Kerala 2005 - of Planning Commission

Kerala 2005 - of Planning Commission

Kerala 2005 - of Planning Commission

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

136<br />

maximum result within the given economic and social<br />

parameters. The long-run is usually referred to a timehorizon<br />

during which increases in productive capacity is<br />

taken into account through investment as well as changes<br />

in institutional variables. Such a distinction should not also<br />

be taken as a water-tight compartment. In reality, there<br />

are times and areas in which the short and the long-run<br />

intersect. However such a distinction is analytically useful<br />

in spelling out some policy options.<br />

Let us take the short term first. As we have been<br />

emphasising, unemployment, mainly educated<br />

unemployment, is the biggest socio-economic problem<br />

in <strong>Kerala</strong>. As seen in Chapter 6, the quality <strong>of</strong> education<br />

is crucial if the State is to convert this pool <strong>of</strong> educated<br />

labour into one which could be employable both within<br />

and outside its labour market. International migration has<br />

provided a useful outlet for this pool <strong>of</strong> labour in <strong>Kerala</strong>.<br />

Until the late 1990s, two-thirds <strong>of</strong> emigrants had only<br />

less than 10 years <strong>of</strong> schooling. This was because there<br />

was a high demand for unskilled labour in such manual<br />

work as in construction, maintenance, trading, etc. With<br />

the end <strong>of</strong> the construction boom in Gulf countries, the<br />

demand pattern has been undergoing a significant change.<br />

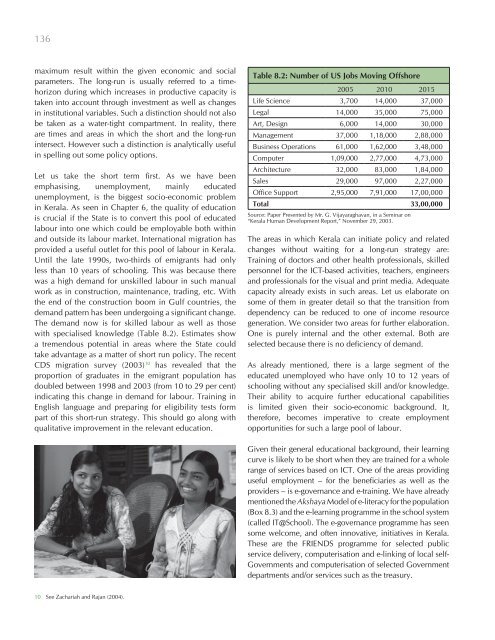

The demand now is for skilled labour as well as those<br />

with specialised knowledge (Table 8.2). Estimates show<br />

a tremendous potential in areas where the State could<br />

take advantage as a matter <strong>of</strong> short run policy. The recent<br />

CDS migration survey (2003) 10 has revealed that the<br />

proportion <strong>of</strong> graduates in the emigrant population has<br />

doubled between 1998 and 2003 (from 10 to 29 per cent)<br />

indicating this change in demand for labour. Training in<br />

English language and preparing for eligibility tests form<br />

part <strong>of</strong> this short-run strategy. This should go along with<br />

qualitative improvement in the relevant education.<br />

Table 8.2: Number <strong>of</strong> US Jobs Moving Offshore<br />

<strong>2005</strong> 2010 2015<br />

Life Science 3,700 14,000 37,000<br />

Legal 14,000 35,000 75,000<br />

Art, Design 6,000 14,000 30,000<br />

Management 37,000 1,18,000 2,88,000<br />

Business Operations 61,000 1,62,000 3,48,000<br />

Computer 1,09,000 2,77,000 4,73,000<br />

Architecture 32,000 83,000 1,84,000<br />

Sales 29,000 97,000 2,27,000<br />

Office Support 2,95,000 7,91,000 17,00,000<br />

Total 33,00,000<br />

Source: Paper Presented by Mr. G. Vijayaraghavan, in a Seminar on<br />

“<strong>Kerala</strong> Human Development Report,” November 29, 2003.<br />

The areas in which <strong>Kerala</strong> can initiate policy and related<br />

changes without waiting for a long-run strategy are:<br />

Training <strong>of</strong> doctors and other health pr<strong>of</strong>essionals, skilled<br />

personnel for the ICT-based activities, teachers, engineers<br />

and pr<strong>of</strong>essionals for the visual and print media. Adequate<br />

capacity already exists in such areas. Let us elaborate on<br />

some <strong>of</strong> them in greater detail so that the transition from<br />

dependency can be reduced to one <strong>of</strong> income resource<br />

generation. We consider two areas for further elaboration.<br />

One is purely internal and the other external. Both are<br />

selected because there is no deficiency <strong>of</strong> demand.<br />

As already mentioned, there is a large segment <strong>of</strong> the<br />

educated unemployed who have only 10 to 12 years <strong>of</strong><br />

schooling without any specialised skill and/or knowledge.<br />

Their ability to acquire further educational capabilities<br />

is limited given their socio-economic background. It,<br />

therefore, becomes imperative to create employment<br />

opportunities for such a large pool <strong>of</strong> labour.<br />

Given their general educational background, their learning<br />

curve is likely to be short when they are trained for a whole<br />

range <strong>of</strong> services based on ICT. One <strong>of</strong> the areas providing<br />

useful employment – for the beneficiaries as well as the<br />

providers – is e-governance and e-training. We have already<br />

mentioned the Akshaya Model <strong>of</strong> e-literacy for the population<br />

(Box 8.3) and the e-learning programme in the school system<br />

(called IT@School). The e-governance programme has seen<br />

some welcome, and <strong>of</strong>ten innovative, initiatives in <strong>Kerala</strong>.<br />

These are the FRIENDS programme for selected public<br />

service delivery, computerisation and e-linking <strong>of</strong> local self-<br />

Governments and computerisation <strong>of</strong> selected Government<br />

departments and/or services such as the treasury.<br />

10 See Zachariah and Rajan (2004).