Dealing with salinity in Wheatbelt Valleys - Department of Water

Dealing with salinity in Wheatbelt Valleys - Department of Water

Dealing with salinity in Wheatbelt Valleys - Department of Water

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

services. The Government responded <strong>with</strong><br />

extensive borrow<strong>in</strong>g to fund necessary capital<br />

works, most notably the expansion <strong>of</strong> the very<br />

small exist<strong>in</strong>g railway network, the build<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

Fremantle Harbour and the development <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Frost and Burnside<br />

Goldfields <strong>Water</strong> Supply Scheme (properly called<br />

the ‘Coolgardie Goldfields <strong>Water</strong> Scheme’). The<br />

level <strong>of</strong> borrow<strong>in</strong>g was criticised by many, who felt<br />

that the State was exceed<strong>in</strong>g its ability to service<br />

its commitments (Crowley 2000).<br />

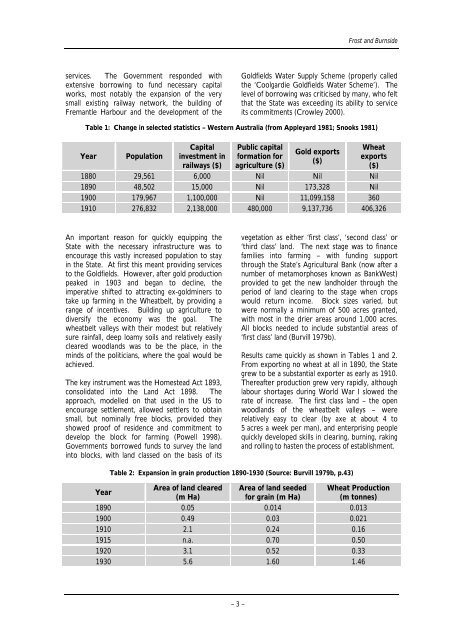

Table 1: Change <strong>in</strong> selected statistics – Western Australia (from Appleyard 1981; Snooks 1981)<br />

Year Population<br />

Capital<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong><br />

railways ($)<br />

Public capital<br />

formation for<br />

agriculture ($)<br />

Gold exports<br />

($)<br />

Wheat<br />

exports<br />

($)<br />

1880 29,561 6,000 Nil Nil Nil<br />

1890 48,502 15,000 Nil 173,328 Nil<br />

1900 179,967 1,100,000 Nil 11,099,158 360<br />

1910 276,832 2,138,000 480,000 9,137,736 406,326<br />

An important reason for quickly equipp<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

State <strong>with</strong> the necessary <strong>in</strong>frastructure was to<br />

encourage this vastly <strong>in</strong>creased population to stay<br />

<strong>in</strong> the State. At first this meant provid<strong>in</strong>g services<br />

to the Goldfields. However, after gold production<br />

peaked <strong>in</strong> 1903 and began to decl<strong>in</strong>e, the<br />

imperative shifted to attract<strong>in</strong>g ex-goldm<strong>in</strong>ers to<br />

take up farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Wheatbelt</strong>, by provid<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

range <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>centives. Build<strong>in</strong>g up agriculture to<br />

diversify the economy was the goal. The<br />

wheatbelt valleys <strong>with</strong> their modest but relatively<br />

sure ra<strong>in</strong>fall, deep loamy soils and relatively easily<br />

cleared woodlands was to be the place, <strong>in</strong> the<br />

m<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> the politicians, where the goal would be<br />

achieved.<br />

The key <strong>in</strong>strument was the Homestead Act 1893,<br />

consolidated <strong>in</strong>to the Land Act 1898. The<br />

approach, modelled on that used <strong>in</strong> the US to<br />

encourage settlement, allowed settlers to obta<strong>in</strong><br />

small, but nom<strong>in</strong>ally free blocks, provided they<br />

showed pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> residence and commitment to<br />

develop the block for farm<strong>in</strong>g (Powell 1998).<br />

Governments borrowed funds to survey the land<br />

<strong>in</strong>to blocks, <strong>with</strong> land classed on the basis <strong>of</strong> its<br />

Year<br />

vegetation as either ‘first class’, ‘second class’ or<br />

‘third class’ land. The next stage was to f<strong>in</strong>ance<br />

families <strong>in</strong>to farm<strong>in</strong>g – <strong>with</strong> fund<strong>in</strong>g support<br />

through the State’s Agricultural Bank (now after a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> metamorphoses known as BankWest)<br />

provided to get the new landholder through the<br />

period <strong>of</strong> land clear<strong>in</strong>g to the stage when crops<br />

would return <strong>in</strong>come. Block sizes varied, but<br />

were normally a m<strong>in</strong>imum <strong>of</strong> 500 acres granted,<br />

<strong>with</strong> most <strong>in</strong> the drier areas around 1,000 acres.<br />

All blocks needed to <strong>in</strong>clude substantial areas <strong>of</strong><br />

‘first class’ land (Burvill 1979b).<br />

Results came quickly as shown <strong>in</strong> Tables 1 and 2.<br />

From export<strong>in</strong>g no wheat at all <strong>in</strong> 1890, the State<br />

grew to be a substantial exporter as early as 1910.<br />

Thereafter production grew very rapidly, although<br />

labour shortages dur<strong>in</strong>g World War I slowed the<br />

rate <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>crease. The first class land – the open<br />

woodlands <strong>of</strong> the wheatbelt valleys – were<br />

relatively easy to clear (by axe at about 4 to<br />

5 acres a week per man), and enterpris<strong>in</strong>g people<br />

quickly developed skills <strong>in</strong> clear<strong>in</strong>g, burn<strong>in</strong>g, rak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and roll<strong>in</strong>g to hasten the process <strong>of</strong> establishment.<br />

Table 2: Expansion <strong>in</strong> gra<strong>in</strong> production 1890-1930 (Source: Burvill 1979b, p.43)<br />

Area <strong>of</strong> land cleared<br />

(m Ha)<br />

Area <strong>of</strong> land seeded<br />

for gra<strong>in</strong> (m Ha)<br />

Wheat Production<br />

(m tonnes)<br />

1890 0.05 0.014 0.013<br />

1900 0.49 0.03 0.021<br />

1910 2.1 0.24 0.16<br />

1915 n.a. 0.70 0.50<br />

1920 3.1 0.52 0.33<br />

1930 5.6 1.60 1.46<br />

– 3 –