Kerala 2005 - of Planning Commission

Kerala 2005 - of Planning Commission

Kerala 2005 - of Planning Commission

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

CHAPTER 7<br />

RECKONING CAUTION: EDUCATED UNEMPLOYMENT AND GENDER UNFREEDOM<br />

105<br />

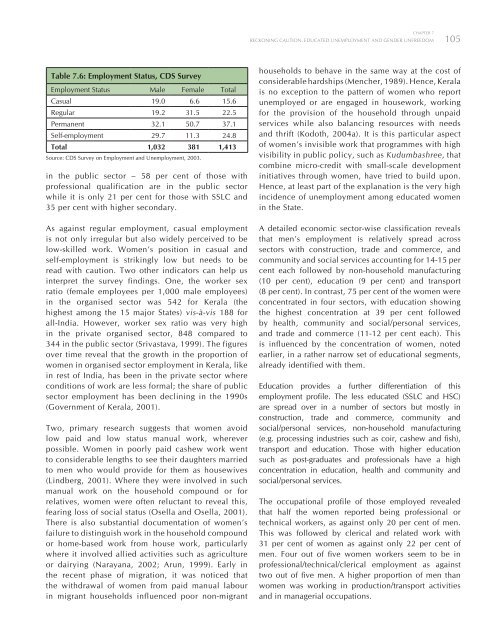

Table 7.6: Employment Status, CDS Survey<br />

Employment Status Male Female Total<br />

Casual 19.0 6.6 15.6<br />

Regular 19.2 31.5 22.5<br />

Permanent 32.1 50.7 37.1<br />

Self-employment 29.7 11.3 24.8<br />

Total 1,032 381 1,413<br />

Source: CDS Survey on Employment and Unemployment, 2003.<br />

in the public sector – 58 per cent <strong>of</strong> those with<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essional qualification are in the public sector<br />

while it is only 21 per cent for those with SSLC and<br />

35 per cent with higher secondary.<br />

As against regular employment, casual employment<br />

is not only irregular but also widely perceived to be<br />

low-skilled work. Women’s position in casual and<br />

self-employment is strikingly low but needs to be<br />

read with caution. Two other indicators can help us<br />

interpret the survey findings. One, the worker sex<br />

ratio (female employees per 1,000 male employees)<br />

in the organised sector was 542 for <strong>Kerala</strong> (the<br />

highest among the 15 major States) vis-à-vis 188 for<br />

all-India. However, worker sex ratio was very high<br />

in the private organised sector, 848 compared to<br />

344 in the public sector (Srivastava, 1999). The figures<br />

over time reveal that the growth in the proportion <strong>of</strong><br />

women in organised sector employment in <strong>Kerala</strong>, like<br />

in rest <strong>of</strong> India, has been in the private sector where<br />

conditions <strong>of</strong> work are less formal; the share <strong>of</strong> public<br />

sector employment has been declining in the 1990s<br />

(Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kerala</strong>, 2001).<br />

Two, primary research suggests that women avoid<br />

low paid and low status manual work, wherever<br />

possible. Women in poorly paid cashew work went<br />

to considerable lengths to see their daughters married<br />

to men who would provide for them as housewives<br />

(Lindberg, 2001). Where they were involved in such<br />

manual work on the household compound or for<br />

relatives, women were <strong>of</strong>ten reluctant to reveal this,<br />

fearing loss <strong>of</strong> social status (Osella and Osella, 2001).<br />

There is also substantial documentation <strong>of</strong> women’s<br />

failure to distinguish work in the household compound<br />

or home-based work from house work, particularly<br />

where it involved allied activities such as agriculture<br />

or dairying (Narayana, 2002; Arun, 1999). Early in<br />

the recent phase <strong>of</strong> migration, it was noticed that<br />

the withdrawal <strong>of</strong> women from paid manual labour<br />

in migrant households influenced poor non-migrant<br />

households to behave in the same way at the cost <strong>of</strong><br />

considerable hardships (Mencher, 1989). Hence, <strong>Kerala</strong><br />

is no exception to the pattern <strong>of</strong> women who report<br />

unemployed or are engaged in housework, working<br />

for the provision <strong>of</strong> the household through unpaid<br />

services while also balancing resources with needs<br />

and thrift (Kodoth, 2004a). It is this particular aspect<br />

<strong>of</strong> women’s invisible work that programmes with high<br />

visibility in public policy, such as Kudumbashree, that<br />

combine micro-credit with small-scale development<br />

initiatives through women, have tried to build upon.<br />

Hence, at least part <strong>of</strong> the explanation is the very high<br />

incidence <strong>of</strong> unemployment among educated women<br />

in the State.<br />

A detailed economic sector-wise classification reveals<br />

that men’s employment is relatively spread across<br />

sectors with construction, trade and commerce, and<br />

community and social services accounting for 14-15 per<br />

cent each followed by non-household manufacturing<br />

(10 per cent), education (9 per cent) and transport<br />

(8 per cent). In contrast, 75 per cent <strong>of</strong> the women were<br />

concentrated in four sectors, with education showing<br />

the highest concentration at 39 per cent followed<br />

by health, community and social/personal services,<br />

and trade and commerce (11-12 per cent each). This<br />

is influenced by the concentration <strong>of</strong> women, noted<br />

earlier, in a rather narrow set <strong>of</strong> educational segments,<br />

already identified with them.<br />

Education provides a further differentiation <strong>of</strong> this<br />

employment pr<strong>of</strong>ile. The less educated (SSLC and HSC)<br />

are spread over in a number <strong>of</strong> sectors but mostly in<br />

construction, trade and commerce, community and<br />

social/personal services, non-household manufacturing<br />

(e.g. processing industries such as coir, cashew and fish),<br />

transport and education. Those with higher education<br />

such as post-graduates and pr<strong>of</strong>essionals have a high<br />

concentration in education, health and community and<br />

social/personal services.<br />

The occupational pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> those employed revealed<br />

that half the women reported being pr<strong>of</strong>essional or<br />

technical workers, as against only 20 per cent <strong>of</strong> men.<br />

This was followed by clerical and related work with<br />

31 per cent <strong>of</strong> women as against only 22 per cent <strong>of</strong><br />

men. Four out <strong>of</strong> five women workers seem to be in<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essional/technical/clerical employment as against<br />

two out <strong>of</strong> five men. A higher proportion <strong>of</strong> men than<br />

women was working in production/transport activities<br />

and in managerial occupations.