A Foundation Course in Reading German, 2017a

A Foundation Course in Reading German, 2017a

A Foundation Course in Reading German, 2017a

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Offl<strong>in</strong>e Textbook | A <strong>Foundation</strong> <strong>Course</strong> <strong>in</strong> Read<strong>in</strong>g <strong>German</strong><br />

https://courses.dcs.wisc.edu/wp/read<strong>in</strong>ggerman/pr<strong>in</strong>t-entire-textbook/<br />

Page 67 of 151<br />

12/8/2017<br />

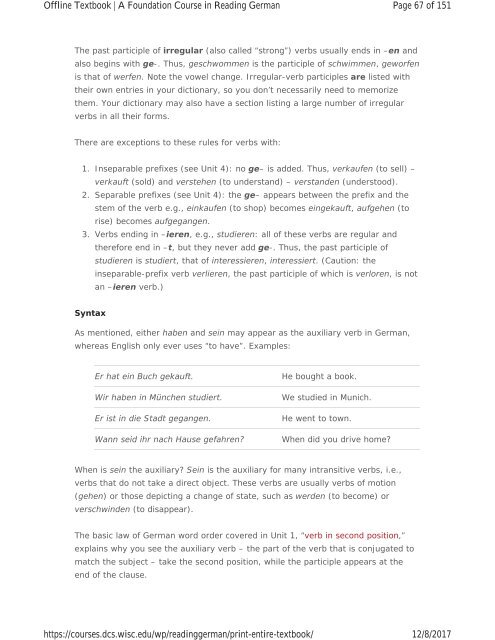

The past participle of irregular (also called “strong”) verbs usually ends <strong>in</strong> –en and<br />

also beg<strong>in</strong>s with ge-. Thus, geschwommen is the participle of schwimmen, geworfen<br />

is that of werfen. Note the vowel change. Irregular-verb participles are listed with<br />

their own entries <strong>in</strong> your dictionary, so you don’t necessarily need to memorize<br />

them. Your dictionary may also have a section list<strong>in</strong>g a large number of irregular<br />

verbs <strong>in</strong> all their forms.<br />

There are exceptions to these rules for verbs with:<br />

1. Inseparable prefixes (see Unit 4): no ge– is added. Thus, verkaufen (to sell) –<br />

verkauft (sold) and verstehen (to understand) – verstanden (understood).<br />

2. Separable prefixes (see Unit 4): the ge– appears between the prefix and the<br />

stem of the verb e.g., e<strong>in</strong>kaufen (to shop) becomes e<strong>in</strong>gekauft, aufgehen (to<br />

rise) becomes aufgegangen.<br />

3. Verbs end<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> –ieren, e.g., studieren: all of these verbs are regular and<br />

therefore end <strong>in</strong> –t, but they never add ge-. Thus, the past participle of<br />

studieren is studiert, that of <strong>in</strong>teressieren, <strong>in</strong>teressiert. (Caution: the<br />

<strong>in</strong>separable-prefix verb verlieren, the past participle of which is verloren, is not<br />

an –ieren verb.)<br />

Syntax<br />

As mentioned, either haben and se<strong>in</strong> may appear as the auxiliary verb <strong>in</strong> <strong>German</strong>,<br />

whereas English only ever uses “to have”. Examples:<br />

Er hat e<strong>in</strong> Buch gekauft.<br />

Wir haben <strong>in</strong> München studiert.<br />

Er ist <strong>in</strong> die Stadt gegangen.<br />

Wann seid ihr nach Hause gefahren?<br />

He bought a book.<br />

We studied <strong>in</strong> Munich.<br />

He went to town.<br />

When did you drive home?<br />

When is se<strong>in</strong> the auxiliary? Se<strong>in</strong> is the auxiliary for many <strong>in</strong>transitive verbs, i.e.,<br />

verbs that do not take a direct object. These verbs are usually verbs of motion<br />

(gehen) or those depict<strong>in</strong>g a change of state, such as werden (to become) or<br />

verschw<strong>in</strong>den (to disappear).<br />

The basic law of <strong>German</strong> word order covered <strong>in</strong> Unit 1, “verb <strong>in</strong> second position,”<br />

expla<strong>in</strong>s why you see the auxiliary verb – the part of the verb that is conjugated to<br />

match the subject – take the second position, while the participle appears at the<br />

end of the clause.