Through the Eras

Edward Bleiberg ed., Ancient Egypt (2675-332 ... - The Fellowship

Edward Bleiberg ed., Ancient Egypt (2675-332 ... - The Fellowship

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

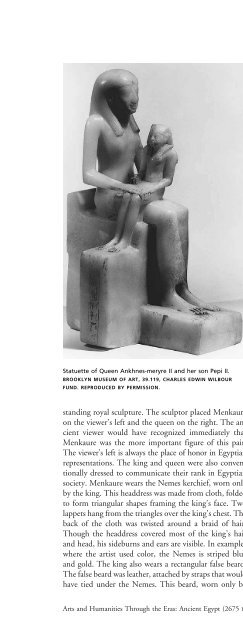

Visual ArtsStatuette of Queen Ankhnes-meryre II and her son Pepi II.BROOKLYN MUSEUM OF ART, 39.119, CHARLES EDWIN WILBOURFUND. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.standing royal sculpture. The sculptor placed Menkaureon <strong>the</strong> viewer’s left and <strong>the</strong> queen on <strong>the</strong> right. The ancientviewer would have recognized immediately thatMenkaure was <strong>the</strong> more important figure of this pair.The viewer’s left is always <strong>the</strong> place of honor in Egyptianrepresentations. The king and queen were also conventionallydressed to communicate <strong>the</strong>ir rank in Egyptiansociety. Menkaure wears <strong>the</strong> Nemes kerchief, worn onlyby <strong>the</strong> king. This headdress was made from cloth, foldedto form triangular shapes framing <strong>the</strong> king’s face. Twolappets hang from <strong>the</strong> triangles over <strong>the</strong> king’s chest. Theback of <strong>the</strong> cloth was twisted around a braid of hair.Though <strong>the</strong> headdress covered most of <strong>the</strong> king’s hairand head, his sideburns and ears are visible. In exampleswhere <strong>the</strong> artist used color, <strong>the</strong> Nemes is striped blueand gold. The king also wears a rectangular false beard.The false beard was lea<strong>the</strong>r, attached by straps that wouldhave tied under <strong>the</strong> Nemes. This beard, worn only by<strong>the</strong> king, contrasts with <strong>the</strong> longer beard that ended inan upward twist worn only by <strong>the</strong> gods. The king’s chestis bare. He wears a distinctive kilt called <strong>the</strong> shendjet,worn only by kings. The kilt features a belt and a flapthat was placed centrally between his legs. The king holdsa cylinder in each hand, usually identified as a documentcase. The case held <strong>the</strong> deed to Egypt, thought to be in<strong>the</strong> king’s possession. This statue also shows some conventionsof representing <strong>the</strong> male figure used for bothnobles and kings. The king strides forward on his leftleg, a pose typical for all standing, male Egyptian statues.The traces of red paint on <strong>the</strong> king’s ears, face, andneck show that <strong>the</strong> skin was originally painted red-ochre.This was <strong>the</strong> conventional male skin color in statuary,probably associating <strong>the</strong> deceased king or nobleman with<strong>the</strong> sun god Re. The statue of Queen Kha-merer-nebuII also exhibits <strong>the</strong> conventions for presenting women inEgyptian sculpture. Unlike kings, queens did not have<strong>the</strong>ir own conventions separate from o<strong>the</strong>r noblewomen.The queen’s wig is divided into three hanks, two drapedover her shoulders and one flowing down her back.There is a central part. The queen’s natural hair is visibleon her forehead and at <strong>the</strong> sideburns, ano<strong>the</strong>r commonconvention. The queen wears a long, form-fittingdress. The fabric appears to be stretched so tightly thatit reveals her breasts, navel, <strong>the</strong> pubic triangle, and knees.Yet <strong>the</strong> length is quite modest with a hem visible justabove <strong>the</strong> ankles. The queen’s arms are arranged conventionallywith one arm passing across <strong>the</strong> back of <strong>the</strong>king and <strong>the</strong> hand appearing at his waist. The queen’so<strong>the</strong>r hand passes across her own abdomen and rests on<strong>the</strong> king’s arm. This pose indicated <strong>the</strong> queen’s dependenceon <strong>the</strong> king for her position in society. In pairstatues that show men who were dependent upon <strong>the</strong>irwives for <strong>the</strong>ir status, <strong>the</strong> men embrace <strong>the</strong> women.STYLE AND MOTION. The conventions of Egyptianart make it easy to stress <strong>the</strong> similarity of Egyptian sculpturesto each o<strong>the</strong>r in <strong>the</strong> Old Kingdom. Yet details of<strong>the</strong> style of sculptures such as <strong>the</strong> Menkaure statue oftenmake it possible to identify specific royal figures suchas <strong>the</strong> king. All of his sculptures show distinctive facialfeatures. His face has full cheeks. His eyes bulge slightly.The chin is knobby while <strong>the</strong> nose is bulbous. His wiferesembles him, probably because <strong>the</strong> king’s face in anyreign became <strong>the</strong> ideal of beauty. In almost every period,everyone seems to resemble <strong>the</strong> reigning king. Ano<strong>the</strong>raspect of style that remained constant through much ofOld Kingdom art was <strong>the</strong> purposeful avoidance of portrayingmotion. Unlike ancient Greek sculptors, Egyptiansculptors aimed for a timelessness that excluded <strong>the</strong>transience of motion. Thus even though Menkaure andArts and Humanities <strong>Through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Eras</strong>: Ancient Egypt (2675 B.C.E.–332 B.C.E.) 283