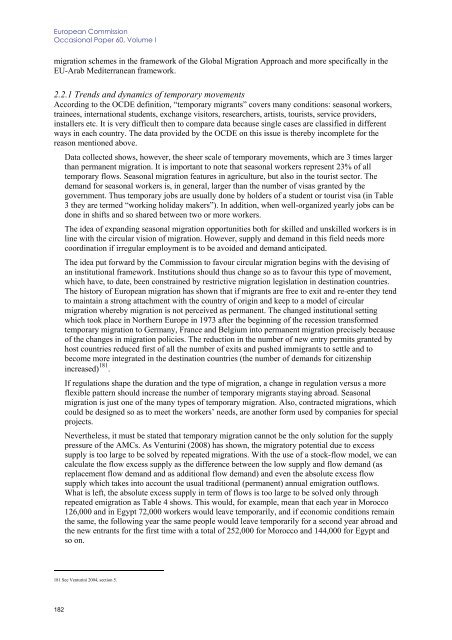

<strong>European</strong> CommissionOccasional Paper 60, Volume I<strong>migration</strong> schemes in the framework of the Global Migration Approach <strong>and</strong> more specifically in theEU-Arab Mediterranean framework.2.2.1 Trends <strong>and</strong> dynamics of temporary movementsAccording to the OCDE definition, “temporary migrants” covers many conditions: seasonal workers,trainees, international students, exchange visitors, researchers, artists, tourists, service providers,installers etc. It is very difficult then to compare data because single cases are classified in differentways in each country. The data provided by the OCDE on this issue is thereby incomplete for thereason mentioned above.Data collected shows, however, the sheer scale of temporary movements, which are 3 times largerthan permanent <strong>migration</strong>. It is important to note that seasonal workers represent 23% of alltemporary <strong>flows</strong>. Seasonal <strong>migration</strong> features in agriculture, but also in the tourist sector. Thedem<strong>and</strong> for seasonal workers is, in general, larger than the number of visas granted by thegovernment. Thus temporary jobs are usually done by holders of a student or tourist visa (in Table3 they are termed “working holiday makers”). In addition, when well-organized yearly jobs can bedone in shifts <strong>and</strong> so shared between two or more workers.The idea of exp<strong>and</strong>ing seasonal <strong>migration</strong> opportunities both for skilled <strong>and</strong> unskilled workers is inline with the circular vision of <strong>migration</strong>. However, supply <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> in this field needs morecoordination if irregular employment is to be avoided <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> anticipated.The idea put forward by the Commission to favour circular <strong>migration</strong> begins with the devising ofan institutional framework. Institutions should thus change so as to favour this type of movement,which have, to date, been constrained by restrictive <strong>migration</strong> legislation in destination countries.The history of <strong>European</strong> <strong>migration</strong> has shown that if migrants are free to exit <strong>and</strong> re-enter they tendto maintain a strong attachment with the country of origin <strong>and</strong> keep to a model of circular<strong>migration</strong> whereby <strong>migration</strong> is not perceived as permanent. The changed institutional settingwhich took place in Northern Europe in 1973 after the beginning of the recession transformedtemporary <strong>migration</strong> to Germany, France <strong>and</strong> Belgium into permanent <strong>migration</strong> precisely becauseof the changes in <strong>migration</strong> policies. The reduction in the number of new entry permits granted byhost countries reduced first of all the number of exits <strong>and</strong> pushed immigrants to settle <strong>and</strong> tobecome more integrated in the destination countries (the number of dem<strong>and</strong>s for citizenshipincreased) 181 .If regulations shape the duration <strong>and</strong> the type of <strong>migration</strong>, a change in regulation versus a moreflexible pattern should increase the number of temporary migrants staying abroad. Seasonal<strong>migration</strong> is just one of the many types of temporary <strong>migration</strong>. Also, contracted <strong>migration</strong>s, whichcould be designed so as to meet the workers’ needs, are another form used by companies for specialprojects.Nevertheless, it must be stated that temporary <strong>migration</strong> cannot be the only solution for the supplypressure of the AMCs. As Venturini (2008) has shown, the migratory potential due to excesssupply is too large to be solved by repeated <strong>migration</strong>s. With the use of a stock-flow model, we cancalculate the flow excess supply as the difference between the low supply <strong>and</strong> flow dem<strong>and</strong> (asreplacement flow dem<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> as additional flow dem<strong>and</strong>) <strong>and</strong> even the absolute excess <strong>flows</strong>upply which takes into account the usual traditional (permanent) annual e<strong>migration</strong> out<strong>flows</strong>.What is left, the absolute excess supply in term of <strong>flows</strong> is too large to be solved only throughrepeated e<strong>migration</strong> as Table 4 shows. This would, for example, mean that each year in Morocco126,000 <strong>and</strong> in Egypt 72,000 workers would leave temporarily, <strong>and</strong> if economic conditions remainthe same, the following year the same people would leave temporarily for a second year abroad <strong>and</strong>the new entrants for the first time with a total of 252,000 for Morocco <strong>and</strong> 144,000 for Egypt <strong>and</strong>so on.181 See Venturini 2004, section 5.182

Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towards Arab Mediterranean Countries <strong>and</strong> its Impact on their <strong>Labour</strong> MarketsTable 3 In<strong>flows</strong> of temporary labour migrants, selected OECD countries, 2003-2006Thous<strong>and</strong>s2003 2004 2005 2006Distribution(2006)Working holiday makers 442 463 497 536 21Trainees 146 147 161 182 7Seasonal workers 545 568 571 576 23Intra-company transfers 89 89 87 99 4Other temporary workers 958 1,093 1,085 1,105 44All categories 2,180 2,360 2,401 2,498 100Per 1 000population (2006)Australia 152 159 183 219 10,7Austria 30 27 15 4 0,5Belgium 2 31 33 42 4,0Bulgaria - 1 1 1 0,1Canada 118 124 133 146 4,5Denmark 5 5 5 6 1,1France 26 26 27 28 0,5Germany 446 440 415 379 4,6Italy 69 70 85 98 1,7Japan 217 231 202 164 1,3Korea 75 65 73 86 1,8Mexico 45 42 46 40 0,4Netherl<strong>and</strong>s 43 52 56 83 5,1New Zeal<strong>and</strong> 65 70 78 87 21,1Norway 21 28 22 38 8,2Portugal 3 13 8 7 0,7Sweden 8 9 7 7 0,8Switzerl<strong>and</strong> 142 116 104 117 15,7United Kingdom 137 239 275 266 4,4United States 577 612 635 678 2,3All countries 2,180 2,360 2,401 2,498 2,6Annual change (%) na 8,3 1,7 4,0Statlink http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/427045515037Source: OECD database on International Migration183

- Page 5 and 6:

STUDYLABOUR MARKETS PERFORMANCE AND

- Page 7 and 8:

Table of ContentsLABOUR MARKETS PER

- Page 10:

8.1 Actual migration and consumptio

- Page 15 and 16:

Chapter IFinal Report 15 MILLION NE

- Page 17 and 18:

Chapter IFinal Report …so that MI

- Page 19 and 20:

Chapter IFinal Reportroots). The cu

- Page 21 and 22:

Chapter IFinal Report In AMCs, REMI

- Page 23 and 24:

Chapter IFinal Reportpolicies. This

- Page 25 and 26:

Chapter IFinal ReportMediterranean

- Page 27 and 28:

Chapter IFinal ReportMore recently,

- Page 29 and 30:

Chapter IFinal Reportfor EU employm

- Page 31 and 32:

Chapter IFinal Reportchosen, these

- Page 33 and 34:

Chapter IFinal Reportexit of women

- Page 35 and 36:

Chapter IFinal ReportFigure 1.2.1.

- Page 37 and 38:

Chapter IFinal ReportA Declining Em

- Page 39 and 40:

Chapter IFinal ReportThe same year,

- Page 41 and 42:

Chapter IFinal ReportTable 2.2.1. I

- Page 43 and 44:

Chapter IFinal Reportminimum wages

- Page 45 and 46:

Chapter IFinal Report2.4 Unemployme

- Page 47 and 48:

Chapter IFinal ReportYouth Unemploy

- Page 49 and 50:

Chapter IFinal ReportBut one should

- Page 51 and 52:

Chapter IFinal Reportmillion) 10 .

- Page 53 and 54:

Chapter IFinal Reportmight intensif

- Page 55 and 56:

Chapter IFinal Reporttrue labour ma

- Page 57 and 58:

Chapter IFinal Reportto reform the

- Page 59 and 60:

Chapter IFinal ReportFrom a differe

- Page 61 and 62:

Chapter IFinal ReportTable 4.2.1 Ou

- Page 63 and 64:

Chapter IFinal ReportSource: Adams

- Page 65 and 66:

Chapter IFinal Reportin the destina

- Page 67 and 68:

Chapter IFinal ReportIn conclusion,

- Page 69 and 70:

Chapter IFinal Reportorganised in B

- Page 71 and 72:

Chapter IFinal Reportsecond Intifad

- Page 73 and 74:

Chapter IFinal Reportstands at 29.7

- Page 75 and 76:

Chapter IFinal Reportconstruction w

- Page 77 and 78:

Chapter IFinal ReportAs far as the

- Page 79 and 80:

Chapter IFinal Reportother cases, l

- Page 81 and 82:

Chapter IFinal Reportunemployment a

- Page 83 and 84:

Chapter IFinal Reportof Egypt, so f

- Page 85 and 86:

Chapter IFinal ReportWhile progress

- Page 87 and 88:

Chapter IFinal ReportThese reservat

- Page 89 and 90:

Chapter IFinal ReportAs Figure 6.3.

- Page 91 and 92:

Chapter IFinal Reportin skill devel

- Page 93 and 94:

Chapter IFinal ReportThe Directive

- Page 95 and 96:

Chapter IFinal ReportThe need for

- Page 97 and 98:

Chapter IFinal Reportobjectives are

- Page 99 and 100:

Chapter IFinal Reporttrue Euro-Medi

- Page 101 and 102:

Chapter IFinal Report- Putting empl

- Page 103 and 104:

Chapter IFinal Report promotion of

- Page 105 and 106:

Chapter IFinal ReportOtherADAMS, R.

- Page 107 and 108:

Chapter IFinal ReportDE BEL-AIR, F.

- Page 109 and 110:

Chapter IFinal ReportGUPTA, S., C.

- Page 111 and 112:

Chapter IFinal ReportOECD (2000): M

- Page 113 and 114:

Chapter II - Thematic Background Pa

- Page 115 and 116:

Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 117 and 118:

Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 119 and 120:

Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 121 and 122:

Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 123 and 124:

Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 125 and 126:

Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 127 and 128:

Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 129 and 130:

Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 131 and 132:

Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 133 and 134: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 135 and 136: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 137 and 138: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 139 and 140: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 141 and 142: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 143 and 144: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 145 and 146: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 147 and 148: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 149 and 150: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 151 and 152: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 153 and 154: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 155 and 156: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 157 and 158: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 159 and 160: Chapter IIThe impact of migration o

- Page 161 and 162: Chapter III - Thematic Background P

- Page 163 and 164: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 165 and 166: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 167 and 168: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 169 and 170: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 171 and 172: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 173 and 174: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 175 and 176: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 177 and 178: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 179 and 180: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 181 and 182: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 183: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 187 and 188: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 189 and 190: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 191 and 192: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 193 and 194: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 195 and 196: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 197 and 198: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 199 and 200: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 201 and 202: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 203 and 204: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 205 and 206: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa

- Page 207: Chapter IIIEU Migration Policy towa