- Page 3 and 4:

Educação para a arte Arte para a

- Page 5:

Educação para a arte Arte para a

- Page 9:

Pedagogia do grão: formação, col

- Page 13 and 14:

* Artista, pedagogo e curador, Luis

- Page 15 and 16:

câmbio de premissas. Mais do que f

- Page 17 and 18:

dados históricos, propondo a obra

- Page 19 and 20:

go de leitura bastante complexo, um

- Page 21 and 22:

nhecimentos. O fato é que é neces

- Page 23 and 24:

No primeiro assunto, esperamos cont

- Page 25 and 26:

3 Santiago Eraso, “El maestro ign

- Page 27 and 28:

entusiasmo, contradisse meu sentido

- Page 29 and 30:

* Crítico e curador independente,

- Page 31 and 32:

Esse ambiente cultural, combinado

- Page 33 and 34:

menos de 20 anos, mas surpreendente

- Page 35 and 36:

maneira autêntica. Cursos no estil

- Page 37 and 38:

enfatiza a noção de “sucesso”

- Page 39 and 40:

anônimo que espera para ser libert

- Page 41 and 42:

* Artista plástico. Participou de

- Page 43 and 44:

1 Em inglês, audience. N.T. As bie

- Page 45 and 46:

alguns dos poucos lugares onde se e

- Page 47 and 48:

sem valer. Eu diria que a possibili

- Page 49 and 50:

* Artista e professor de Artes na P

- Page 51 and 52:

de primeira mão, e a pesquisa em l

- Page 53 and 54:

fazenda de oito hectares situada no

- Page 55 and 56:

ma de um prédio autossustentável,

- Page 57 and 58:

Walter Passei dois anos fora, entre

- Page 59 and 60:

Aprendendo a amar-se mais Em 2002,

- Page 61 and 62:

tos e também a organizar os seus d

- Page 63 and 64:

Basicamente, o que eu estou tentand

- Page 65 and 66:

iniciar esta conversa, considero im

- Page 67 and 68:

2 Citação de edição francesa da

- Page 69 and 70:

simplesmente obras prontas e trabal

- Page 71 and 72:

4 Bertold Brecht (1898- 1956), poet

- Page 73 and 74:

como seres integrados e, principalm

- Page 75 and 76:

mentar que o termo “espaço públ

- Page 77 and 78:

1 Frazer Ward, ‘The Haunted Museu

- Page 79 and 80:

de poder e conhecimento através do

- Page 81 and 82:

um falso problema. A política não

- Page 83 and 84:

coordenadas de desterritorializaç

- Page 85 and 86:

5 Cornelius Castoriadis, World in F

- Page 87 and 88:

Em termos de produção de exposiç

- Page 89 and 90:

* Graduado em letras e filosofia. D

- Page 91 and 92:

4 Friederich Engels: La situación

- Page 93 and 94:

to, para a invenção de todo tipo

- Page 95 and 96:

9 Arantxa Rodriguez: “Nuevas pol

- Page 97 and 98:

14 Luc Boltanski/Eve Chiapelle: El

- Page 99 and 100:

15 e-sevilla.org: Plataforma para l

- Page 101 and 102:

17 Juan Luís Moraza: Incógnitas (

- Page 103 and 104:

ativos - que permitem reinterpretar

- Page 105 and 106:

temporário do modelo bienal, não

- Page 107 and 108:

plexidade da obra. Para dar um exem

- Page 109 and 110:

um novo trabalho, negociando entre

- Page 111 and 112:

1 Texto do website, Isuma Igloolik

- Page 113 and 114:

ecentemente, abaixo do nível do ma

- Page 115 and 116:

3 Jeanne van Heeswijk e Herve Parap

- Page 117 and 118:

5 It Can Change, texto do projeto,

- Page 119 and 120:

consumida a partir de diversos pont

- Page 121 and 122:

6 Alguns pensamentos meus sobre o p

- Page 123 and 124:

* Doutor em Educação e Professor

- Page 125 and 126:

Se considerarmos que a modernidade

- Page 127 and 128:

Essa ideia de que a verdade sobre o

- Page 129 and 130:

de, só funciona porque cada indiv

- Page 131 and 132:

estaurasse o sentido da comunidade,

- Page 133 and 134:

como uma espécie de vontade social

- Page 135 and 136:

E, dessa maneira, “se a pluralida

- Page 137 and 138:

Bibliografia BARCELONA, Pietro. Pos

- Page 139 and 140:

dade de um fenômeno que chamamos l

- Page 141 and 142:

trico e chega nos povoados, nas cid

- Page 143 and 144:

em diversos formatos segundo as car

- Page 145 and 146:

capacidades criativas. Esses meios

- Page 147 and 148:

metafórico em mim. A que quero apo

- Page 149 and 150:

e criou a mulher da costela do Adã

- Page 151 and 152:

tende rapidamente a proposta, a den

- Page 153 and 154:

Espaços em processo de construçã

- Page 155 and 156:

Nesse 31 de agosto de 1991, estáva

- Page 157 and 158:

aquilo que remete à complexidade d

- Page 159 and 160:

A linguagem Entendemos a linguagem

- Page 161 and 162:

a próxima em via ovni. Diego, o lo

- Page 163 and 164:

discursos para depois fazer que o

- Page 165 and 166:

parece ser que dar aos outros é um

- Page 167 and 168:

evitar o prazer mórbido e a captur

- Page 169 and 170:

fragmento sonoro foi o de indagar a

- Page 171:

Criança: — Não, mais nada. Prof

- Page 175 and 176:

El año 2007 representó un importa

- Page 177 and 178:

Introducción Luis Camnitzer En alg

- Page 179 and 180:

apreciación del arte? ¿Cómo se p

- Page 181 and 182:

alumnos que hagan algo que consider

- Page 183 and 184:

describimos este proyecto, siempre

- Page 185 and 186:

damental de la Secretaría Municipa

- Page 187 and 188:

Arte y educación Bruce Ferguson Es

- Page 189 and 190:

discusión de mis observaciones sob

- Page 191 and 192:

interdisciplinario es difícil y co

- Page 193 and 194:

puede hacer es promover las mejores

- Page 195 and 196:

común. (Hannah Arendt, 1977 p. 196

- Page 197 and 198:

Para aclararlo mejor, el arte tiene

- Page 199 and 200:

dades locales cancelaron abruptamen

- Page 201 and 202:

Algunas ideas sobre Arte y Educaci

- Page 203 and 204:

co-escrito un importante libro sobr

- Page 205 and 206:

niños. Uno de mis escritores prefe

- Page 207 and 208:

para conseguir una presentación en

- Page 209 and 210:

la calidad de los eventos que organ

- Page 211 and 212:

En la mesa de apertura los particip

- Page 213 and 214:

alfabetización, desde una perspect

- Page 215 and 216:

mite reflexionar, experimentar, ni

- Page 217 and 218:

Sobre la Producción de Públicos o

- Page 219 and 220:

privado (la familia, la casa, la pr

- Page 221 and 222:

co espectador, un grupo, alguien qu

- Page 223 and 224:

construcción imaginaria y profesio

- Page 225 and 226:

tampoco exclusivamente en la llamad

- Page 227 and 228:

Texto/Contexto. Tejido/Redes. Santi

- Page 229 and 230:

la utilización “sin compromiso

- Page 231 and 232:

política urbanística se ha articu

- Page 233 and 234:

encuentra el artista cuando se ve a

- Page 235 and 236:

los eventuales efectos secundarios

- Page 237 and 238:

Público para el arte/ Arte para el

- Page 239 and 240:

“Treasure Hunt” o “búsqueda

- Page 241 and 242:

Ideas para el archipiélago Ted Pur

- Page 243 and 244:

Allí habrá tiendas, bancos y una

- Page 245 and 246:

Toda investigación que produce se

- Page 247 and 248:

cosas en común, pero en su base ca

- Page 249 and 250:

1 Texto de la página web, Isuma Ig

- Page 251 and 252:

inundan su camino” (Bauman, 2001:

- Page 253 and 254:

pluralismo de sentidos, nos vemos t

- Page 255 and 256:

interés público. Se desintegraron

- Page 257 and 258:

que lo más importante para cada un

- Page 259 and 260:

tanto de su incompatibilidad. Si in

- Page 261 and 262:

al aire en directo a través de la

- Page 263 and 264:

acontecer en ese espacio interstici

- Page 265 and 266:

a lo humano de su ropaje, desnudand

- Page 267 and 268:

costillas de…” cuando alguien s

- Page 269 and 270:

Era muy interesante el hecho de la

- Page 271 and 272:

en Marte que la Tierra está mal po

- Page 273 and 274:

palabra, sino como posible efecto d

- Page 275 and 276:

Sube la música Dr. Valle: —Yo di

- Page 277 and 278:

salud en términos de “ayudar a r

- Page 279 and 280:

un taller de charla y reflexión qu

- Page 281:

Biografías Luis Camnitzer Artista,

- Page 285 and 286:

2007 represented an important step

- Page 287 and 288:

Introduction Luis Camnitzer At some

- Page 289 and 290: simultaneously when the artist gene

- Page 291 and 292: curatorial exercise, a small beginn

- Page 293 and 294: time for imagining and fantasising

- Page 295 and 296: He tries to reposition the public i

- Page 297 and 298: Art Education Bruce Ferguson It is

- Page 299 and 300: from a belief in text and language

- Page 301 and 302: fiscal planning, the mastery of int

- Page 303 and 304: e measurable. It is the text attach

- Page 305 and 306: From exhibition to school, notes fr

- Page 307 and 308: point out some possible models and

- Page 309 and 310: efusing easy conventions you have m

- Page 311 and 312: Sometimes I wind up working with th

- Page 313 and 314: practice I mean the dominate way of

- Page 315 and 316: Cleveland is a thoughtful and patie

- Page 317 and 318: psychology dept, the systems analys

- Page 319 and 320: Education for Art/ Art for educatio

- Page 321 and 322: 1961). And in this respect the lang

- Page 323 and 324: situation, its causes and consequen

- Page 325 and 326: Further information: http://www.cul

- Page 327 and 328: in the post modern, been heavily cr

- Page 329 and 330: more than one sense, and in a sense

- Page 331 and 332: etween representation and depresent

- Page 333 and 334: can appear so through praxis and be

- Page 335 and 336: Text/Context. Fabric/Webs Santiago

- Page 337 and 338: artistic - is ‘only’ concerned

- Page 339: For some decades one would travel t

- Page 343 and 344: To bring about a change in the usua

- Page 345 and 346: Public for art/ Art for the public

- Page 347 and 348: The great question would therefore

- Page 349 and 350: Thoughts for the archipelago Ted Pu

- Page 351 and 352: for a public art project was concei

- Page 353 and 354: that it was time to start “constr

- Page 355 and 356: alternate sociality, a free meal...

- Page 357 and 358: Contemporary utopias for collective

- Page 359 and 360: itself, since the possibility of an

- Page 361 and 362: the performance of success and pros

- Page 363 and 364: supported by reason, by the univers

- Page 365 and 366: ves the problem of injustice and so

- Page 367 and 368: Web-makers of diffusion Alfredo Oli

- Page 369 and 370: the unforeseen, to emerge. This is

- Page 371 and 372: elationship between the productions

- Page 373 and 374: August 3, 1991 (first recording of

- Page 375 and 376: “Ever, you go out with the questi

- Page 377 and 378: alludes to madness, and they are un

- Page 379 and 380: conditions for communicability, und

- Page 381 and 382: and subjectifying proposals, making

- Page 383 and 384: desired production spaces in the co

- Page 385 and 386: promoting their circulation, reduci

- Page 387 and 388: I invite you to look and listen, an

- Page 390 and 391:

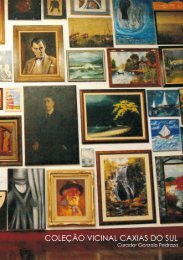

Da esquerda para direita e de cima

- Page 392:

Oficina “E surge um Espaço...”

- Page 395 and 396:

Da esquerda para direita e de cima

- Page 397 and 398:

FUNDAÇÃO BIENAL DE ARTES VISUAIS

- Page 399:

Patrocinador Apoiadores Apoiadores