SKT. NIKOLAJ KIRKE - Danmarks Kirker - Nationalmuseet

SKT. NIKOLAJ KIRKE - Danmarks Kirker - Nationalmuseet

SKT. NIKOLAJ KIRKE - Danmarks Kirker - Nationalmuseet

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

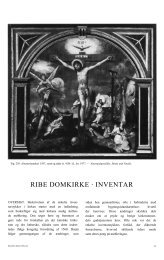

with paintings (nos. 2, 4, 5), and among other<br />

things stand out with their rare allegorical subjects.<br />

Four others (nos. 6, 7, 8, 9) very unusually<br />

consist of small black stone tablets with an ingeniously<br />

etched calligraphic inscription, signed<br />

on three of them by Villads Pedersen Trellund in<br />

Ribe, 1616. Here as elsewhere in the church, one<br />

gets a sense of the same rich cultural life as flourished<br />

in Renaissance Ribe.<br />

From the second half of the 1600s four carved<br />

sepulchral tablets in an exuberant ‘auricular’ (Ohrmuschel)<br />

style can be mentioned, three of them<br />

a scribed to the Middelfart woodcarver Hans<br />

Bang (no. 11, tablet remains no. 2, and tablet<br />

no. 1 in the Roed and Riis Chapel). Otherwise<br />

the sepulchral tablets from this time were usually<br />

in stone, the most prestigious in varicoloured<br />

marble. The monuments to the bishops Ancher<br />

and Mathias Anchersen should be singled out in<br />

this group; their sepulchral tablets from 1729 and<br />

1770 (nos. 12-13) can be attributed to the best<br />

sculptors in Copenhagen. The former may be the<br />

work of Christian Conrad Gercken; the latter is<br />

certainly by Johannes Wiedewelt.<br />

No fewer than 91 tombstones are known from<br />

the church, 37 of these preserved, and ten that<br />

are only fragments. The remaining 44 are known<br />

partly from transcripts and drawings, partly<br />

from brief mentions in the sources. Of the oldest<br />

tombstones, which go back to the 15th-16th<br />

century, many are aristocratic, including the only<br />

figured stone (no. 2), laid c. 1540 over Hans Johansen<br />

Lindenov of Fovslet, and unique in showing,<br />

under the feet of the deceased, a representation<br />

of a cadaver (a transi). Another aristocratic<br />

figured stone, laid c. 1574 over Morten Svendsen<br />

of ‘Refdal’, has now vanished (†no. 2).<br />

The 17th-century tombstones, mainly those<br />

of burghers, reflect the Renaissance fondness<br />

for cartouche framing and portal structures. A<br />

couple of stones have a special form best known<br />

from North Schleswig/South Jutland and from<br />

the churches in Ribe: an angel inside a portal<br />

holding out a shield-like ‘badge’ or an inscribed<br />

tablet in cartouche (nos. 6, 16 - cf. also no. 15).<br />

Other stones were probably produced locally,<br />

such as a series with characteristic small angels in<br />

ENGLISH SUMMARY<br />

811<br />

the corners, blowing slender trumpets (nos. 12,<br />

15, 16, 17, fragments no. 6 and 7). The tombstones<br />

of clerics are especially recognizable with<br />

their copious inscriptions over the whole width<br />

of the stone (nos. 18, 19, 24).<br />

After the mid-17th century there was a gradual<br />

breakdown of the architectural structure of the<br />

tombstones. Instead decoration took over, first in<br />

the form of auricular ornaments (most clearly in<br />

no. 23) and from c. 1700 in the form of High<br />

Baroque acanthus leaves. Especially popular was<br />

a form with an inscription in large laurel wreaths<br />

surrounded by religious figures and scenes (nos.<br />

20, 22, 25, 27). Among the few stones from the<br />

eighteenth century there are a couple of offshoots<br />

of this tradition (nos. 33, 34).<br />

Like the tombstones, the sepulchral tablets and<br />

a number of military tomb banners refer to burials<br />

in the floor. Some of these could be burials ‘in<br />

earth’, others in low brick chambers, so-called<br />

closed burials, which could be opened through a<br />

hatch or by lifting the tombstone when a new<br />

coffin was to be deposited. An ordinance on<br />

burials from 1601 states that in this area there had<br />

been ‘much impropriety’. This was among other<br />

reasons because in the best places the deceased<br />

were dug up before complete decomposition so<br />

that others could take over the tombs.<br />

The chancel was clearly the burial place for the<br />

clerics, although others could also buy a place<br />

there, for example Mayor Jep Hansen Bøgvad,<br />

who in 1632 paid 50 Dl. for a (closed) burial<br />

in the chancel. The North Chapel, or the ‘New<br />

Church’, belonged to the Castle, which could<br />

grant free burial there. This was typically granted<br />

to the castle officers, who were not rarely of foreign<br />

origin. Thus in 1614 Ulrik Hovri, who had<br />

been born in Switzerland, was granted free burial<br />

there on the orders of the Royal Cupbearer (cf.<br />

also tombstone no. 21). In the ‘New Church’ a<br />

number of Swedish officers were also buried in<br />

1644, but against payment.<br />

Besides the closed burials there were also a<br />

number of ‘open burials’ or sepulchral chapels<br />

with the coffins standing freely on the floor.<br />

The church has preserved two such chapels, the<br />

Been feldt Chapel and the Roed and Riis Chapel,