413047-Underground-Commercial-Sex-Economy

413047-Underground-Commercial-Sex-Economy

413047-Underground-Commercial-Sex-Economy

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

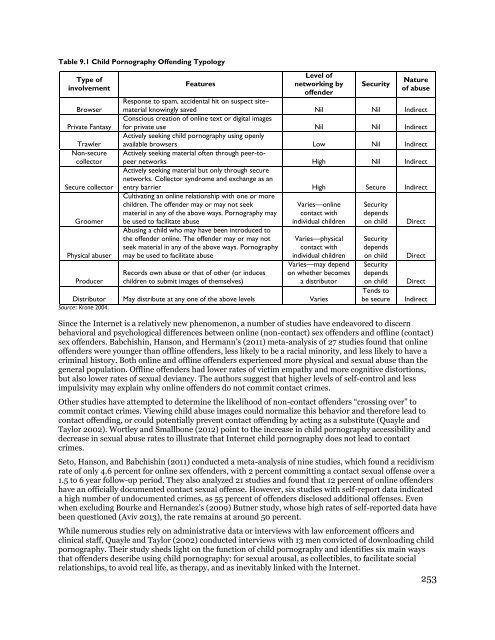

Table 9.1 Child Pornography Offending Typology<br />

Type of<br />

involvement<br />

Browser<br />

Private Fantasy<br />

Trawler<br />

Non-secure<br />

collector<br />

Secure collector<br />

Groomer<br />

Physical abuser<br />

Producer<br />

Features<br />

Level of<br />

networking by<br />

offender<br />

Security<br />

Nature<br />

of abuse<br />

Response to spam, accidental hit on suspect site–<br />

material knowingly saved Nil Nil Indirect<br />

Conscious creation of online text or digital images<br />

for private use Nil Nil Indirect<br />

Actively seeking child pornography using openly<br />

available browsers Low Nil Indirect<br />

Actively seeking material often through peer-topeer<br />

networks High Nil Indirect<br />

Actively seeking material but only through secure<br />

networks. Collector syndrome and exchange as an<br />

entry barrier High Secure Indirect<br />

Cultivating an online relationship with one or more<br />

children. The offender may or may not seek<br />

material in any of the above ways. Pornography may<br />

be used to facilitate abuse<br />

Abusing a child who may have been introduced to<br />

the offender online. The offender may or may not<br />

seek material in any of the above ways. Pornography<br />

may be used to facilitate abuse<br />

Records own abuse or that of other (or induces<br />

children to submit images of themselves)<br />

Varies—online<br />

contact with<br />

individual children<br />

Varies—physical<br />

contact with<br />

individual children<br />

Varies—may depend<br />

on whether becomes<br />

a distributor<br />

Distributor May distribute at any one of the above levels Varies<br />

Source: Krone 2004.<br />

Security<br />

depends<br />

on child<br />

Security<br />

depends<br />

on child<br />

Security<br />

depends<br />

on child<br />

Tends to<br />

be secure<br />

Direct<br />

Direct<br />

Direct<br />

Indirect<br />

Since the Internet is a relatively new phenomenon, a number of studies have endeavored to discern<br />

behavioral and psychological differences between online (non-contact) sex offenders and offline (contact)<br />

sex offenders. Babchishin, Hanson, and Hermann’s (2011) meta-analysis of 27 studies found that online<br />

offenders were younger than offline offenders, less likely to be a racial minority, and less likely to have a<br />

criminal history. Both online and offline offenders experienced more physical and sexual abuse than the<br />

general population. Offline offenders had lower rates of victim empathy and more cognitive distortions,<br />

but also lower rates of sexual deviancy. The authors suggest that higher levels of self-control and less<br />

impulsivity may explain why online offenders do not commit contact crimes.<br />

Other studies have attempted to determine the likelihood of non-contact offenders “crossing over” to<br />

commit contact crimes. Viewing child abuse images could normalize this behavior and therefore lead to<br />

contact offending, or could potentially prevent contact offending by acting as a substitute (Quayle and<br />

Taylor 2002). Wortley and Smallbone (2012) point to the increase in child pornography accessibility and<br />

decrease in sexual abuse rates to illustrate that Internet child pornography does not lead to contact<br />

crimes.<br />

Seto, Hanson, and Babchishin (2011) conducted a meta-analysis of nine studies, which found a recidivism<br />

rate of only 4.6 percent for online sex offenders, with 2 percent committing a contact sexual offense over a<br />

1.5 to 6 year follow-up period. They also analyzed 21 studies and found that 12 percent of online offenders<br />

have an officially documented contact sexual offense. However, six studies with self-report data indicated<br />

a high number of undocumented crimes, as 55 percent of offenders disclosed additional offenses. Even<br />

when excluding Bourke and Hernandez’s (2009) Butner study, whose high rates of self-reported data have<br />

been questioned (Aviv 2013), the rate remains at around 50 percent.<br />

While numerous studies rely on administrative data or interviews with law enforcement officers and<br />

clinical staff, Quayle and Taylor (2002) conducted interviews with 13 men convicted of downloading child<br />

pornography. Their study sheds light on the function of child pornography and identifies six main ways<br />

that offenders describe using child pornography: for sexual arousal, as collectibles, to facilitate social<br />

relationships, to avoid real life, as therapy, and as inevitably linked with the Internet.<br />

253