Download the file - United Nations Rule of Law

Download the file - United Nations Rule of Law

Download the file - United Nations Rule of Law

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

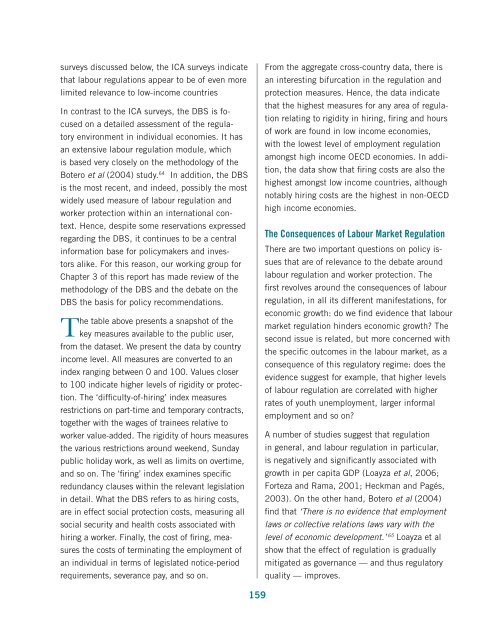

surveys discussed below, <strong>the</strong> ICA surveys indicatethat labour regulations appear to be <strong>of</strong> even morelimited relevance to low-income countriesIn contrast to <strong>the</strong> ICA surveys, <strong>the</strong> DBS is focusedon a detailed assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> regulatoryenvironment in individual economies. It hasan extensive labour regulation module, whichis based very closely on <strong>the</strong> methodology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Botero et al (2004) study. 64 In addition, <strong>the</strong> DBSis <strong>the</strong> most recent, and indeed, possibly <strong>the</strong> mostwidely used measure <strong>of</strong> labour regulation andworker protection within an international context.Hence, despite some reservations expressedregarding <strong>the</strong> DBS, it continues to be a centralinformation base for policymakers and investorsalike. For this reason, our working group forChapter 3 <strong>of</strong> this report has made review <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>methodology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> DBS and <strong>the</strong> debate on <strong>the</strong>DBS <strong>the</strong> basis for policy recommendations.The table above presents a snapshot <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>key measures available to <strong>the</strong> public user,from <strong>the</strong> dataset. We present <strong>the</strong> data by countryincome level. All measures are converted to anindex ranging between 0 and 100. Values closerto 100 indicate higher levels <strong>of</strong> rigidity or protection.The ‘difficulty-<strong>of</strong>-hiring’ index measuresrestrictions on part-time and temporary contracts,toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> wages <strong>of</strong> trainees relative toworker value-added. The rigidity <strong>of</strong> hours measures<strong>the</strong> various restrictions around weekend, Sundaypublic holiday work, as well as limits on overtime,and so on. The ‘firing’ index examines specificredundancy clauses within <strong>the</strong> relevant legislationin detail. What <strong>the</strong> DBS refers to as hiring costs,are in effect social protection costs, measuring allsocial security and health costs associated withhiring a worker. Finally, <strong>the</strong> cost <strong>of</strong> firing, measures<strong>the</strong> costs <strong>of</strong> terminating <strong>the</strong> employment <strong>of</strong>an individual in terms <strong>of</strong> legislated notice-periodrequirements, severance pay, and so on.From <strong>the</strong> aggregate cross-country data, <strong>the</strong>re isan interesting bifurcation in <strong>the</strong> regulation andprotection measures. Hence, <strong>the</strong> data indicatethat <strong>the</strong> highest measures for any area <strong>of</strong> regulationrelating to rigidity in hiring, firing and hours<strong>of</strong> work are found in low income economies,with <strong>the</strong> lowest level <strong>of</strong> employment regulationamongst high income OECD economies. In addition,<strong>the</strong> data show that firing costs are also <strong>the</strong>highest amongst low income countries, althoughnotably hiring costs are <strong>the</strong> highest in non-OECDhigh income economies.The Consequences <strong>of</strong> Labour Market RegulationThere are two important questions on policy issuesthat are <strong>of</strong> relevance to <strong>the</strong> debate aroundlabour regulation and worker protection. Thefirst revolves around <strong>the</strong> consequences <strong>of</strong> labourregulation, in all its different manifestations, foreconomic growth: do we find evidence that labourmarket regulation hinders economic growth? Thesecond issue is related, but more concerned with<strong>the</strong> specific outcomes in <strong>the</strong> labour market, as aconsequence <strong>of</strong> this regulatory regime: does <strong>the</strong>evidence suggest for example, that higher levels<strong>of</strong> labour regulation are correlated with higherrates <strong>of</strong> youth unemployment, larger informalemployment and so on?A number <strong>of</strong> studies suggest that regulationin general, and labour regulation in particular,is negatively and significantly associated withgrowth in per capita GDP (Loayza et al, 2006;Forteza and Rama, 2001; Heckman and Pagés,2003). On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, Botero et al (2004)find that ‘There is no evidence that employmentlaws or collective relations laws vary with <strong>the</strong>level <strong>of</strong> economic development.’ 65 Loayza et alshow that <strong>the</strong> effect <strong>of</strong> regulation is graduallymitigated as governance — and thus regulatoryquality — improves.159