KANT'S CRITIQUE OF TELEOLOGY IN BIOLOGICAL EXPLANATION

KANT'S CRITIQUE OF TELEOLOGY IN BIOLOGICAL EXPLANATION

KANT'S CRITIQUE OF TELEOLOGY IN BIOLOGICAL EXPLANATION

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

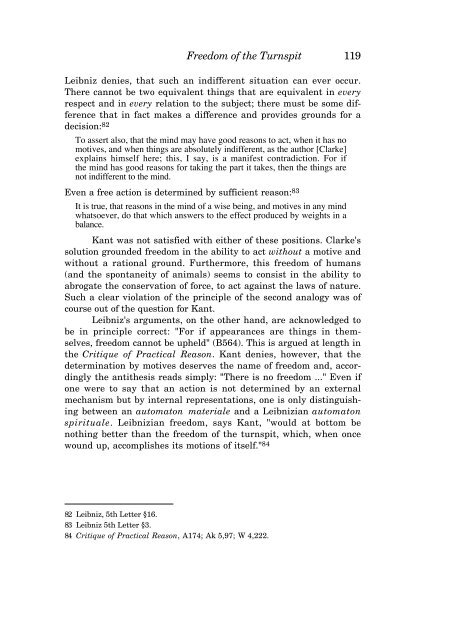

Freedom of the Turnspit 119<br />

Leibniz denies, that such an indifferent situation can ever occur.<br />

There cannot be two equivalent things that are equivalent in every<br />

respect and in every relation to the subject; there must be some difference<br />

that in fact makes a difference and provides grounds for a<br />

decision: 82<br />

To assert also, that the mind may have good reasons to act, when it has no<br />

motives, and when things are absolutely indifferent, as the author [Clarke]<br />

explains himself here; this, I say, is a manifest contradiction. For if<br />

the mind has good reasons for taking the part it takes, then the things are<br />

not indifferent to the mind.<br />

Even a free action is determined by sufficient reason: 83<br />

It is true, that reasons in the mind of a wise being, and motives in any mind<br />

whatsoever, do that which answers to the effect produced by weights in a<br />

balance.<br />

Kant was not satisfied with either of these positions. Clarke's<br />

solution grounded freedom in the ability to act without a motive and<br />

without a rational ground. Furthermore, this freedom of humans<br />

(and the spontaneity of animals) seems to consist in the ability to<br />

abrogate the conservation of force, to act against the laws of nature.<br />

Such a clear violation of the principle of the second analogy was of<br />

course out of the question for Kant.<br />

Leibniz's arguments, on the other hand, are acknowledged to<br />

be in principle correct: "For if appearances are things in themselves,<br />

freedom cannot be upheld" (B564). This is argued at length in<br />

the Critique of Practical Reason. Kant denies, however, that the<br />

determination by motives deserves the name of freedom and, accordingly<br />

the antithesis reads simply: "There is no freedom ..." Even if<br />

one were to say that an action is not determined by an external<br />

mechanism but by internal representations, one is only distinguishing<br />

between an automaton materiale and a Leibnizian automaton<br />

spirituale. Leibnizian freedom, says Kant, "would at bottom be<br />

nothing better than the freedom of the turnspit, which, when once<br />

wound up, accomplishes its motions of itself." 84<br />

82 Leibniz, 5th Letter §16.<br />

83 Leibniz 5th Letter §3.<br />

84 Critique of Practical Reason, A174; Ak 5,97; W 4,222.