Through the Eras

Edward Bleiberg ed., Ancient Egypt (2675-332 ... - The Fellowship

Edward Bleiberg ed., Ancient Egypt (2675-332 ... - The Fellowship

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

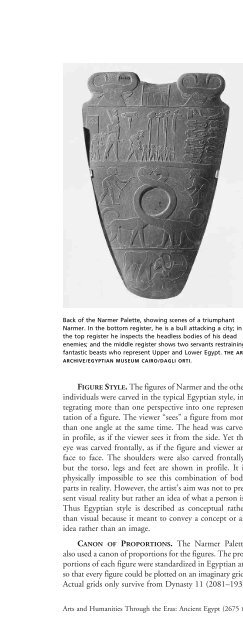

Visual ArtsBack of <strong>the</strong> Narmer Palette, showing scenes of a triumphantNarmer. In <strong>the</strong> bottom register, he is a bull attacking a city; in<strong>the</strong> top register he inspects <strong>the</strong> headless bodies of his deadenemies; and <strong>the</strong> middle register shows two servants restrainingfantastic beasts who represent Upper and Lower Egypt. THE ARTARCHIVE/EGYPTIAN MUSEUM CAIRO/DAGLI ORTI.Front of <strong>the</strong> Narmer Palette, showing Narmer with upraisedmace, defeating an enemy. This is a pose of <strong>the</strong> king whichbecame traditional in Egyptian art. THE ART ARCHIVE/EGYPTIANMUSEUM CAIRO/DAGLI ORTI.FIGURE STYLE. The figures of Narmer and <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rindividuals were carved in <strong>the</strong> typical Egyptian style, integratingmore than one perspective into one representationof a figure. The viewer “sees” a figure from morethan one angle at <strong>the</strong> same time. The head was carvedin profile, as if <strong>the</strong> viewer sees it from <strong>the</strong> side. Yet <strong>the</strong>eye was carved frontally, as if <strong>the</strong> figure and viewer areface to face. The shoulders were also carved frontally,but <strong>the</strong> torso, legs and feet are shown in profile. It isphysically impossible to see this combination of bodyparts in reality. However, <strong>the</strong> artist’s aim was not to presentvisual reality but ra<strong>the</strong>r an idea of what a person is.Thus Egyptian style is described as conceptual ra<strong>the</strong>rthan visual because it meant to convey a concept or anidea ra<strong>the</strong>r than an image.CANON OF PROPORTIONS. The Narmer Palettealso used a canon of proportions for <strong>the</strong> figures. The proportionsof each figure were standardized in Egyptian artso that every figure could be plotted on an imaginary grid.Actual grids only survive from Dynasty 11 (2081–1938B.C.E.) and later. Yet this figure has proportions similarto later representations. In a standing figure, such asNarmer found on <strong>the</strong> obverse, <strong>the</strong> grid would have containedeighteen equal units from <strong>the</strong> top of <strong>the</strong> head to<strong>the</strong> bottom of <strong>the</strong> foot. Particular body parts were <strong>the</strong>nplotted on <strong>the</strong> grid in a regular way. Counting from <strong>the</strong>bottom of <strong>the</strong> representation, <strong>the</strong> knee fell on grid linesix, <strong>the</strong> lower buttocks on line nine, <strong>the</strong> small of <strong>the</strong> backon line eleven, <strong>the</strong> elbow on line twelve, and <strong>the</strong> junctionof <strong>the</strong> neck and shoulders on line sixteen. The hairlinewas on line eighteen. The same ratio of body partswould have applied to Narmer’s standard bearer. The individualunits would have been smaller in this case since<strong>the</strong> overall figure is about one-quarter <strong>the</strong> size of Narmer.This standardized ratio of body parts gave uniformity toEgyptian representations of people. Seated representationsused a grid of 14 squares.HIERATIC SCALE. Though individual bodies all hadsimilar proportions, <strong>the</strong> scale of figures varied widelyeven within one register. On <strong>the</strong> reverse of <strong>the</strong> paletteArts and Humanities <strong>Through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Eras</strong>: Ancient Egypt (2675 B.C.E.–332 B.C.E.) 275