Through the Eras

Edward Bleiberg ed., Ancient Egypt (2675-332 ... - The Fellowship

Edward Bleiberg ed., Ancient Egypt (2675-332 ... - The Fellowship

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

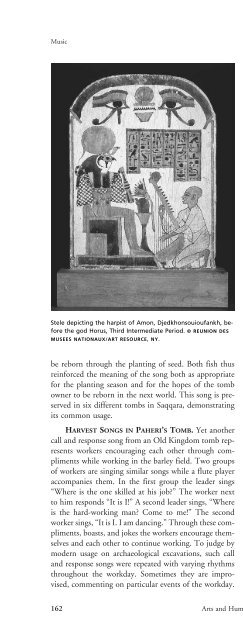

MusicThe harvest song in <strong>the</strong> tomb of Paheri is explicitly labeleda “part song.” The carving shows eight men harvestingbarley with sickles while <strong>the</strong>y sing. The first twolines describe <strong>the</strong> day, emphasizing that it is cool becauseof <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn breeze. The third and fourth lines emphasizethat <strong>the</strong> workers and nature both cooperate tomake <strong>the</strong> harvest go smoothly. Again this song depictsan ideal world where both workers and nature cooperateto ensure food for <strong>the</strong> deceased. It is not possible toknow whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> song was actually sung or only expresses<strong>the</strong> deceased tomb owner’s wishes.Stele depicting <strong>the</strong> harpist of Amon, Djedkhonsouioufankh, before<strong>the</strong> god Horus, Third Intermediate Period. © REUNION DESMUSEES NATIONAUX/ART RESOURCE, NY.be reborn through <strong>the</strong> planting of seed. Both fish thusreinforced <strong>the</strong> meaning of <strong>the</strong> song both as appropriatefor <strong>the</strong> planting season and for <strong>the</strong> hopes of <strong>the</strong> tombowner to be reborn in <strong>the</strong> next world. This song is preservedin six different tombs in Saqqara, demonstratingits common usage.HARVEST SONGS IN PAHERI’S TOMB. Yet ano<strong>the</strong>rcall and response song from an Old Kingdom tomb representsworkers encouraging each o<strong>the</strong>r through complimentswhile working in <strong>the</strong> barley field. Two groupsof workers are singing similar songs while a flute playeraccompanies <strong>the</strong>m. In <strong>the</strong> first group <strong>the</strong> leader sings“Where is <strong>the</strong> one skilled at his job?” The worker nextto him responds “It is I!” A second leader sings, “Whereis <strong>the</strong> hard-working man? Come to me!” The secondworker sings, “It is I. I am dancing.” <strong>Through</strong> <strong>the</strong>se compliments,boasts, and jokes <strong>the</strong> workers encourage <strong>the</strong>mselvesand each o<strong>the</strong>r to continue working. To judge bymodern usage on archaeological excavations, such calland response songs were repeated with varying rhythmsthroughout <strong>the</strong> workday. Sometimes <strong>the</strong>y are improvised,commenting on particular events of <strong>the</strong> workday.PLOWING AND HOEING SONGS. The plowing andhoeing songs are known from two New Kingdom tombsin Upper Egypt. The words of <strong>the</strong> songs seem to divideinto call and response sequences. The layout of <strong>the</strong> textand <strong>the</strong> accompanying illustrations make it a little difficultto determine <strong>the</strong> correct order of <strong>the</strong> verses. The reliefcarving shows four men dragging <strong>the</strong> plow—a jobnormally performed by oxen—an old man steadying <strong>the</strong>plow, and a young man sowing seed. All of <strong>the</strong> figuresface left. Fur<strong>the</strong>r to <strong>the</strong> left are four figures hoeing, <strong>the</strong>next step in <strong>the</strong> process of planting <strong>the</strong> seed. These fourhoeing figures face right. The words of <strong>the</strong> song appeardirectly above each group of figures. Egyptian hieroglyphicwriting can also face ei<strong>the</strong>r left or right and canalso begin on <strong>the</strong> right side going to <strong>the</strong> left or vice versa,unlike English writing, which can only begin on <strong>the</strong> leftand run to <strong>the</strong> right. It is thus easy to associate <strong>the</strong> linesof text with <strong>the</strong> proper group of figures because of thischaracteristic of Egyptian writing. The order of <strong>the</strong> lines,however, is unclear. It might be that <strong>the</strong> songs were anendless sequence of call and response so <strong>the</strong> slight confusionin <strong>the</strong> layout of <strong>the</strong> words might be a reflectionof <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong>se songs have no real beginning orend. These songs emphasize <strong>the</strong> positive and show <strong>the</strong>stake that <strong>the</strong> workers have in <strong>the</strong> success of <strong>the</strong> crop,even though <strong>the</strong>y work for a nobleman. The secondplowing song in <strong>the</strong> tomb of Paheri is written above agroup of workers sowing seed and plowing with oxen.A leader stands behind one of <strong>the</strong> plows with his owncolumns of text arranged near him. The arrangement oftext and image here is clearer to modern eyes. The leadersings, “Hurry, <strong>the</strong> front guides <strong>the</strong> cattle. Look! Themayor stands watching.” The three men and <strong>the</strong> boynear <strong>the</strong> cattle reply, “A beautiful day is a cool one when<strong>the</strong> cattle drag (<strong>the</strong> plow). The sky does our desire whilewe work for <strong>the</strong> nobleman.” Such a song reveals <strong>the</strong> mainpurpose for depicting <strong>the</strong>se scenes in a tomb in <strong>the</strong> firstplace; by depicting <strong>the</strong> sequence of growing crops andeager workers, <strong>the</strong> deceased ensures that he will have adequatefood supplies in <strong>the</strong> next world.162 Arts and Humanities <strong>Through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Eras</strong>: Ancient Egypt (2675 B.C.E.–332 B.C.E.)