 718 and 719:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Bul

- Page 720 and 721:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa in

- Page 722 and 723:

Ancient Civilisations of Africa in

- Page 725 and 726:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa whe

- Page 728 and 729:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Cop

- Page 730 and 731:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa occ

- Page 732 and 733:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa rec

- Page 734 and 735:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa J\C

- Page 736 and 737:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa FIG

- Page 738 and 739:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa how

- Page 740 and 741:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa and

- Page 742 and 743:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa The

- Page 744 and 745:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa at

- Page 746 and 747:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa sou

- Page 748 and 749:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa of

- Page 750 and 751:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa col

- Page 752 and 753:

a 0 2 4 6 8cm 1 I I « 0 1 2 3cm i

- Page 754 and 755:

plate 28.1 Stone pot, Vohemar civil

- Page 756 and 757:

plate 28.7 Terraced rice fields nea

- Page 758 and 759:

The societies of Africa south of th

- Page 760 and 761:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Akj

- Page 762 and 763:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa was

- Page 764 and 765:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa fea

- Page 766 and 767:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa of

- Page 768 and 769:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa whe

- Page 770 and 771:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa dep

- Page 772 and 773:

Conclusion G. MOKHTAR In this volum

- Page 774 and 775:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa the

- Page 776 and 777:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa tha

- Page 778 and 779:

Members of the International Scient

- Page 780 and 781:

Biographies of Authors INTRODUCTION

- Page 782 and 783:

Bibliography The publishers wish to

- Page 784 and 785:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa CC

- Page 786 and 787:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa UJ

- Page 788 and 789:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Car

- Page 790 and 791:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Bor

- Page 792 and 793:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Car

- Page 794 and 795:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Con

- Page 796 and 797:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Deg

- Page 798 and 799:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Du

- Page 800 and 801:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Fé

- Page 802 and 803:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Goy

- Page 804 and 805:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Heu

- Page 806 and 807:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Jen

- Page 808 and 809:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Lan

- Page 810 and 811:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Mac

- Page 812 and 813:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Mic

- Page 814 and 815:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Oli

- Page 816 and 817:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Por

- Page 818 and 819:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Res

- Page 820 and 821:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Sch

- Page 822 and 823:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Ste

- Page 824 and 825:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Vin

- Page 826 and 827:

Subject Index Acheulean period, 67

- Page 828 and 829:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Kus

- Page 830 and 831:

Index of Persons Abale, 282 Abar, 3

- Page 832 and 833:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Hek

- Page 834 and 835:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Str

- Page 836 and 837:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Car

- Page 838 and 839:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Kah

- Page 840 and 841:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Pha

- Page 842 and 843:

Index of Ethnonyms Abyssinians, 385

- Page 844:

Ancient Civilizations of Africa Tou