Four degrees and beyond: the potential for a global ... - Amper

Four degrees and beyond: the potential for a global ... - Amper

Four degrees and beyond: the potential for a global ... - Amper

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

8 M. New et al.<br />

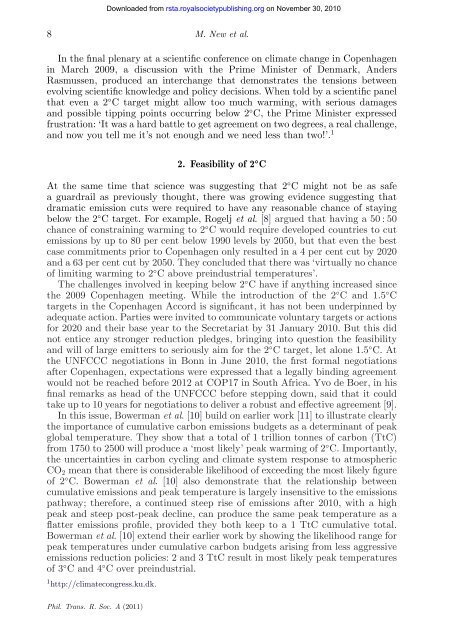

In <strong>the</strong> final plenary at a scientific conference on climate change in Copenhagen<br />

in March 2009, a discussion with <strong>the</strong> Prime Minister of Denmark, Anders<br />

Rasmussen, produced an interchange that demonstrates <strong>the</strong> tensions between<br />

evolving scientific knowledge <strong>and</strong> policy decisions. When told by a scientific panel<br />

that even a 2 ◦ C target might allow too much warming, with serious damages<br />

<strong>and</strong> possible tipping points occurring below 2 ◦ C, <strong>the</strong> Prime Minister expressed<br />

frustration: ‘It was a hard battle to get agreement on two <strong>degrees</strong>, a real challenge,<br />

<strong>and</strong> now you tell me it’s not enough <strong>and</strong> we need less than two!’. 1<br />

2. Feasibility of 2 ◦ C<br />

At <strong>the</strong> same time that science was suggesting that 2◦C might not be as safe<br />

a guardrail as previously thought, <strong>the</strong>re was growing evidence suggesting that<br />

dramatic emission cuts were required to have any reasonable chance of staying<br />

below <strong>the</strong> 2◦C target. For example, Rogelj et al. [8] argued that having a 50 : 50<br />

chance of constraining warming to 2◦C would require developed countries to cut<br />

emissions by up to 80 per cent below 1990 levels by 2050, but that even <strong>the</strong> best<br />

case commitments prior to Copenhagen only resulted in a4percentcutby2020<br />

<strong>and</strong> a 63 per cent cut by 2050. They concluded that <strong>the</strong>re was ‘virtually no chance<br />

of limiting warming to 2◦C above preindustrial temperatures’.<br />

The challenges involved in keeping below 2◦C have if anything increased since<br />

<strong>the</strong> 2009 Copenhagen meeting. While <strong>the</strong> introduction of <strong>the</strong> 2◦C <strong>and</strong> 1.5◦C targets in <strong>the</strong> Copenhagen Accord is significant, it has not been underpinned by<br />

adequate action. Parties were invited to communicate voluntary targets or actions<br />

<strong>for</strong> 2020 <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir base year to <strong>the</strong> Secretariat by 31 January 2010. But this did<br />

not entice any stronger reduction pledges, bringing into question <strong>the</strong> feasibility<br />

<strong>and</strong> will of large emitters to seriously aim <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> 2◦C target, let alone 1.5◦C. At<br />

<strong>the</strong> UNFCCC negotiations in Bonn in June 2010, <strong>the</strong> first <strong>for</strong>mal negotiations<br />

after Copenhagen, expectations were expressed that a legally binding agreement<br />

would not be reached be<strong>for</strong>e 2012 at COP17 in South Africa. Yvo de Boer, in his<br />

final remarks as head of <strong>the</strong> UNFCCC be<strong>for</strong>e stepping down, said that it could<br />

take up to 10 years <strong>for</strong> negotiations to deliver a robust <strong>and</strong> effective agreement [9].<br />

In this issue, Bowerman et al. [10] build on earlier work [11] to illustrate clearly<br />

<strong>the</strong> importance of cumulative carbon emissions budgets as a determinant of peak<br />

<strong>global</strong> temperature. They show that a total of 1 trillion tonnes of carbon (TtC)<br />

from 1750 to 2500 will produce a ‘most likely’ peak warming of 2◦C. Importantly,<br />

<strong>the</strong> uncertainties in carbon cycling <strong>and</strong> climate system response to atmospheric<br />

CO2 mean that <strong>the</strong>re is considerable likelihood of exceeding <strong>the</strong> most likely figure<br />

of 2◦C. Bowerman et al. [10] also demonstrate that <strong>the</strong> relationship between<br />

cumulative emissions <strong>and</strong> peak temperature is largely insensitive to <strong>the</strong> emissions<br />

pathway; <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, a continued steep rise of emissions after 2010, with a high<br />

peak <strong>and</strong> steep post-peak decline, can produce <strong>the</strong> same peak temperature as a<br />

flatter emissions profile, provided <strong>the</strong>y both keep to a 1 TtC cumulative total.<br />

Bowerman et al. [10] extend <strong>the</strong>ir earlier work by showing <strong>the</strong> likelihood range <strong>for</strong><br />

peak temperatures under cumulative carbon budgets arising from less aggressive<br />

emissions reduction policies: 2 <strong>and</strong> 3 TtC result in most likely peak temperatures<br />

of 3◦C <strong>and</strong> 4◦C over preindustrial.<br />

1http://climatecongress.ku.dk. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A (2011)<br />

Downloaded from<br />

rsta.royalsocietypublishing.org on November 30, 2010