- Page 1:

• David Begg, Gianluigi Vernasca,

- Page 4 and 5:

Economics 10th Edition David Begg,

- Page 7 and 8:

Brief Table of Contents Preface xii

- Page 9 and 10:

5 Consumer choice and demand decisi

- Page 11 and 12:

PART FOUR Macroeconomics l 5 Introd

- Page 13 and 14:

PART FIVE The world economy 28 Inte

- Page 15 and 16:

Changes to the tenth edition After

- Page 17 and 18:

Guided tour In addition to illustra

- Page 19 and 20:

Aiding Understanding Hy the end of

- Page 21 and 22:

Rent ceiling in Sweden* More on pri

- Page 23 and 24:

13 General vs partial equilibrium:

- Page 25 and 26:

26 Growth and competition* Case Neo

- Page 27 and 28:

Cl INSTRUCTORS ... Would you like y

- Page 29 and 30:

Additional technology to enhance le

- Page 31 and 32:

Custom Publishing Solutions • cre

- Page 33 and 34:

Acknowledgements for the tenth edit

- Page 35 and 36:

Finally, special thanks to the foll

- Page 38:

---.. . - Introduction Economics is

- Page 41 and 42:

CHAPTER 1 Economics and the economy

- Page 43 and 44:

CHAPTER 1 Economics and the economy

- Page 45 and 46:

CHAPTER 1 Economics and the economy

- Page 47 and 48:

CHAPTER 1 Economics and the economy

- Page 49 and 50:

CHAPTER 1 Economics and the economy

- Page 51 and 52:

CHAPTER 1 Economics and the economy

- Page 53 and 54:

CHAPTER 1 Economics and the economy

- Page 55 and 56:

CHAPTER 1 Economics and the economy

- Page 57 and 58:

CHAPTER 1 Economics and the economy

- Page 59 and 60:

Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 61 and 62:

CHAPTER 2 Tools of economic analysi

- Page 63 and 64:

CHAPTER 2 Tools of economic analysi

- Page 65 and 66:

CHAPTER 2 Tools of economic analysi

- Page 67 and 68:

CHAPTER 2 Tools of economic analysi

- Page 69 and 70:

CHAPTER 2 Tools of economic analysi

- Page 71 and 72:

CHAPTER 2 Tools of economic analysi

- Page 73 and 74:

CHAPTER 2 Tools of economic analysi

- Page 75 and 76:

CHAPTER 2 Tools of economic analysi

- Page 77 and 78:

CHAPTER 2 Tools of economic analysi

- Page 79 and 80:

Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 81 and 82:

CHAPTER 3 Demand, supply and the ma

- Page 83 and 84:

CHAPTER 3 Demand, supply and the ma

- Page 85 and 86:

CHAPTER 3 Demand, supply and the ma

- Page 87 and 88:

CHAPTER 3 Demand, supply and the ma

- Page 89 and 90:

CHAPTER 3 Demand, supply and the ma

- Page 91 and 92:

CHAPTER 3 Demand, supply and the ma

- Page 93 and 94:

CHAPTER 3 Demand, supply and the ma

- Page 95 and 96:

CHAPTER 3 Demand, supply and the ma

- Page 97 and 98:

CHAPTER 3 Demand, supply and the ma

- Page 99 and 100:

CHAPTER 3 Demand, supply and the ma

- Page 102 and 103:

Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 104 and 105:

4.1 The price responsiveness of dem

- Page 106 and 107:

4.1 The price responsiveness of dem

- Page 108 and 109:

4.1 The price responsiveness of dem

- Page 110 and 111:

4.2 Price, quantity demanded and to

- Page 112 and 113:

4.2 Price, quantity demanded and to

- Page 114 and 115:

4.4 Short run and long run simultan

- Page 116 and 117:

4.6 The effect of income on demand

- Page 118 and 119:

4.6 The effect of income on demand

- Page 120 and 121:

4.8 Elasticity of supply The elasti

- Page 122 and 123:

4.9 Who really pays the tax? S' - G

- Page 124 and 125:

Summary What are the effects of the

- Page 126 and 127:

Review questions 5 Common fallacies

- Page 128 and 129:

Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 130 and 131:

5.1 Demand by a single consumer is

- Page 132 and 133:

5.1 Demand by a single consumer Ill

- Page 134 and 135:

5.1 Demand by a single consumer QF

- Page 136 and 137:

5.1 Demand by a single consumer whe

- Page 138 and 139:

5.1 Demand by a single consumer How

- Page 140 and 141:

5.2 Adjustment to income changes ou

- Page 142 and 143:

5.3 Adjustment to price changes and

- Page 144 and 145:

5.3 Adjustment to price changes Thi

- Page 146 and 147:

5.3 Adjustment to price changes imp

- Page 148 and 149:

5.3 Adjustment to price changes Q '

- Page 150 and 151:

5.5 Complements and substitutes it

- Page 152 and 153:

5.6 Transfers in kind that to the s

- Page 154 and 155:

Review questions • The market dem

- Page 156 and 157:

Our theory of consumer choice assum

- Page 158 and 159:

APPENDIX Consumer choice with measu

- Page 160 and 161:

6.2 A firm's accounts A sole trader

- Page 162 and 163:

6.2 A firm's accounts Inventories I

- Page 164 and 165:

6.2 A firm's accounts Earnings When

- Page 166 and 167:

6.4 Corporate finance and corporate

- Page 168 and 169:

6.5 The firm's supply decision Tabl

- Page 170 and 171:

6.6 Marginal cost and marginal reve

- Page 172 and 173:

6.6 Marginal cost and marginal reve

- Page 174 and 175:

6.6 Marginal cost and marginal reve

- Page 176 and 177:

6. 7 Marginal cost and marginal rev

- Page 178 and 179:

Review questions in total cost when

- Page 180 and 181:

Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 182 and 183:

7.2 Production in the short run: di

- Page 184 and 185:

7.2 Production in the short run: di

- Page 186 and 187:

7.3 Short-run costs As you can see

- Page 188 and 189:

7.3 Short-run costs 60 50 SMC - 40

- Page 190 and 191:

7.3 Short-run costs down average co

- Page 192 and 193:

7.4 A firm's output decision in the

- Page 194 and 195:

7.6 Long-run total, marginal and av

- Page 196 and 197:

7. 7 Returns to scale - "O 0 DI ..

- Page 198 and 199:

7. 7 Returns to scale Scale economi

- Page 200 and 201:

7. 7 Returns to scale Table 7.10 Mi

- Page 202 and 203:

--1-----1 7.8 The firm's long-run o

- Page 204 and 205:

Summary Summary • This chapter di

- Page 206 and 207:

Review questions 8 Suppose that fir

- Page 208 and 209:

8.1 Perfect competition Perfect com

- Page 210 and 211:

8.2 A perfectly competitive firm's

- Page 212 and 213:

8.2 A perfectly competitive firm's

- Page 214 and 215:

8.3 Industry supply curves In the s

- Page 216 and 217:

8.4 Comparative statics for a compe

- Page 218 and 219:

.. 8.6 Profit-maximizing output for

- Page 220 and 221:

8.6 Profit-maximizing output for a

- Page 222 and 223:

8. 7 Output and price under monopol

- Page 224 and 225:

8. 7 Output and price under monopol

- Page 226 and 227:

8.8 A monopoly has no supply curve

- Page 228 and 229:

8.9 Monopoly and technical change f

- Page 230 and 231:

8.10 Natural monopoly 'ti QI 0 :I P

- Page 232 and 233:

Review questions • Adding at each

- Page 234 and 235:

Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 236 and 237:

9 .1 Why market structures differ D

- Page 238 and 239:

9 .1 Why market structures differ T

- Page 240 and 241:

9.3 Oligopoly and interdependence A

- Page 242 and 243:

9.3 Oligopoly and interdependence T

- Page 244 and 245:

9.4 Game theory and interdependent

- Page 246 and 247:

9.5 Reaction functions demand curve

- Page 248 and 249:

9.5 Reaction functions Deriving the

- Page 250 and 251:

9.5 Reaction functions Mergers and

- Page 252 and 253:

9.5 Reaction functions The Stackelb

- Page 254 and 255:

9.7 Strategic entry deterrence Inno

- Page 256 and 257:

9.8 Summing up Barriers at the chec

- Page 258 and 259:

Review questions Review questions c

- Page 260 and 261:

Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 262 and 263:

I 0.1 The firm's demand for factors

- Page 264 and 265:

10.2 The firm's demand for labour i

- Page 266 and 267:

10.3 The industry demand curve for

- Page 268 and 269:

10.4 The supply of labour Table 10.

- Page 270 and 271:

10.4 The supply of labour A reducti

- Page 272 and 273:

10.5 Industry labour market equilib

- Page 274 and 275:

10.5 Industry labour market equilib

- Page 276 and 277:

10.6 Transfer earnings and economic

- Page 278 and 279:

10. 7 Do labour markets clear? Mini

- Page 280 and 281:

10. 7 Do labour markets clear? How

- Page 282 and 283:

10.8 UK wages and employment Table

- Page 284 and 285:

Summary reducing demand for both fa

- Page 286 and 287:

Review questions In a graph with th

- Page 288 and 289:

APPENDIX Isoquants and the choice o

- Page 290 and 291:

Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 292 and 293:

11.2 Rentals, interest rates and as

- Page 294 and 295:

11.2 Rentals, interest rates and as

- Page 296 and 297:

11.2 Rentals, interest rates and as

- Page 298 and 299:

11.3 Saving, investment and the rea

- Page 300 and 301:

11. 5 The supply of capital service

- Page 302 and 303:

11.6 Equilibrium and adjustment in

- Page 304 and 305:

11.8 Land and rents supply of skill

- Page 306 and 307:

11.9 Income distribution in the UK

- Page 308 and 309:

Summary of average earnings. As liv

- Page 310 and 311:

Review questions the quantity of ca

- Page 312 and 313:

Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 314 and 315:

12.l Individual attitudes to risk S

- Page 316 and 317:

12.2 Insurance and risk Life assura

- Page 318 and 319:

12.3 Asymmetric information The uti

- Page 320 and 321:

12.3 Asymmetric information Executi

- Page 322 and 323:

12.4 Uncertainty and asset returns

- Page 324 and 325:

12.5 Portfolio selection We use the

- Page 326 and 327:

12.5 Portfolio selection Conversely

- Page 328 and 329:

12.6 Efficient asset markets Beta i

- Page 330 and 331:

12.6 Efficient asset markets II Beh

- Page 332 and 333:

12. 7 More on risk You own a copper

- Page 334 and 335:

12.8 E-products 100 80 60 - - - - -

- Page 336 and 337:

12.8 E-products If Britain had to s

- Page 338 and 339:

Summary Britannica shelved Serious

- Page 340 and 341:

Review questions 4 You set up a fir

- Page 342:

Welfa re economics Normative or wel

- Page 345 and 346:

CHAPTER 13 Welfare economics Welfar

- Page 347 and 348:

CHAPTER 13 Welfare economics Perfec

- Page 349 and 350:

CHAPTER 13 Welfare economics margin

- Page 351 and 352:

CHAPTER 13 Welfare economics II) E

- Page 353 and 354:

CHAPTER 13 Welfare economics have c

- Page 355 and 356:

CHAPTER 13 Welfare economics DD Wit

- Page 357 and 358:

CHAPTER 13 Welfare economics .. ;

- Page 359 and 360:

CHAPTER 13 Welfare economics 0 Firm

- Page 361 and 362:

CHAPTER 13 Welfare economics Was th

- Page 363 and 364:

CHAPTER 13 Welfare economics 0 u -

- Page 365 and 366:

CHAPTER 13 Welfare economics benefi

- Page 367 and 368:

CHAPTER 13 Welfare economics P' "i

- Page 369 and 370:

CHAPTER 13 Welfare economics • Di

- Page 371 and 372:

CHAPTER 13 Welfare economics Q MPC

- Page 373 and 374:

CHAPTER 14 Government spending and

- Page 375 and 376:

CHAPTER 14 Government spending and

- Page 377 and 378:

CHAPTER 14 Government spending and

- Page 379 and 380:

CHAPTER 14 Government spending and

- Page 381 and 382:

CHAPTER 14 Government spending and

- Page 383 and 384:

CHAPTER 14 Government spending and

- Page 385 and 386:

CHAPTER 14 Government spending and

- Page 387 and 388:

CHAPTER 14 Government spending and

- Page 389 and 390:

CHAPTER 14 Government spending and

- Page 391 and 392:

CHAPTER 14 Government spending and

- Page 393 and 394:

CHAPTER 14 Government spending and

- Page 396 and 397:

Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 398 and 399:

15.2 Some facts Annual real output

- Page 400 and 401:

15.3 An overview Since profits are

- Page 402 and 403:

15.4 National income accounting

- Page 404 and 405:

15.4 National income accounting Sav

- Page 406 and 407:

15.4 National income accounting phy

- Page 408 and 409:

15.4 National income accounting Hou

- Page 410 and 411:

15.5 What GNP measures Table l 5.3

- Page 412 and 413:

15.5 What GNP measures Table 15.4 N

- Page 414 and 415:

15.6 International comparisons Citi

- Page 416 and 417:

Review questions Review questions c

- Page 418 and 419:

Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 420 and 421:

16. l Components of aggregate deman

- Page 422 and 423:

16.2 Aggregate demand S =-A + (1 -

- Page 424 and 425:

16.3 Equilibrium output C'I ·- c -

- Page 426 and 427:

16.4 Another approach: planned savi

- Page 428 and 429:

16. 5 A fall in aggregate demand A

- Page 430 and 431:

16.7 The paradox of thrift Table 16

- Page 432 and 433:

16.8 The role of confidence The cha

- Page 434 and 435:

Review questions 2 Suppose the MPC

- Page 436 and 437:

17 .2 Government and aggregate dema

- Page 438 and 439:

17 .2 Government and aggregate dema

- Page 440 and 441:

17 .2 Government and aggregate dema

- Page 442 and 443:

17 .2 Government and aggregate dema

- Page 444 and 445:

17.4 Deficits and the fiscal stance

- Page 446 and 447:

17.5 Automatic stabilizers and disc

- Page 448 and 449:

17 .6 The national debt and the def

- Page 450 and 451:

17. 7 Foreign trade and income dete

- Page 452 and 453:

17. 7 Foreign trade and income dete

- Page 454 and 455:

Summary and employment. In Figure 1

- Page 456 and 457:

Review questions 2 The government s

- Page 458 and 459:

18. 1 Money and its functions The m

- Page 460 and 461:

18.2 Modern banking M_o_d_er_n_ha

- Page 462 and 463:

18.3 How banks create money How did

- Page 464 and 465:

18.4 Financial crises However, ther

- Page 466 and 467:

18.4 Financial crises UK bank inter

- Page 468 and 469:

18.5 The traditional theory of mone

- Page 470 and 471:

18.6 UK money supply after the 2006

- Page 472 and 473:

18. 7 The demand for money flow and

- Page 474 and 475:

18. 7 The demand for money Table 18

- Page 476 and 477:

Review questions • Financial dere

- Page 478 and 479:

Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 480 and 481:

19.2 Traditional means of monetary

- Page 482 and 483:

19 .3 Lender of last resort Second,

- Page 484 and 485:

19.4 Equilibrium in financial marke

- Page 486 and 487:

19.5 Monetary control However, more

- Page 488 and 489:

19.5 Monetary control UK quantitati

- Page 490 and 491:

19. 7 The transmission mechanism AD

- Page 492 and 493:

19. 7 The transmission mechanism Wh

- Page 494 and 495:

19. 7 The transmission mechanism In

- Page 496 and 497:

19. 7 The transmission mechanism He

- Page 498 and 499:

Review questions • A higher inter

- Page 500 and 501:

Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 502 and 503:

20.2 The IS-LM model T_he_IS_-_L_

- Page 504 and 505:

20.2 The IS-LM model Until 2008 mon

- Page 506 and 507:

20.3 The IS-LM model in action Fisc

- Page 508 and 509:

20.4 Shocks to money demand Hence,

- Page 510 and 511:

20.5 The policy mix IS schedule, IS

- Page 512 and 513:

20.6 The effect of future taxes Que

- Page 514 and 515:

Summary helped explain positive UK

- Page 516 and 517:

Review questions IS-LM diagram, rec

- Page 518 and 519:

21. l Inflation and aggregate deman

- Page 520 and 521:

21.2 Aggregate supply demand. The A

- Page 522 and 523: 21.3 Equilibrium inflation AS0 AS,

- Page 524 and 525: 21.3 Equilibrium inflation It was c

- Page 526 and 527: 21.4 The labour market and wage beh

- Page 528 and 529: 21.6 The adjustment process The eco

- Page 530 and 531: 21. 7 Sluggish adjustment to shocks

- Page 532 and 533: 21.8 Trade-offs in monetary objecti

- Page 534 and 535: 21.8 Trade-offs in monetary objecti

- Page 536 and 537: Review questions • In practice, w

- Page 538 and 539: Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 540 and 541: 22. l Money and inflation rises wit

- Page 542 and 543: 22.2 Inflation and interest rates N

- Page 544 and 545: 22.3 Inflation, money and deficits

- Page 546 and 547: 22.4 Inflation, unemployment and ou

- Page 548 and 549: 22.4 Inflation, unemployment and ou

- Page 550 and 551: 22.4 Inflation, unemployment and ou

- Page 552 and 553: 22.5 The costs of inflation find th

- Page 554 and 555: 22.5 The costs of inflation You los

- Page 556 and 557: 22.6 Controlling inflation Without

- Page 558 and 559: 22. 7 The Monetary Policy Committee

- Page 560 and 561: Summary 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 He

- Page 562 and 563: Review questions Money growth (%) I

- Page 564 and 565: Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 566 and 567: 23. l The labour market may simply

- Page 568 and 569: 23.2 Analysing unemployment The fig

- Page 570 and 571: 23.2 Analysing unemployment of an h

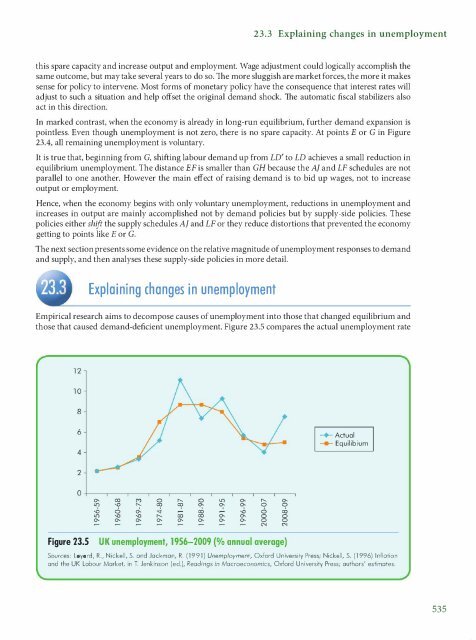

- Page 574 and 575: 23.3 Explaining changes in unemploy

- Page 576 and 577: 23.3 Explaining changes in unemploy

- Page 578 and 579: 23.4 Cyclical fluctuations in unemp

- Page 580 and 581: 23.5 The cost of unemployment Count

- Page 582 and 583: 23.5 The cost of unemployment in th

- Page 584 and 585: Review questions • Most European

- Page 586 and 587: Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 588 and 589: 24.1 The foreign exchange market do

- Page 590 and 591: 24.2 Exchange rate regimes ... ii)

- Page 592 and 593: 24.3 The balance of payments statis

- Page 594 and 595: 24.4 The real exchange rate In row

- Page 596 and 597: 24.6 The financial account Table 24

- Page 598 and 599: 24.6 The financial account This sec

- Page 600 and 601: 24. 7 Internal and external balance

- Page 602 and 603: 24.8 The long-run equilibrium real

- Page 604 and 605: Summary This figure is helpful in t

- Page 606 and 607: Review questions Review questions c

- Page 608 and 609: Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 610 and 611: 25. l Fixed exchange rates So far,

- Page 612 and 613: 25. l Fixed exchange rates Gordon B

- Page 614 and 615: 25. l Fixed exchange rates A shock

- Page 616 and 617: 25.3 Devaluation 1 .., Devaluation

- Page 618 and 619: 25.3 Devaluation Table 25.1 The 196

- Page 620 and 621: 25.4 Floating exchange rates UK. Af

- Page 622 and 623:

25.5 Monetary and fiscal policy und

- Page 624 and 625:

25.5 Monetary and fiscal policy und

- Page 626 and 627:

Summary Summary • With a fixed ex

- Page 628 and 629:

Review questions 11 The following t

- Page 630 and 631:

26. 1 Economic growth Table 26.1 Re

- Page 632 and 633:

26.2 Growth: an overview In the lon

- Page 634 and 635:

26.3 Technical knowledge Learning b

- Page 636 and 637:

26.4 Growth and accumulation increa

- Page 638 and 639:

26.5 Growth through technical progr

- Page 640 and 641:

26.6 Growth in the OECD II : e!p ;:

- Page 642 and 643:

26.6 Growth in the OECD Within the

- Page 644 and 645:

26.6 Growth in the OECD Annual real

- Page 646 and 647:

26.8 The costs of growth rate g? If

- Page 648 and 649:

Review questions • Potential outp

- Page 650 and 651:

Learning Outcomes By the end of thi

- Page 652 and 653:

2 7 .1 Trend and cycle: statistics

- Page 654 and 655:

27.2 Theories of the business cycle

- Page 656 and 657:

27.2 Theories of the business cycle

- Page 658 and 659:

.. 27.2 Theories of the business cy

- Page 660 and 661:

27 .3 Real business cycles provides

- Page 662 and 663:

27.4 Towards a consensus: supply-si

- Page 664 and 665:

27.5 An international business cycl

- Page 666 and 667:

Review questions • Some swings in

- Page 668:

The world economy Part Five focuses

- Page 671 and 672:

CHAPTER 28 International trade Is t

- Page 673 and 674:

CHAPTER 28 International trade Tabl

- Page 675 and 676:

CHAPTER 28 International trade The

- Page 677 and 678:

CHAPTER 28 International trade Comp

- Page 679 and 680:

CHAPTER 28 International trade Conv

- Page 681 and 682:

CHAPTER 28 International trade Fanc

- Page 683 and 684:

CHAPTER 28 International trade The

- Page 685 and 686:

CHAPTER 28 International trade High

- Page 687 and 688:

CHAPTER 28 International trade thei

- Page 689 and 690:

CHAPTER 28 International trade Of c

- Page 691 and 692:

CHAPTER 28 International trade Conc

- Page 693 and 694:

CHAPTER 28 International trade SS

- Page 695 and 696:

CHAPTER 28 International trade 7 Wh

- Page 697 and 698:

CHAPTER 29 Exchange rate regimes Ta

- Page 699 and 700:

CHAPTER 29 Exchange rate regimes co

- Page 701 and 702:

CHAPTER 29 Exchange rate regimes re

- Page 703 and 704:

CHAPTER 29 Exchange rate regimes 0.

- Page 705 and 706:

CHAPTER 29 Exchange rate regimes It

- Page 707 and 708:

CHAPTER 29 Exchange rate regimes Ta

- Page 709 and 710:

CHAPTER 29 Exchange rate regimes 0

- Page 711 and 712:

CHAPTER 29 Exchange rate regimes th

- Page 713 and 714:

CHAPTER 29 Exchange rate regimes 14

- Page 715 and 716:

CHAPTER 29 Exchange rate regimes 0

- Page 717 and 718:

CHAPTER 29 Exchange rate regimes

- Page 720 and 721:

Activity 1.1 (a) (b) Activity 2.1 (

- Page 722 and 723:

Answers to activity questions Activ

- Page 724 and 725:

Answers to activity questions Activ

- Page 726 and 727:

Absolute advantage an individual, c

- Page 728 and 729:

Glossary Demand for money a demand

- Page 730 and 731:

Glossary Gross domestic product (GD

- Page 732 and 733:

Glossary Marginal product the margi

- Page 734 and 735:

Glossary Percentage change the abso

- Page 736 and 737:

Glossary Sole trader a business own

- Page 738 and 739:

A absolute advantage 11-12 internat

- Page 740 and 741:

Index commodity composition of trad

- Page 742 and 743:

Index elasticity of supply 82-4 ele

- Page 744 and 745:

Index happiness 594 new products 59

- Page 746 and 747:

Index Laffer curve supply-side econ

- Page 748 and 749:

Index exports 369 foreign countries

- Page 750 and 751:

Index reading diagrams 34-5 real bu

- Page 752 and 753:

Index future taxes effect 475-7 gov