KANT'S CRITIQUE OF TELEOLOGY IN BIOLOGICAL EXPLANATION

KANT'S CRITIQUE OF TELEOLOGY IN BIOLOGICAL EXPLANATION

KANT'S CRITIQUE OF TELEOLOGY IN BIOLOGICAL EXPLANATION

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

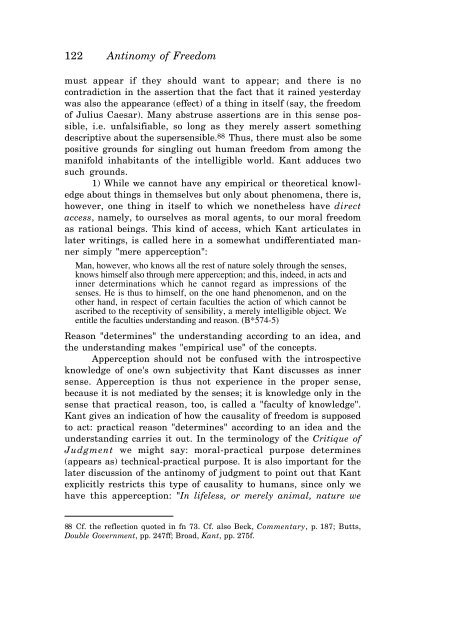

122 Antinomy of Freedom<br />

must appear if they should want to appear; and there is no<br />

contradiction in the assertion that the fact that it rained yesterday<br />

was also the appearance (effect) of a thing in itself (say, the freedom<br />

of Julius Caesar). Many abstruse assertions are in this sense possible,<br />

i.e. unfalsifiable, so long as they merely assert something<br />

descriptive about the supersensible. 88 Thus, there must also be some<br />

positive grounds for singling out human freedom from among the<br />

manifold inhabitants of the intelligible world. Kant adduces two<br />

such grounds.<br />

1) While we cannot have any empirical or theoretical knowledge<br />

about things in themselves but only about phenomena, there is,<br />

however, one thing in itself to which we nonetheless have direct<br />

access, namely, to ourselves as moral agents, to our moral freedom<br />

as rational beings. This kind of access, which Kant articulates in<br />

later writings, is called here in a somewhat undifferentiated manner<br />

simply "mere apperception":<br />

Man, however, who knows all the rest of nature solely through the senses,<br />

knows himself also through mere apperception; and this, indeed, in acts and<br />

inner determinations which he cannot regard as impressions of the<br />

senses. He is thus to himself, on the one hand phenomenon, and on the<br />

other hand, in respect of certain faculties the action of which cannot be<br />

ascribed to the receptivity of sensibility, a merely intelligible object. We<br />

entitle the faculties understanding and reason. (B*574-5)<br />

Reason "determines" the understanding according to an idea, and<br />

the understanding makes "empirical use" of the concepts.<br />

Apperception should not be confused with the introspective<br />

knowledge of one's own subjectivity that Kant discusses as inner<br />

sense. Apperception is thus not experience in the proper sense,<br />

because it is not mediated by the senses; it is knowledge only in the<br />

sense that practical reason, too, is called a "faculty of knowledge".<br />

Kant gives an indication of how the causality of freedom is supposed<br />

to act: practical reason "determines" according to an idea and the<br />

understanding carries it out. In the terminology of the Critique of<br />

Judgment we might say: moral-practical purpose determines<br />

(appears as) technical-practical purpose. It is also important for the<br />

later discussion of the antinomy of judgment to point out that Kant<br />

explicitly restricts this type of causality to humans, since only we<br />

have this apperception: "In lifeless, or merely animal, nature we<br />

88 Cf. the reflection quoted in fn 73. Cf. also Beck, Commentary, p. 187; Butts,<br />

Double Government, pp. 247ff; Broad, Kant, pp. 275f.