Assisting the older driver - SWOV

Assisting the older driver - SWOV

Assisting the older driver - SWOV

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Assisting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>older</strong> <strong>driver</strong><br />

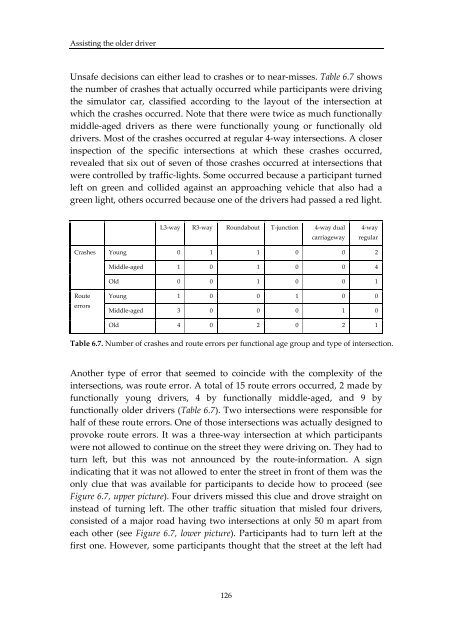

Unsafe decisions can ei<strong>the</strong>r lead to crashes or to near‐misses. Table 6.7 shows<br />

<strong>the</strong> number of crashes that actually occurred while participants were driving<br />

<strong>the</strong> simulator car, classified according to <strong>the</strong> layout of <strong>the</strong> intersection at<br />

which <strong>the</strong> crashes occurred. Note that <strong>the</strong>re were twice as much functionally<br />

middle‐aged <strong>driver</strong>s as <strong>the</strong>re were functionally young or functionally old<br />

<strong>driver</strong>s. Most of <strong>the</strong> crashes occurred at regular 4‐way intersections. A closer<br />

inspection of <strong>the</strong> specific intersections at which <strong>the</strong>se crashes occurred,<br />

revealed that six out of seven of those crashes occurred at intersections that<br />

were controlled by traffic‐lights. Some occurred because a participant turned<br />

left on green and collided against an approaching vehicle that also had a<br />

green light, o<strong>the</strong>rs occurred because one of <strong>the</strong> <strong>driver</strong>s had passed a red light.<br />

L3‐way R3‐way Roundabout T‐junction 4‐way dual<br />

carriageway<br />

4‐way<br />

regular<br />

Crashes<br />

Young 0 1 1 0 0 2<br />

Middle‐aged 1 0 1 0 0 4<br />

Old 0 0 1 0 0 1<br />

Route<br />

errors<br />

Young 1 0 0 1 0 0<br />

Middle‐aged 3 0 0 0 1 0<br />

Old 4 0 2 0 2 1<br />

Table 6.7. Number of crashes and route errors per functional age group and type of intersection.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r type of error that seemed to coincide with <strong>the</strong> complexity of <strong>the</strong><br />

intersections, was route error. A total of 15 route errors occurred, 2 made by<br />

functionally young <strong>driver</strong>s, 4 by functionally middle‐aged, and 9 by<br />

functionally <strong>older</strong> <strong>driver</strong>s (Table 6.7). Two intersections were responsible for<br />

half of <strong>the</strong>se route errors. One of those intersections was actually designed to<br />

provoke route errors. It was a three‐way intersection at which participants<br />

were not allowed to continue on <strong>the</strong> street <strong>the</strong>y were driving on. They had to<br />

turn left, but this was not announced by <strong>the</strong> route‐information. A sign<br />

indicating that it was not allowed to enter <strong>the</strong> street in front of <strong>the</strong>m was <strong>the</strong><br />

only clue that was available for participants to decide how to proceed (see<br />

Figure 6.7, upper picture). Four <strong>driver</strong>s missed this clue and drove straight on<br />

instead of turning left. The o<strong>the</strong>r traffic situation that misled four <strong>driver</strong>s,<br />

consisted of a major road having two intersections at only 50 m apart from<br />

each o<strong>the</strong>r (see Figure 6.7, lower picture). Participants had to turn left at <strong>the</strong><br />

first one. However, some participants thought that <strong>the</strong> street at <strong>the</strong> left had<br />

126