- Page 1 and 2:

MUNN'S NTRODUCTION TO FERNALD/FERNA

- Page 4 and 5:

INTRODUCTION TO Psychology L. DODGE

- Page 6:

List of Figures xv Acknowledgments

- Page 9 and 10:

viii Contents Part 2 The Human Orga

- Page 11 and 12:

Contents Part 4 Learning and Inform

- Page 13 and 14:

xii Contents Part 6 Individual Diff

- Page 15 and 16:

xiv Contents Part 8 Psychology and

- Page 17 and 18:

xvi List of Figures Figure 8.1 Lana

- Page 20 and 21:

As the reader Purely will decide, t

- Page 23:

A Journey

- Page 26 and 27:

Prologue Title Topic Source /. Psyc

- Page 28 and 29: Prologue xxvii Like the response pa

- Page 30: INTRODUCTION TO Psychology

- Page 35 and 36: Background and Methods At mealtime

- Page 37 and 38: Background and Methods Figure 1.2 T

- Page 39 and 40: 10 Background and Methods 'One spri

- Page 41 and 42: 12 Background and Methods It should

- Page 43 and 44: 14 Background and Methods James and

- Page 45 and 46: 16 Background and Methods Figure 1.

- Page 47 and 48: 18 Background and Methods Figure 1.

- Page 49 and 50: 20 Background and Methods Figure 1.

- Page 51 and 52: 22 Background and Methods 'Sitting

- Page 53 and 54: 24 Background and Methods Each of t

- Page 55 and 56: 26 Background and Methods Emergence

- Page 59 and 60: 30 Background and Methods "My mothe

- Page 61 and 62: 32 Background and Methods Collectin

- Page 63 and 64: 34 Background and Methods A related

- Page 65 and 66: 36 Background and Methods Figure 2.

- Page 67 and 68: 38 Background and Methods *l was on

- Page 69 and 70: 40 Background and Methods CLINICAL

- Page 71 and 72: 42 Background and Methods Psycholog

- Page 73 and 74: Background and Methods Another trou

- Page 75 and 76: 46 Background and Methods Figure 2.

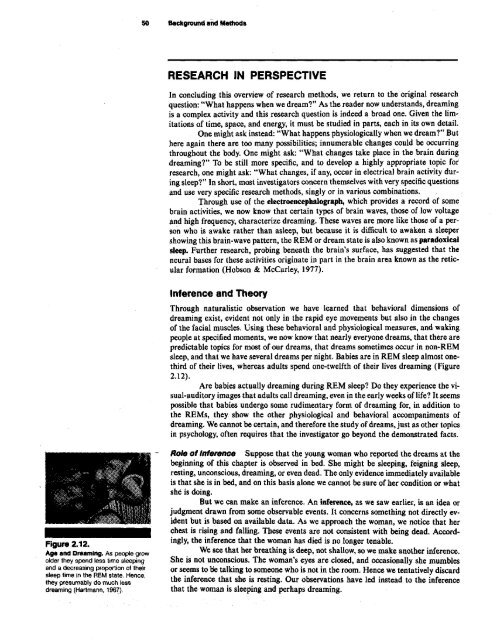

- Page 77: 48 Background and Methods When the

- Page 81 and 82: 52 Background and Methods Prior to

- Page 83 and 84: 54 Background and Methods Survey Me

- Page 89 and 90: 60 The Human Organism The study of

- Page 91 and 92: 62 The Human Organism Figure 3.4 In

- Page 93 and 94: 64 The Human Organism Figure 3.7 De

- Page 95 and 96: 66 The Human Organism The increased

- Page 97 and 98: 68 The Human Organism This totally

- Page 99 and 100: Plate 2 Eight-Week-Old Fetus. In ju

- Page 101 and 102: 70 The Human Organism Sensorimotor

- Page 103 and 104: 72 The Human Organism The deprivati

- Page 105 and 106: 74 The Human Organism Figure 3.13 I

- Page 107 and 108: 76 The Human Organism The qualifica

- Page 109 and 110: 78 The Human Organism Figure 3.15 D

- Page 111 and 112: 80 The Human Organism Figure 3.17 A

- Page 113 and 114: 82 The Human Organism Transfer Grou

- Page 115 and 116: 84 The Human Organism INDIVIDUAL DI

- Page 117 and 118: 86 The Human Organism Heredity and

- Page 120 and 121: fftgtepoiitfHf ДОИ* * L» i-'"-,

- Page 122 and 123: Physiology and Behavior 91 Figure 4

- Page 124 and 125: Physiology and Behavior 93 —f Res

- Page 126 and 127: Physiology and Behavior 95 Figure 4

- Page 128 and 129:

Physiology and Behavior 97 Receptor

- Page 130 and 131:

Physiology and Behavior 99 Motor Pr

- Page 132 and 133:

Physiology and Behavior 101 Nonsens

- Page 134 and 135:

.,••. ь • • : • ; •

- Page 136 and 137:

Physiology and Behavior 105 On this

- Page 138 and 139:

Physiology and Behavior 107 Lung He

- Page 140 and 141:

Physiology and Behavior 109 part of

- Page 142 and 143:

Physiology and Behavior 111 One fun

- Page 144 and 145:

Physiology and Behavior 113 Figure

- Page 146 and 147:

Physiology and Behavior 115 Subcort

- Page 149 and 150:

•'л§ а- 1 : '•:£•* a i'A

- Page 153 and 154:

122 Modes of Awareness In this chap

- Page 155 and 156:

124 Modes of Awareness *James Bond

- Page 157 and 158:

126 Modes of Awareness TRADITIONAL

- Page 159 and 160:

128 Modes of Awareness Figure 5.5 T

- Page 161 and 162:

130 Modes of Awareness *l knew a gu

- Page 163 and 164:

132 Modes of Awareness Figure 5.8 C

- Page 165 and 166:

Plate 6 Retinal Color Zones. This c

- Page 167 and 168:

134 Modes of Awareness whereas the

- Page 169 and 170:

136 Modes of Awareness -J- Hair Fre

- Page 171 and 172:

138 Modes of Awareness Figure 5.13

- Page 173 and 174:

140 Modes of Awareness 'I've often

- Page 175 and 176:

142 Modes of Awareness the light ea

- Page 177 and 178:

144 Modes of Awareness 5. The stimu

- Page 179 and 180:

K^^rT, •. -Y - w* 7 r< - ч. 3i>.

- Page 181 and 182:

148 Modes of Awareness The boy's ar

- Page 183 and 184:

150 Modes of Awareness Stimulus Cha

- Page 185 and 186:

152 Modes of Awareness Figure 6.3 I

- Page 187 and 188:

1S4 Modes of Awareness L \ С Figur

- Page 189 and 190:

156 Modes of Awareness MAKING AN IN

- Page 191 and 192:

158 Modes of Awareness 'When I was

- Page 193 and 194:

160 Modes of Awareness The same sor

- Page 195 and 196:

162 Modes of Awareness Figure 6.15

- Page 197 and 198:

164 Modes of Awareness Achieving an

- Page 199 and 200:

166 Modes of Awareness Altogether,

- Page 201 and 202:

168 Modes of Awareness Figure 6.19

- Page 203 and 204:

170 Modes of Awareness A most impor

- Page 205 and 206:

172 Modes of Awareness 7. An illusi

- Page 207:

,_•,„-:..&и';#&*•;,. 77:^7

- Page 210 and 211:

7 Learning as Conditioning CLASSICA

- Page 212 and 213:

Learning as Conditioning 179 Classi

- Page 214 and 215:

Learning as Conditioning 181 Consid

- Page 216 and 217:

Learning as Conditioning 183 the cl

- Page 218 and 219:

Learning as Conditioning 185 Pavlov

- Page 220 and 221:

Learning as Conditioning 187 A food

- Page 222 and 223:

Learning as Conditioning 189 hours,

- Page 224 and 225:

Learning as Conditioning 191 1,000

- Page 226 and 227:

Learning as Conditioning 193 Extern

- Page 228 and 229:

Learning as Conditioning 195 The or

- Page 230 and 231:

Learning as Conditioning 197 This v

- Page 232:

Learning as Conditioning 199 Critic

- Page 235 and 236:

202 Learning and Information Proces

- Page 237 and 238:

204 Learning and Information Proces

- Page 239 and 240:

206 Learning and Information Proces

- Page 241 and 242:

208 Learning and Information Proces

- Page 243 and 244:

210 Learning and Information Proces

- Page 245 and 246:

212 Learning and Information Proces

- Page 247 and 248:

214 Learning and Information Proces

- Page 249 and 250:

216 Learning and Information Proces

- Page 251 and 252:

218 Learning and Information Proces

- Page 253 and 254:

220 Learning and Information Proces

- Page 255 and 256:

222 Learning and Information Proces

- Page 257 and 258:

224 Learning and Information Proces

- Page 259 and 260:

226 Learning and Information Proces

- Page 261:

228 Learning and Information Proces

- Page 264 and 265:

Memory Rote Mnembiifc'fievices iMRn

- Page 266 and 267:

Memory 233 which in this case were

- Page 268 and 269:

Memory 235 Reappearance Hypothesis

- Page 270 and 271:

Memory 237 Method of Recognition If

- Page 272 and 273:

Memory 239 Images in the Sensjry Sy

- Page 274 and 275:

Memory 241 In this sense Harold Bur

- Page 276 and 277:

Memory 243 Depth of processing is n

- Page 278 and 279:

Plate 9 Structure of DNA. The disco

- Page 280 and 281:

Memory 245 Figure 9.10 Decay Theory

- Page 282 and 283:

Memory 247 Figure 9.12 Interference

- Page 284 and 285:

Memory 249 Repressive Forgetting Ou

- Page 286 and 287:

Memory 251 Type of Passage Original

- Page 288 and 289:

Memory 253 Figure 9.18 Overlearning

- Page 290 and 291:

Memory 255 Memory trace Physiologic

- Page 292 and 293:

Memory 257 10. Forgetting apparentl

- Page 294 and 295:

- " - • ~ and Instruction . p Of

- Page 296 and 297:

Learning and Instruction 261 After

- Page 298 and 299:

Learning and Instruction 263 For th

- Page 300 and 301:

Learning and Instruction 265 Figure

- Page 302 and 303:

Learning and Instruction 267 Figure

- Page 304 and 305:

Learning and Instruction 269 1. Stu

- Page 306 and 307:

Learning and Instruction 271 domain

- Page 308 and 309:

— Learning and Instruction 273 d>

- Page 310 and 311:

Learning and Instruction 275 Figure

- Page 312 and 313:

Learning and Instruction 277 Useful

- Page 314 and 315:

Learning and Instruction 279 cube,

- Page 316 and 317:

Learning and Instruction 281 10. Th

- Page 319 and 320:

d l Robin's Voyage ••-,-й . я

- Page 321 and 322:

286 Motivation and Emotion Robin's

- Page 323 and 324:

288 Motivation and Emotion Figure 1

- Page 325 and 326:

290 Motivation and Emotion Robin al

- Page 327 and 328:

292 Motivation and Emotion Species

- Page 329 and 330:

294 Motivation and Emotion Figure 1

- Page 331 and 332:

296 Motivation and Emotion Method o

- Page 333 and 334:

298 Motivation and Emotion Cellular

- Page 335 and 336:

300 MotivatiO7i and Emotion *' v

- Page 337 and 338:

302 Motivation and Emotion Figure 1

- Page 339 and 340:

304 Motivation and Emotion Social I

- Page 341 and 342:

306 Motivation and Emotion Critique

- Page 343 and 344:

308 Motivation and Emotion Figure 1

- Page 345 and 346:

310 Motivation and Emotion 3. As on

- Page 347 and 348:

Together i^lf*

- Page 349 and 350:

314 Motivation and Emotion Stephen

- Page 351 and 352:

316 Motivation and Emotion *We all

- Page 353 and 354:

318 Motivation and Emotion Figure 1

- Page 355 and 356:

320 Motivation and Emotion 'Last Sa

- Page 357 and 358:

322 Motivation and Emotion "This st

- Page 359 and 360:

324 Motivation and Emotion Figure 1

- Page 361 and 362:

326 Motivation and Emotion of neigh

- Page 363 and 364:

328 Motivation and Emotion Here aga

- Page 365 and 366:

330 Motivation and Emotion Figure 1

- Page 367 and 368:

332 Motivation and Emotion ;...•>

- Page 369 and 370:

334 Motivation and Emotion 14 Figur

- Page 371 and 372:

336 Motivation and Emotion Figure 1

- Page 373 and 374:

338 Motivation and Emotion Summary

- Page 375:

340 Motivation and Emotion Critical

- Page 378 and 379:

г -' -'-"i-i-г- • * * • -!*'

- Page 380 and 381:

METHODS OF Early Development» Со

- Page 382 and 383:

Tests and Measurement 347 Early Dev

- Page 384 and 385:

Tests and Measurement 349 Figure 13

- Page 386 and 387:

Tests and Measurement 351 1. Will y

- Page 388 and 389:

Tests and Measurement 353 General K

- Page 390 and 391:

Tests and Measurement 355 Weights H

- Page 392 and 393:

Plate11 Testing Spatial Relations A

- Page 394 and 395:

1 .•• Tests and Measurement 357

- Page 396 and 397:

Tests and Measurement 359 The pisto

- Page 398 and 399:

Tests and Measurement 361 Norm-Refe

- Page 400 and 401:

Tests and Measurement 363 Evaluatio

- Page 402 and 403:

Tests and Measurement 365 Summary M

- Page 406 and 407:

Intelligence "tiEMSOHEMENT OFINTELL

- Page 408 and 409:

Intelligence 371 Binet's Early Scal

- Page 410 and 411:

Intelligence 373 But any complex so

- Page 412 and 413:

Intelligence 375 Figure 14.8 Struct

- Page 414 and 415:

Intelligence 377 Terman and Goddard

- Page 416 and 417:

Intelligence 379 Goddard completely

- Page 418 and 419:

Intelligence 381 With regard to phy

- Page 420 and 421:

Intelligence 383 ORIGINS OF INTELLI

- Page 422 and 423:

Intelligence 385 Figure 14.16 Exami

- Page 424 and 425:

Intelligence 387 Both factors are a

- Page 426 and 427:

Intelligence 389 CD 8 6.4 6.2 60 I

- Page 428 and 429:

Intelligence 391 This commentary, f

- Page 430:

Intelligence 393 8. Surveys have sh

- Page 434 and 435:

Personality THEORY OF PSYCHOANALYSI

- Page 436 and 437:

Personality 399 Figure 15.2 Fraud i

- Page 438 and 439:

Personality 401 Figure 15.4 Imitati

- Page 440 and 441:

Personality 403 Jenny's Unconscious

- Page 442 and 443:

Personality 405 Figure 15.6 Project

- Page 444 and 445:

Personality 407 thus offers greater

- Page 446 and 447:

Personality 409 Figure 15.8 A Lette

- Page 448 and 449:

Personality 411 LEARNING THEORY Aft

- Page 450 and 451:

Personality 413 Vicarious Reinforce

- Page 452 and 453:

Personality 415 is a function of S-

- Page 454 and 455:

Personality 417 Person-Centered App

- Page 456 and 457:

Personality 419 incongruence should

- Page 458 and 459:

Plate 15 Adjustment as a Continuous

- Page 460 and 461:

Personality 421 This approach somet

- Page 462:

Personality 423 Critical Terms Pers

- Page 466 and 467:

Adjustment and Maladjustment 427 PR

- Page 468 and 469:

Adjustment and Maladjustment 429 -

- Page 470 and 471:

Adjustment and Maladjustment 431 Av

- Page 472 and 473:

Adjustment and Maladjustment 433 Ag

- Page 474 and 475:

Adjustment and Maladjustment 435 Co

- Page 476 and 477:

Adjustment and Maladjustment 437 In

- Page 478 and 479:

Adjustment and Maladjustment 439 Fi

- Page 480 and 481:

Adjustment and Maladjustment 441 Ac

- Page 482 and 483:

Adjustment and Maladjustment 443 Fi

- Page 484 and 485:

Adjustment and Maladjustment 445 Ma

- Page 486 and 487:

Adjustment and Maladjustment 447 En

- Page 488 and 489:

Adjustment and Maladjustment 449 Fi

- Page 490 and 491:

Adjustment and Maladjustment 451 Si

- Page 492 and 493:

Adjustment and Maladjustment 453 13

- Page 494 and 495:

" *•. i" 'A *-t) V .c | to his д

- Page 496 and 497:

Therapy 457 But alcohol was only an

- Page 498 and 499:

Therapy 459 f-V '" ..;••*•:

- Page 500 and 501:

Therapy 461 merit, using somewhat d

- Page 502 and 503:

Therapy 463 T: "You did. You must h

- Page 504 and 505:

Therapy 465 A basic procedure in lo

- Page 506 and 507:

Therapy 467 Examination hierarchy 1

- Page 508 and 509:

Therapy 469 the food itself. Or may

- Page 510 and 511:

Therapy 471 Figure 17.12 Boxing and

- Page 512 and 513:

Therapy 473 Figure 17.14 JW's Mood

- Page 514 and 515:

Therapy 475 Influence of Drugs Drug

- Page 516 and 517:

Therapy 477 Problems in Measuring C

- Page 518 and 519:

Therapy 479 The extent to which any

- Page 520 and 521:

Therapy 481 2. In person-centered c

- Page 522 and 523:

Therapy 483 Suggested Readings Belk

- Page 527 and 528:

488 Psychology and Society These pe

- Page 529 and 530:

490 Psychology and Society Changing

- Page 531 and 532:

492 Psychology and Society Figure 1

- Page 533 and 534:

494 Psychology and Society In any r

- Page 535 and 536:

496 Psychology and Society INTERPER

- Page 537 and 538:

498 Psychology and Society Figure 1

- Page 539 and 540:

500 Psychology and Society 30 Figur

- Page 541 and 542:

502 Psychology and Society Figure 1

- Page 543 and 544:

504 Psychology and Society Figure 1

- Page 545 and 546:

506 Psychology and Society 'A situa

- Page 547 and 548:

508 Psychology and Society petition

- Page 549 and 550:

510 Psychology and Society terror i

- Page 551 and 552:

512 Psychology and Society Summary

- Page 555 and 556:

516 Psychology and Society Figure 1

- Page 557 and 558:

518 Psychology and Society This pro

- Page 559 and 560:

520 Psychology and Society Figure 1

- Page 561 and 562:

522 Psychology and Society Figure 1

- Page 563 and 564:

524 Psychology and Society METHODS

- Page 565 and 566:

526 Psychology and Society Figure 1

- Page 567 and 568:

528 Psychology and Society Row Figu

- Page 569 and 570:

530 Psychology and Society Study of

- Page 571 and 572:

532 Psychology and Society The quan

- Page 573:

534 Psychology and Society Cross Re

- Page 577 and 578:

538 Psychology and Society We begin

- Page 579 and 580:

540 Psychology and Society To find

- Page 581 and 582:

542 Psychology and Society Another

- Page 583 and 584:

544 Psychology and Society LAW AND

- Page 585 and 586:

546 Psychology and Society Figure 2

- Page 587 and 588:

648 Psychology and Society Research

- Page 589 and 590:

550 Psychology and Society Rank the

- Page 591 and 592:

552 Psychology and Society Figure 2

- Page 593 and 594:

554 Psychology and Society Architec

- Page 595 and 596:

556 Psychology and Society Figure 2

- Page 597 and 598:

558 Psychology and Society Televisi

- Page 599 and 600:

560 Psychology and Society Summary

- Page 602 and 603:

•*. -V . |Epiloguer* Psychology i

- Page 604:

Epilogue 565 Figure E.2 Research in

- Page 607 and 608:

568 Glossary affective state* A psy

- Page 609 and 610:

570 Glossary avoidance-avoidance co

- Page 611 and 612:

572 Glossary Clever Hans phenomenon

- Page 613 and 614:

574 Glossary consolidation theory A

- Page 615 and 616:

576 Glossary dependent variable An

- Page 617 and 618:

578 Glossary electroconvulsive ther

- Page 619 and 620:

580 Glossary fixed ratio reinforcem

- Page 621 and 622:

582 Glossary higher-order condition

- Page 623 and 624:

584 Glossary intensity The quantita

- Page 625 and 626:

586 Glossary Likert method An attit

- Page 627 and 628:

588 Glossary motor Pertaining to mu

- Page 629 and 630:

590 Glossary operations In the stru

- Page 631 and 632:

592 Glossary phobic disorder A stro

- Page 633 and 634:

594 Glossary psychoanalysis A syste

- Page 635 and 636:

596 Glossary relative movement in p

- Page 637 and 638:

598 Glossary self-reinforcement sch

- Page 639 and 640:

600 Glossary special classes An app

- Page 641 and 642:

602 Glossary telegraphic utterances

- Page 643 and 644:

604 Glossary variable A changeable

- Page 645 and 646:

606 References Bahrick, L. E., Walk

- Page 647 and 648:

608 References Cappon, D., & Banks,

- Page 649 and 650:

610 References Eysenck, H. J., & Ka

- Page 651 and 652:

612 References Guilford, J. P. (197

- Page 653 and 654:

614 References Jensen, A. R' (1969)

- Page 655 and 656:

616 References Limber, J. (1977). L

- Page 657 and 658:

618 References Moore, В. S. Underw

- Page 659 and 660:

620 References Roethlisberger, F. J

- Page 661 and 662:

622 References Skeels, H. M. (1973)

- Page 663 and 664:

624 References Van Gogh, V. (1888).

- Page 666 and 667:

life -"**. - _ T • is * * 4 = * i

- Page 668 and 669:

Credits 629 Chapter 3 Figure 3.4 Fr

- Page 670 and 671:

Name Index Aarons. L, 272 Abdel-Hal

- Page 672 and 673:

Index 633 Hirvonen. M. D., 295 Hitl

- Page 674:

Index 635 Sladen, W. J. L, 33 Slate

- Page 677 and 678:

638 Index California Personality In

- Page 679 and 680:

640 Index intelligence quotient (!Q

- Page 681 and 682:

642 Index reaction formation, 434 r