Through the Eras

Edward Bleiberg ed., Ancient Egypt (2675-332 ... - The Fellowship

Edward Bleiberg ed., Ancient Egypt (2675-332 ... - The Fellowship

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

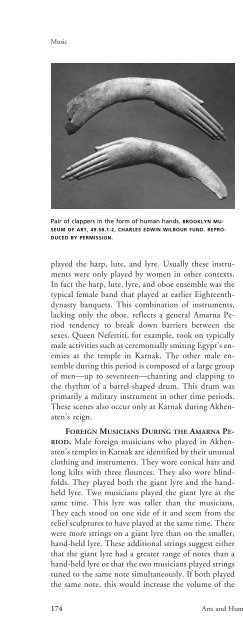

Musicsound. These musicians and <strong>the</strong>ir instrument wereunique to <strong>the</strong> Karnak temples of <strong>the</strong> Amarna period.Even <strong>the</strong> tombs of this period did not depict <strong>the</strong> giantlyre.Pair of clappers in <strong>the</strong> form of human hands. BROOKLYN MU-SEUM OF ART, 49.58.1-2, CHARLES EDWIN WILBOUR FUND. REPRO-DUCED BY PERMISSION.played <strong>the</strong> harp, lute, and lyre. Usually <strong>the</strong>se instrumentswere only played by women in o<strong>the</strong>r contexts.In fact <strong>the</strong> harp, lute, lyre, and oboe ensemble was <strong>the</strong>typical female band that played at earlier Eighteenthdynastybanquets. This combination of instruments,lacking only <strong>the</strong> oboe, reflects a general Amarna Periodtendency to break down barriers between <strong>the</strong>sexes. Queen Nefertiti, for example, took on typicallymale activities such as ceremonially smiting Egypt’s enemiesat <strong>the</strong> temple in Karnak. The o<strong>the</strong>r male ensembleduring this period is composed of a large groupof men—up to seventeen—chanting and clapping to<strong>the</strong> rhythm of a barrel-shaped drum. This drum wasprimarily a military instrument in o<strong>the</strong>r time periods.These scenes also occur only at Karnak during Akhenaten’sreign.FOREIGN MUSICIANS DURING THE AMARNA PE-RIOD. Male foreign musicians who played in Akhenaten’stemples in Karnak are identified by <strong>the</strong>ir unusualclothing and instruments. They wore conical hats andlong kilts with three flounces. They also wore blindfolds.They played both <strong>the</strong> giant lyre and <strong>the</strong> handheldlyre. Two musicians played <strong>the</strong> giant lyre at <strong>the</strong>same time. This lyre was taller than <strong>the</strong> musicians.They each stood on one side of it and seem from <strong>the</strong>relief sculptures to have played at <strong>the</strong> same time. Therewere more strings on a giant lyre than on <strong>the</strong> smaller,hand-held lyre. These additional strings suggest ei<strong>the</strong>rthat <strong>the</strong> giant lyre had a greater range of notes than ahand-held lyre or that <strong>the</strong> two musicians played stringstuned to <strong>the</strong> same note simultaneously. If both played<strong>the</strong> same note, this would increase <strong>the</strong> volume of <strong>the</strong>MUSIC IN THE CULT OF THE ATEN. The cult of<strong>the</strong> Aten, Akhenaten’s new religion, included music in<strong>the</strong> palace that honored <strong>the</strong> king as <strong>the</strong> earthly embodimentof <strong>the</strong> god. In <strong>the</strong> “Great Hymn to <strong>the</strong> Aten” <strong>the</strong>author made a specific connection between offeringfood to <strong>the</strong> Aten and music. Food offerings were <strong>the</strong>god’s meal. The god consumed <strong>the</strong> spirit of <strong>the</strong> foodwhile priests or even <strong>the</strong> royal family acting as priestsconsumed <strong>the</strong> physical food. While everyone ate, musicplayed. The relief sculptures from <strong>the</strong> temples at Karnaksuggest that lyres and even lutes were included in<strong>the</strong>se offering ceremonies in addition to <strong>the</strong> more traditionalsistra played throughout Egyptian history duringritual chanting.SOURCESLisa Manniche, Music and Musicians in Ancient Egypt (London:British Museum Press, 1991).THE BLIND SOLO HARPIST ANDHIS SONGMUSICAL GENRE AND ARTISTIC CONVENTION. Asearly as 1768 when James Bruce discovered <strong>the</strong> tomb ofRamesses III, Westerners have been aware of <strong>the</strong> idea of<strong>the</strong> blind harpist in Egyptian art. Bruce discovered twoimages of a blind harpist who sang about death in <strong>the</strong>tomb. Bruce had discovered what proved to be a verycommon <strong>the</strong>me in Egyptian art. At least 47 tombs in<strong>the</strong> Theban necropolis depict blind harp players. Thismotif decorated tombs of nobles and royalty. The blindharpist entertained at banquets but sang of death andlife after death. It was only in <strong>the</strong> mid-twentieth centurythat M. Lich<strong>the</strong>im conducted a full study of <strong>the</strong> blindharpists’ songs. The songs reveal <strong>the</strong> history of Egyptianattitudes toward death and <strong>the</strong> afterlife, although <strong>the</strong>convention of <strong>the</strong> blind or blindfolded harpist remainsan intriguing mystery.EARLIEST BLIND HARPISTS’ SONGS. The blindharpists’ songs were carved on tomb walls and on stelaein <strong>the</strong> Middle Kingdom and <strong>the</strong> New Kingdom.Their lyrics discuss <strong>the</strong> nature of death and <strong>the</strong> afterlifebut are not necessarily part of <strong>the</strong> funeral ritual.Because <strong>the</strong>ir purpose was contemplative ra<strong>the</strong>r thanritual words to effect <strong>the</strong> transformation from thisworld to <strong>the</strong> next, <strong>the</strong> authors of <strong>the</strong>se lyrics contem-174 Arts and Humanities <strong>Through</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Eras</strong>: Ancient Egypt (2675 B.C.E.–332 B.C.E.)