Kerala 2005 - of Planning Commission

Kerala 2005 - of Planning Commission

Kerala 2005 - of Planning Commission

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

108<br />

An overwhelming majority (84 per cent for women and<br />

73 per cent for men) reported family and/or friends as the<br />

source <strong>of</strong> finance and this did not make any difference<br />

according to educational levels. As such the evidence<br />

does not suggest an active involvement <strong>of</strong> financial<br />

institutions in helping those who would like to generate<br />

their own employment.<br />

Most reported (75 per cent) that education helped to start<br />

self-employment and this held good irrespective <strong>of</strong> the<br />

level <strong>of</strong> education. The share was higher for those with<br />

higher educational levels.<br />

2.6 Occupational Mobility<br />

The status <strong>of</strong> employment is influenced by occupational<br />

mobility. Estimates from the NSSO for the number <strong>of</strong> usual<br />

principal status employed persons per 1,000 workers who<br />

changed their establishment <strong>of</strong> work, status/ industry <strong>of</strong><br />

work and occupation <strong>of</strong> work during last two years appear<br />

to be very unfavourable to women. In terms <strong>of</strong> status, not<br />

a single woman worker per 1,000 employed women in<br />

urban areas changed her status in this period; in terms <strong>of</strong><br />

occupation, such proportions were barely one-fifth for men<br />

in both rural and urban areas. However, the proportion<br />

<strong>of</strong> men and women changing establishments was not very<br />

dissimilar (Eapen, 2004). Hence, women are more mobile<br />

between establishments while hardly achieving any<br />

upward mobility.<br />

In this context, micro studies provide further insight.<br />

Boxes 7.2 and 7.3 indicate that greater diversification<br />

<strong>of</strong> household incomes, significant male out-migration<br />

and high levels <strong>of</strong> male occupational mobility have<br />

been associated with the confinement <strong>of</strong> women to low<br />

paying conventional occupations or their withdrawal into<br />

‘household duties’.<br />

2.7 Dimensions <strong>of</strong> Unemployment<br />

‘Unemployment rate is X per cent’ is a one-dimensional<br />

definition <strong>of</strong> unemployment i.e., those without work out<br />

<strong>of</strong> the total labour force. It refers to the ‘time’ dimension<br />

<strong>of</strong> unemployment. In the early development literature,<br />

the limitation <strong>of</strong> this definition and measurement<br />

was highlighted through the concept <strong>of</strong> ‘disguised<br />

unemployment’, i.e. those who may be spending<br />

time working but without adequate income or output.<br />

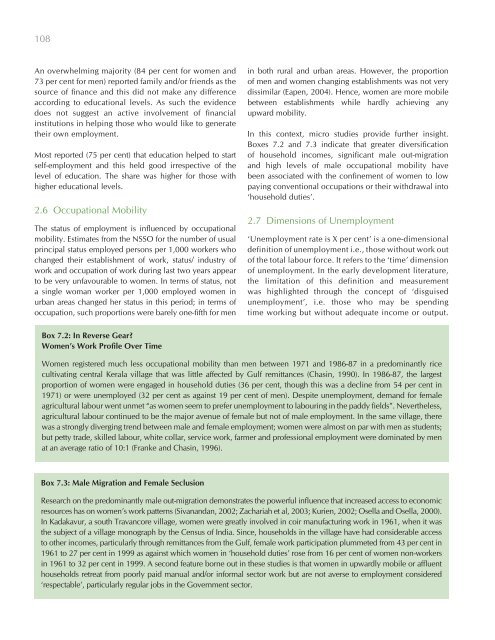

Box 7.2: In Reverse Gear?<br />

Women’s Work Pr<strong>of</strong>ile Over Time<br />

Women registered much less occupational mobility than men between 1971 and 1986-87 in a predominantly rice<br />

cultivating central <strong>Kerala</strong> village that was little affected by Gulf remittances (Chasin, 1990). In 1986-87, the largest<br />

proportion <strong>of</strong> women were engaged in household duties (36 per cent, though this was a decline from 54 per cent in<br />

1971) or were unemployed (32 per cent as against 19 per cent <strong>of</strong> men). Despite unemployment, demand for female<br />

agricultural labour went unmet “as women seem to prefer unemployment to labouring in the paddy fields”. Nevertheless,<br />

agricultural labour continued to be the major avenue <strong>of</strong> female but not <strong>of</strong> male employment. In the same village, there<br />

was a strongly diverging trend between male and female employment; women were almost on par with men as students;<br />

but petty trade, skilled labour, white collar, service work, farmer and pr<strong>of</strong>essional employment were dominated by men<br />

at an average ratio <strong>of</strong> 10:1 (Franke and Chasin, 1996).<br />

Box 7.3: Male Migration and Female Seclusion<br />

Research on the predominantly male out-migration demonstrates the powerful influence that increased access to economic<br />

resources has on women’s work patterns (Sivanandan, 2002; Zachariah et al, 2003; Kurien, 2002; Osella and Osella, 2000).<br />

In Kadakavur, a south Travancore village, women were greatly involved in coir manufacturing work in 1961, when it was<br />

the subject <strong>of</strong> a village monograph by the Census <strong>of</strong> India. Since, households in the village have had considerable access<br />

to other incomes, particularly through remittances from the Gulf, female work participation plummeted from 43 per cent in<br />

1961 to 27 per cent in 1999 as against which women in ‘household duties’ rose from 16 per cent <strong>of</strong> women non-workers<br />

in 1961 to 32 per cent in 1999. A second feature borne out in these studies is that women in upwardly mobile or affluent<br />

households retreat from poorly paid manual and/or informal sector work but are not averse to employment considered<br />

‘respectable’, particularly regular jobs in the Government sector.