Linking Culture and the Environment

Linking Culture and the Environment

Linking Culture and the Environment

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

24 Recreation Ecology in Sustainable Tourism <strong>and</strong> Ecotourism<br />

<strong>and</strong> soil erosion (Wilson <strong>and</strong> Seney, 1994). The noise associated with motorized<br />

activities may displace animals from larger areas than human-powered<br />

types of recreation (Knight <strong>and</strong> Gutzwiller, 1995).<br />

Impacts may occur wherever visitor activities are concentrated: on trails or<br />

campsites, along riverbanks <strong>and</strong> lakeshores, <strong>and</strong> at attraction features such as<br />

waterfalls, coral reefs or wildlife viewing areas. Visitor use is typically distributed<br />

unevenly within protected areas, with limited areas of concentrated activity,<br />

larger areas of dispersed activity <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> majority of areas with limited or<br />

no activity (Cole, 1987; Henry, 1992). Impact may be distributed as linear disturbance<br />

along trail corridors, which in turn connect nodes of disturbance at<br />

recreation <strong>and</strong> attraction sites (Manning, 1979). At <strong>the</strong> local scale, impacts are<br />

also unevenly distributed within recreation sites or along trail corridors, reflecting<br />

differential amounts of use or environmental durability, respectively.<br />

The influence of environmental <strong>and</strong> use-related factors<br />

Differences in environmental attributes may modify <strong>the</strong> type <strong>and</strong> extent of<br />

visitor impacts. For example, <strong>the</strong> flexible stems <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r morphological<br />

characteristics of grasses make <strong>the</strong>m far more resistant to trampling than <strong>the</strong><br />

rigid stems of many broad-leafed herbs (Liddle, 1997). Differences in plant<br />

morphology <strong>and</strong> environmental conditions also create substantial variation<br />

in <strong>the</strong> ability of plants to recover following disturbance. Soil moisture <strong>and</strong><br />

nutrients, growth rates <strong>and</strong> length of growing season are o<strong>the</strong>r important<br />

factors that influence recovery rates. Similarly, soil types <strong>and</strong> associated<br />

properties vary in <strong>the</strong>ir susceptibility to compaction, erosion <strong>and</strong> muddiness<br />

(Leung <strong>and</strong> Marion, 1996; Hammitt <strong>and</strong> Cole, 1998).<br />

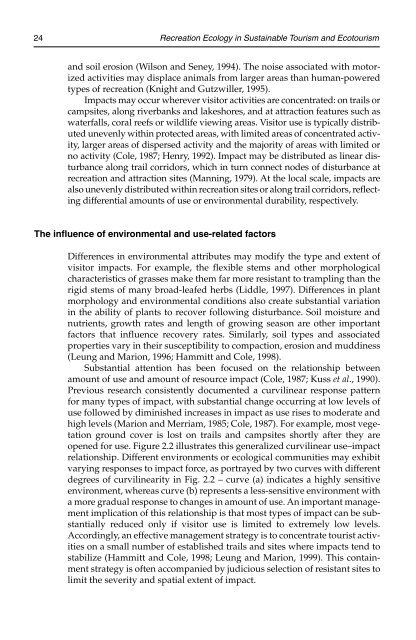

Substantial attention has been focused on <strong>the</strong> relationship between<br />

amount of use <strong>and</strong> amount of resource impact (Cole, 1987; Kuss et al., 1990).<br />

Previous research consistently documented a curvilinear response pattern<br />

for many types of impact, with substantial change occurring at low levels of<br />

use followed by diminished increases in impact as use rises to moderate <strong>and</strong><br />

high levels (Marion <strong>and</strong> Merriam, 1985; Cole, 1987). For example, most vegetation<br />

ground cover is lost on trails <strong>and</strong> campsites shortly after <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

opened for use. Figure 2.2 illustrates this generalized curvilinear use–impact<br />

relationship. Different environments or ecological communities may exhibit<br />

varying responses to impact force, as portrayed by two curves with different<br />

degrees of curvilinearity in Fig. 2.2 – curve (a) indicates a highly sensitive<br />

environment, whereas curve (b) represents a less-sensitive environment with<br />

a more gradual response to changes in amount of use. An important management<br />

implication of this relationship is that most types of impact can be substantially<br />

reduced only if visitor use is limited to extremely low levels.<br />

Accordingly, an effective management strategy is to concentrate tourist activities<br />

on a small number of established trails <strong>and</strong> sites where impacts tend to<br />

stabilize (Hammitt <strong>and</strong> Cole, 1998; Leung <strong>and</strong> Marion, 1999). This containment<br />

strategy is often accompanied by judicious selection of resistant sites to<br />

limit <strong>the</strong> severity <strong>and</strong> spatial extent of impact.