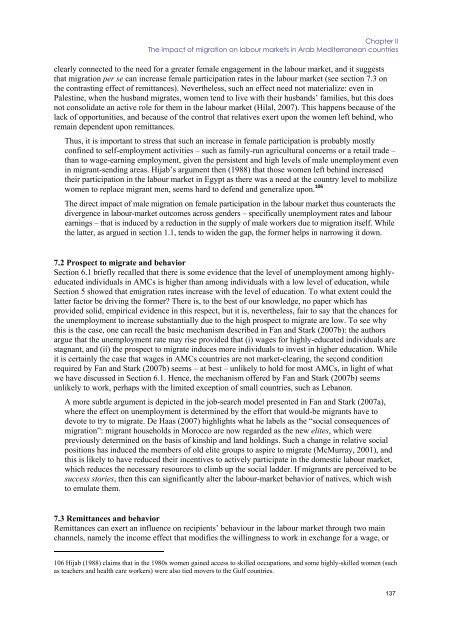

<strong>European</strong> CommissionOccasional Paper 60, Volume Iactivity in Egypt (Assad et al., 2007), thus reducing the probability that this child is fruitfullyattending school. 1046.5 Social remittances <strong>and</strong> labour forceThe contribution by Fargues (2007b) demonstrates that the transfer of ideas that occurs because of<strong>migration</strong> can substantially influence the labour <strong>market</strong>s of AMCs through its effect on demographicchoices; Fargues’ (2007b) idea is that the level of fertility in destination countries influences the levelthat prevails origin countries. Such an argument means that this effect is uneven across AMC countriesbecause – as section 5 showed – these countries greatly differ in the geographical distribution of theirmigrants. Migrants from the Maghreb predominantly move towards countries with a low level offertility – <strong>and</strong> higher rates of female participation on labour <strong>market</strong>s, see section 7.4 – while migrantsfrom the Mashreq move towards countries with higher levels of fertility, <strong>and</strong> more conservative socialstructures. Thus, while past <strong>migration</strong> <strong>flows</strong> are indirectly contributing to alleviate the current pressureon labour <strong>market</strong>s in Maghreb countries via a reduction in the size of younger cohorts in thepopulation, the opposite occurs in the Mashreq countries. This means that social remittances can eitherreinforce or dampen the effect of actual <strong>migration</strong>, as described in section 6.1.As far as the impact of <strong>migration</strong> on skill acquisition is concerned, Fargues (2008b) observes that“a shift from a remittances-driven to a human-capital-driven pattern of <strong>migration</strong> is underway” forAMCs, meaning that the decision to migrate is no longer solely driven by the willingness to sendremittances back home, but also by the desire to make an adequate use of would-be migrants’human capital. Fargues (2008b) also adds that “today the links MENA states establish with theirDiasporas are aimed at maximizing remittances <strong>and</strong> economic investments in the home country.Tomorrow, states will have to channel the diaspora’s knowledge <strong>and</strong> skills. For that purpose, theywill have to [create an environment] favourable to <strong>flows</strong> of ideas <strong>and</strong> knowledge”, emphasizing thekey role of social remittances in shaping the impact of <strong>migration</strong> upon AMCs (see section 9.3).7. Behaviour on the labour <strong>market</strong>7.1 Actual <strong>migration</strong> <strong>and</strong> behaviourMigration can exert a direct impact on the labour-<strong>market</strong> participation of stayers when migrants comefrom households which earn their livelihood from family-run economic activities, such as small-scaleagricultural concerns. As we have seen in section 2.1, the migrant is often the main breadwinnerwithin the household, <strong>and</strong> this gives rise to the need to replace him or her in family-run activities inorder to avoid a reduction in incomes. The book by Ennaji <strong>and</strong> Sadiqi (2008) analyzes the impact ofthe – predominantly male – <strong>migration</strong> from Morocco on the women left behind, <strong>and</strong> it finds that thesewomen tend to assume roles in production activities that were formerly covered by male migrants.Nevertheless, as Ennaji <strong>and</strong> Sadiqi (2008) argue, “most migrant husb<strong>and</strong>s would refuse to allow theirwives to work outside the home because this work jeopardizes their social role <strong>and</strong> the image ashousehold bread-winners”. Ennaji <strong>and</strong> Sadiqi (2008) also provide evidence that <strong>migration</strong> is associatedwith a change in family structures, as 26.2 percent of the sampled women go back to live with theirparents, who can help them in taking care of the children. 105 Such a change in family structure is104 ILO (2002) shows how the incidence of child work in Middle East <strong>and</strong> Northern African countries st<strong>and</strong>s at 15 percent, alevel that is lower than most other developing regions, but that nevertheless suggests that child work is far from being absentthere.105 This is so because AMCs are often characterized by “weak transportation <strong>and</strong> child care infrastructure [that] discouragewomen from going out to work, as does the lack of social support for children or the aged, the burden of whose care falls onwomen” (UNDP, 2006), <strong>and</strong> the women left behind do not seek employment because of “their inability to combine theirwork outside with duties as mothers <strong>and</strong> housewives” (Ennaji <strong>and</strong> Sadiqi, 2008).136

Chapter IIThe impact of <strong>migration</strong> on labour <strong>market</strong>s in Arab Mediterranean countriesclearly connected to the need for a greater female engagement in the labour <strong>market</strong>, <strong>and</strong> it suggeststhat <strong>migration</strong> per se can increase female participation rates in the labour <strong>market</strong> (see section 7.3 onthe contrasting effect of remittances). Nevertheless, such an effect need not materialize: even inPalestine, when the husb<strong>and</strong> migrates, women tend to live with their husb<strong>and</strong>s’ families, but this doesnot consolidate an active role for them in the labour <strong>market</strong> (Hilal, 2007). This happens because of thelack of opportunities, <strong>and</strong> because of the control that relatives exert upon the women left behind, whoremain dependent upon remittances.Thus, it is important to stress that such an increase in female participation is probably mostlyconfined to self-employment activities – such as family-run agricultural concerns or a retail trade –than to wage-earning employment, given the persistent <strong>and</strong> high levels of male unemployment evenin migrant-sending areas. Hijab’s argument then (1988) that those women left behind increasedtheir participation in the labour <strong>market</strong> in Egypt as there was a need at the country level to mobilizewomen to replace migrant men, seems hard to defend <strong>and</strong> generalize upon. 106The direct impact of male <strong>migration</strong> on female participation in the labour <strong>market</strong> thus counteracts thedivergence in labour-<strong>market</strong> outcomes across genders – specifically unemployment rates <strong>and</strong> labourearnings – that is induced by a reduction in the supply of male workers due to <strong>migration</strong> itself. Whilethe latter, as argued in section 1.1, tends to widen the gap, the former helps in narrowing it down.7.2 Prospect to migrate <strong>and</strong> behaviorSection 6.1 briefly recalled that there is some evidence that the level of unemployment among highlyeducatedindividuals in AMCs is higher than among individuals with a low level of education, whileSection 5 showed that e<strong>migration</strong> rates increase with the level of education. To what extent could thelatter factor be driving the former? There is, to the best of our knowledge, no paper which hasprovided solid, empirical evidence in this respect, but it is, nevertheless, fair to say that the chances forthe unemployment to increase substantially due to the high prospect to migrate are low. To see whythis is the case, one can recall the basic mechanism described in Fan <strong>and</strong> Stark (2007b): the authorsargue that the unemployment rate may rise provided that (i) wages for highly-educated individuals arestagnant, <strong>and</strong> (ii) the prospect to migrate induces more individuals to invest in higher education. Whileit is certainly the case that wages in AMCs countries are not <strong>market</strong>-clearing, the second conditionrequired by Fan <strong>and</strong> Stark (2007b) seems – at best – unlikely to hold for most AMCs, in light of whatwe have discussed in Section 6.1. Hence, the mechanism offered by Fan <strong>and</strong> Stark (2007b) seemsunlikely to work, perhaps with the limited exception of small countries, such as Lebanon.A more subtle argument is depicted in the job-search model presented in Fan <strong>and</strong> Stark (2007a),where the effect on unemployment is determined by the effort that would-be migrants have todevote to try to migrate. De Haas (2007) highlights what he labels as the “social consequences of<strong>migration</strong>”: migrant households in Morocco are now regarded as the new elites, which werepreviously determined on the basis of kinship <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> holdings. Such a change in relative socialpositions has induced the members of old elite groups to aspire to migrate (McMurray, 2001), <strong>and</strong>this is likely to have reduced their incentives to actively participate in the domestic labour <strong>market</strong>,which reduces the necessary resources to climb up the social ladder. If migrants are perceived to besuccess stories, then this can significantly alter the labour-<strong>market</strong> behavior of natives, which wishto emulate them.7.3 Remittances <strong>and</strong> behaviorRemittances can exert an influence on recipients’ behaviour in the labour <strong>market</strong> through two mainchannels, namely the income effect that modifies the willingness to work in exchange for a wage, or106 Hijab (1988) claims that in the 1980s women gained access to skilled occupations, <strong>and</strong> some highly-skilled women (suchas teachers <strong>and</strong> health care workers) were also tied movers to the Gulf countries.137

- Page 5 and 6:

STUDYLABOUR MARKETS PERFORMANCE AND

- Page 7 and 8:

Table of ContentsLABOUR MARKETS PER

- Page 10:

8.1 Actual migration and consumptio

- Page 15 and 16:

Chapter IFinal Report 15 MILLION NE

- Page 17 and 18:

Chapter IFinal Report …so that MI

- Page 19 and 20:

Chapter IFinal Reportroots). The cu

- Page 21 and 22:

Chapter IFinal Report In AMCs, REMI

- Page 23 and 24:

Chapter IFinal Reportpolicies. This

- Page 25 and 26:

Chapter IFinal ReportMediterranean

- Page 27 and 28:

Chapter IFinal ReportMore recently,

- Page 29 and 30:

Chapter IFinal Reportfor EU employm

- Page 31 and 32:

Chapter IFinal Reportchosen, these

- Page 33 and 34:

Chapter IFinal Reportexit of women

- Page 35 and 36:

Chapter IFinal ReportFigure 1.2.1.

- Page 37 and 38:

Chapter IFinal ReportA Declining Em

- Page 39 and 40:

Chapter IFinal ReportThe same year,

- Page 41 and 42:

Chapter IFinal ReportTable 2.2.1. I

- Page 43 and 44:

Chapter IFinal Reportminimum wages

- Page 45 and 46:

Chapter IFinal Report2.4 Unemployme

- Page 47 and 48:

Chapter IFinal ReportYouth Unemploy

- Page 49 and 50:

Chapter IFinal ReportBut one should

- Page 51 and 52:

Chapter IFinal Reportmillion) 10 .

- Page 53 and 54:

Chapter IFinal Reportmight intensif

- Page 55 and 56:

Chapter IFinal Reporttrue labour ma

- Page 57 and 58:

Chapter IFinal Reportto reform the

- Page 59 and 60:

Chapter IFinal ReportFrom a differe

- Page 61 and 62:

Chapter IFinal ReportTable 4.2.1 Ou

- Page 63 and 64:

Chapter IFinal ReportSource: Adams

- Page 65 and 66:

Chapter IFinal Reportin the destina

- Page 67 and 68:

Chapter IFinal ReportIn conclusion,

- Page 69 and 70:

Chapter IFinal Reportorganised in B

- Page 71 and 72:

Chapter IFinal Reportsecond Intifad

- Page 73 and 74:

Chapter IFinal Reportstands at 29.7

- Page 75 and 76:

Chapter IFinal Reportconstruction w

- Page 77 and 78:

Chapter IFinal ReportAs far as the

- Page 79 and 80:

Chapter IFinal Reportother cases, l

- Page 81 and 82:

Chapter IFinal Reportunemployment a

- Page 83 and 84:

Chapter IFinal Reportof Egypt, so f

- Page 85 and 86:

Chapter IFinal ReportWhile progress

- Page 87 and 88: Chapter IFinal ReportThese reservat

- Page 89 and 90: Chapter IFinal ReportAs Figure 6.3.

- Page 91 and 92: Chapter IFinal Reportin skill devel

- Page 93 and 94: Chapter IFinal ReportThe Directive

- Page 95 and 96: Chapter IFinal ReportThe need for

- Page 97 and 98: Chapter IFinal Reportobjectives are

- Page 99 and 100: Chapter IFinal Reporttrue Euro-Medi

- Page 101 and 102: Chapter IFinal Report- Putting empl

- Page 103 and 104: Chapter IFinal Report promotion of

- Page 105 and 106: Chapter IFinal ReportOtherADAMS, R.

- Page 107 and 108: Chapter IFinal ReportDE BEL-AIR, F.

- Page 109 and 110: Chapter IFinal ReportGUPTA, S., C.

- Page 111 and 112: Chapter IFinal ReportOECD (2000): M

- Page 113 and 114: Chapter II - Thematic Background Pa

- Page 115 and 116: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 117 and 118: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 119 and 120: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 121 and 122: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 123 and 124: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 125 and 126: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 127 and 128: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 129 and 130: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 131 and 132: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 133 and 134: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 135 and 136: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 137: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 141 and 142: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 143 and 144: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 145 and 146: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 147 and 148: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 149 and 150: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 151 and 152: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 153 and 154: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 155 and 156: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 157 and 158: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 159 and 160: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 161 and 162: Chapter III - Thematic Background P

- Page 163 and 164: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 165 and 166: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 167 and 168: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 169 and 170: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 171 and 172: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 173 and 174: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 175 and 176: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 177 and 178: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 179 and 180: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 181 and 182: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 183 and 184: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 185 and 186: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 187 and 188: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 189 and 190:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 191 and 192:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 193 and 194:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 195 and 196:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 197 and 198:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 199 and 200:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 201 and 202:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 203 and 204:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 205 and 206:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 207:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa