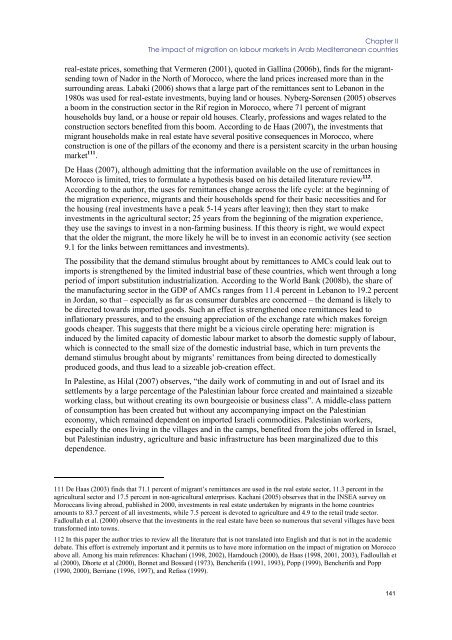

<strong>European</strong> CommissionOccasional Paper 60, Volume Iaverage age of return migrants is between 30 <strong>and</strong> 44 years (Fourati, 2008). Finally, ELMPS (2006)data shows that 35 percent of returnees in Egypt are less than 40 years old, <strong>and</strong> 35 percent arebetween 40 <strong>and</strong> 50 years old.8.3 Remittances <strong>and</strong> consumption patternsAs we argued in section 2.1, the stimulus that <strong>migration</strong> – via remittances – brings to private dem<strong>and</strong>produces substantial effects on the labour <strong>market</strong> only inasmuch as it is directed towards domesticallyproduced goods <strong>and</strong> services. Regrettably, as Gallina (2006b) observes, there is limited information onthe pattern of remittance used in AMCs countries. Some information – albeit coming from a surveywith a limited coverage – are provided by EIB (2006), which analyzed the distribution of remittancesacross alternative budget items in all AMCs but Palestine. Table 8.1 reports the main findings fromthis survey, which demonstrates that everyday expenses absorb most of the income arising fromremittances, while limited resources are devoted to investments. Schramm (2009) provides evidence –for Tunisia, Morocco <strong>and</strong> Egypt – that suggests that basic consumption needs (food, heat <strong>and</strong>clothing), absorb most remittances.DailyexpensesPaymentof schoolfeesTable 8.1. Use of remittances in AMCsBuildinga houseSettingup acompanyInvestmentsOtherNumber ofintervieweesAlgeria 45 13 23 3 5 11 64Egypt 43 12 18 - 15 12 31Jordan 74 16 4 - 6 - 40Lebanon 56 24 5 5 5 5 41Morocco 46 31 16 - 5 2 40Tunisia - 23 34 2 16 25 40Syria 61 11 8 - - 20 49Source: EIB (2006)Still, the argument that most recipient households report that daily consumption needs absorb thegreatest share of their remittance incomes does not suffice to dismiss the concern that remittancesmay fuel the dem<strong>and</strong> for imported products. 109 An interesting – although admittedly extreme – caseis represented by Algeria, where most of the remittances are transferred in kind rather than in cash,as migrants distrust the local financial system. Khachani (2004) argued that the value of goodsimported by Algerian migrants who temporarily returned home on holidays was estimated at $2.5billion per year; needless to say, such a huge amount of resources fails to generate any job-creationeffect, as they cannot be directly used for productive investments, being mostly in the form ofconsumption goods. By the same token, Nassar (2005) argues that Egyptian recipient householdsdevote a sizeable part of remittances to accumulating hoards of valuable items, such as gold <strong>and</strong>precious stones, <strong>and</strong> this dampens the ensuing stimulus on the dem<strong>and</strong> for workers. 110Real estate can also represent a sizeable store of value for recipient households: Fletcher (1999)demonstrates that in Tunisia e<strong>migration</strong> areas have experienced a remittance-induced sharp raise in109 Note that respondents to these kinds of surveys always report that remittances are earmarked for basic consumptionexpenditures, although this does not suffice to rule out – given the inherent fungibility of incomes – the possibility that theyactually lead to a significant reshaping of expenditure patterns.110 Note that such behaviour can be linked to the temporary character of remittance incomes, <strong>and</strong> to the probability that sucha flow might come to an unexpected end, because of the major fluctuations in the dem<strong>and</strong> for immigrant workers in the Gulfcountries.140

Chapter IIThe impact of <strong>migration</strong> on labour <strong>market</strong>s in Arab Mediterranean countriesreal-estate prices, something that Vermeren (2001), quoted in Gallina (2006b), finds for the migrantsendingtown of Nador in the North of Morocco, where the l<strong>and</strong> prices increased more than in thesurrounding areas. Labaki (2006) shows that a large part of the remittances sent to Lebanon in the1980s was used for real-estate investments, buying l<strong>and</strong> or houses. Nyberg-Sørensen (2005) observesa boom in the construction sector in the Rif region in Morocco, where 71 percent of migranthouseholds buy l<strong>and</strong>, or a house or repair old houses. Clearly, professions <strong>and</strong> wages related to theconstruction sectors benefited from this boom. According to de Haas (2007), the investments thatmigrant households make in real estate have several positive consequences in Morocco, whereconstruction is one of the pillars of the economy <strong>and</strong> there is a persistent scarcity in the urban housing<strong>market</strong> 111 .De Haas (2007), although admitting that the information available on the use of remittances inMorocco is limited, tries to formulate a hypothesis based on his detailed literature review 112 .According to the author, the uses for remittances change across the life cycle: at the beginning ofthe <strong>migration</strong> experience, migrants <strong>and</strong> their households spend for their basic necessities <strong>and</strong> forthe housing (real investments have a peak 5-14 years after leaving); then they start to makeinvestments in the agricultural sector; 25 years from the beginning of the <strong>migration</strong> experience,they use the savings to invest in a non-farming business. If this theory is right, we would expectthat the older the migrant, the more likely he will be to invest in an economic activity (see section9.1 for the links between remittances <strong>and</strong> investments).The possibility that the dem<strong>and</strong> stimulus brought about by remittances to AMCs could leak out toimports is strengthened by the limited industrial base of these countries, which went through a longperiod of import substitution industrialization. According to the World Bank (2008b), the share ofthe manufacturing sector in the GDP of AMCs ranges from 11.4 percent in Lebanon to 19.2 percentin Jordan, so that – especially as far as consumer durables are concerned – the dem<strong>and</strong> is likely tobe directed towards imported goods. Such an effect is strengthened once remittances lead toinflationary pressures, <strong>and</strong> to the ensuing appreciation of the exchange rate which makes foreigngoods cheaper. This suggests that there might be a vicious circle operating here: <strong>migration</strong> isinduced by the limited capacity of domestic labour <strong>market</strong> to absorb the domestic supply of labour,which is connected to the small size of the domestic industrial base, which in turn prevents thedem<strong>and</strong> stimulus brought about by migrants’ remittances from being directed to domesticallyproduced goods, <strong>and</strong> thus lead to a sizeable job-creation effect.In Palestine, as Hilal (2007) observes, “the daily work of commuting in <strong>and</strong> out of Israel <strong>and</strong> itssettlements by a large percentage of the Palestinian labour force created <strong>and</strong> maintained a sizeableworking class, but without creating its own bourgeoisie or business class”. A middle-class patternof consumption has been created but without any accompanying impact on the Palestinianeconomy, which remained dependent on imported Israeli commodities. Palestinian workers,especially the ones living in the villages <strong>and</strong> in the camps, benefited from the jobs offered in Israel,but Palestinian industry, agriculture <strong>and</strong> basic infrastructure has been marginalized due to thisdependence.111 De Haas (2003) finds that 71.1 percent of migrant’s remittances are used in the real estate sector, 11.3 percent in theagricultural sector <strong>and</strong> 17.5 percent in non-agricultural enterprises. Kachani (2005) observes that in the INSEA survey onMoroccans living abroad, published in 2000, investments in real estate undertaken by migrants in the home countriesamounts to 83.7 percent of all investments, while 7.5 percent is devoted to agriculture <strong>and</strong> 4.9 to the retail trade sector.Fadloullah et al. (2000) observe that the investments in the real estate have been so numerous that several villages have beentransformed into towns.112 In this paper the author tries to review all the literature that is not translated into English <strong>and</strong> that is not in the academicdebate. This effort is extremely important <strong>and</strong> it permits us to have more information on the impact of <strong>migration</strong> on Moroccoabove all. Among his main references: Khachani (1998, 2002), Hamdouch (2000), de Haas (1998, 2001, 2003), Fadloullah etal (2000), Dhorte et al (2000), Bonnet <strong>and</strong> Bossard (1973), Bencherifa (1991, 1993), Popp (1999), Bencherifa <strong>and</strong> Popp(1990, 2000), Berriane (1996, 1997), <strong>and</strong> Refass (1999).141

- Page 5 and 6:

STUDYLABOUR MARKETS PERFORMANCE AND

- Page 7 and 8:

Table of ContentsLABOUR MARKETS PER

- Page 10:

8.1 Actual migration and consumptio

- Page 15 and 16:

Chapter IFinal Report 15 MILLION NE

- Page 17 and 18:

Chapter IFinal Report …so that MI

- Page 19 and 20:

Chapter IFinal Reportroots). The cu

- Page 21 and 22:

Chapter IFinal Report In AMCs, REMI

- Page 23 and 24:

Chapter IFinal Reportpolicies. This

- Page 25 and 26:

Chapter IFinal ReportMediterranean

- Page 27 and 28:

Chapter IFinal ReportMore recently,

- Page 29 and 30:

Chapter IFinal Reportfor EU employm

- Page 31 and 32:

Chapter IFinal Reportchosen, these

- Page 33 and 34:

Chapter IFinal Reportexit of women

- Page 35 and 36:

Chapter IFinal ReportFigure 1.2.1.

- Page 37 and 38:

Chapter IFinal ReportA Declining Em

- Page 39 and 40:

Chapter IFinal ReportThe same year,

- Page 41 and 42:

Chapter IFinal ReportTable 2.2.1. I

- Page 43 and 44:

Chapter IFinal Reportminimum wages

- Page 45 and 46:

Chapter IFinal Report2.4 Unemployme

- Page 47 and 48:

Chapter IFinal ReportYouth Unemploy

- Page 49 and 50:

Chapter IFinal ReportBut one should

- Page 51 and 52:

Chapter IFinal Reportmillion) 10 .

- Page 53 and 54:

Chapter IFinal Reportmight intensif

- Page 55 and 56:

Chapter IFinal Reporttrue labour ma

- Page 57 and 58:

Chapter IFinal Reportto reform the

- Page 59 and 60:

Chapter IFinal ReportFrom a differe

- Page 61 and 62:

Chapter IFinal ReportTable 4.2.1 Ou

- Page 63 and 64:

Chapter IFinal ReportSource: Adams

- Page 65 and 66:

Chapter IFinal Reportin the destina

- Page 67 and 68:

Chapter IFinal ReportIn conclusion,

- Page 69 and 70:

Chapter IFinal Reportorganised in B

- Page 71 and 72:

Chapter IFinal Reportsecond Intifad

- Page 73 and 74:

Chapter IFinal Reportstands at 29.7

- Page 75 and 76:

Chapter IFinal Reportconstruction w

- Page 77 and 78:

Chapter IFinal ReportAs far as the

- Page 79 and 80:

Chapter IFinal Reportother cases, l

- Page 81 and 82:

Chapter IFinal Reportunemployment a

- Page 83 and 84:

Chapter IFinal Reportof Egypt, so f

- Page 85 and 86:

Chapter IFinal ReportWhile progress

- Page 87 and 88:

Chapter IFinal ReportThese reservat

- Page 89 and 90:

Chapter IFinal ReportAs Figure 6.3.

- Page 91 and 92: Chapter IFinal Reportin skill devel

- Page 93 and 94: Chapter IFinal ReportThe Directive

- Page 95 and 96: Chapter IFinal ReportThe need for

- Page 97 and 98: Chapter IFinal Reportobjectives are

- Page 99 and 100: Chapter IFinal Reporttrue Euro-Medi

- Page 101 and 102: Chapter IFinal Report- Putting empl

- Page 103 and 104: Chapter IFinal Report promotion of

- Page 105 and 106: Chapter IFinal ReportOtherADAMS, R.

- Page 107 and 108: Chapter IFinal ReportDE BEL-AIR, F.

- Page 109 and 110: Chapter IFinal ReportGUPTA, S., C.

- Page 111 and 112: Chapter IFinal ReportOECD (2000): M

- Page 113 and 114: Chapter II - Thematic Background Pa

- Page 115 and 116: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 117 and 118: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 119 and 120: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 121 and 122: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 123 and 124: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 125 and 126: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 127 and 128: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 129 and 130: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 131 and 132: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 133 and 134: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 135 and 136: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 137 and 138: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 139 and 140: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 141: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 145 and 146: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 147 and 148: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 149 and 150: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 151 and 152: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 153 and 154: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 155 and 156: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 157 and 158: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 159 and 160: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 161 and 162: Chapter III - Thematic Background P

- Page 163 and 164: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 165 and 166: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 167 and 168: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 169 and 170: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 171 and 172: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 173 and 174: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 175 and 176: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 177 and 178: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 179 and 180: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 181 and 182: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 183 and 184: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 185 and 186: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 187 and 188: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 189 and 190: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 191 and 192: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 193 and 194:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 195 and 196:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 197 and 198:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 199 and 200:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 201 and 202:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 203 and 204:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 205 and 206:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 207:

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa