- Page 1 and 2:

BUILDING DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION HA

- Page 3 and 4:

CONTRIBUTORS David J. Akers Civil E

- Page 5 and 6:

ABOUT THE EDITORS Frederick S. Merr

- Page 7 and 8:

Contributors xxi Preface xxiii CONT

- Page 9 and 10:

GYPSUM PRODUCTS 4.26 Gypsumboard /

- Page 11 and 12:

CONTENTS ix Section 6 Soil Mechanic

- Page 13 and 14:

CONTENTS xi 8.22 Cellular Steel Flo

- Page 15 and 16:

CONTENTS xiii 9.80 Pile Foundations

- Page 17 and 18:

CONTENTS xv CERAMIC-TILE CONSTRUCTI

- Page 19 and 20:

13.14 Unit Heaters / 13.56 13.15 Ra

- Page 21 and 22:

CONTENTS xix Section 17 Constructio

- Page 23 and 24:

1.2 SECTION ONE Building design is

- Page 25 and 26:

1.4 SECTION ONE and performance of

- Page 27 and 28:

1.6 SECTION ONE building designers,

- Page 29 and 30:

1.8 SECTION ONE 1.5 ROLE OF THE CLI

- Page 31 and 32:

1.10 SECTION ONE other component is

- Page 33 and 34:

1.12 SECTION ONE FIGURE 1.3 Structu

- Page 35 and 36:

1.14 SECTION ONE 1.4g). Figure 1.4h

- Page 37 and 38:

1.16 SECTION ONE (a) FIGURE 1.6 Exa

- Page 39 and 40:

1.18 SECTION ONE transmit to suppor

- Page 41 and 42:

1.20 SECTION ONE Daylight is the so

- Page 43 and 44:

1.22 SECTION ONE vators may be prog

- Page 45 and 46:

1.24 SECTION ONE system may be more

- Page 47 and 48:

1.26 SECTION ONE after a specific n

- Page 49 and 50:

1.28 SECTION ONE all the necessary

- Page 51 and 52:

1.30 SECTION ONE 4. Employ techniqu

- Page 53 and 54:

1.32 SECTION ONE In listing objecti

- Page 55 and 56:

1.34 SECTION ONE Variables represen

- Page 57 and 58:

1.36 SECTION ONE Design of the foot

- Page 59 and 60:

1.38 SECTION ONE with noncombustibl

- Page 61 and 62:

1.40 SECTION ONE permits the buildi

- Page 63 and 64:

1.42 SECTION ONE Systems design sho

- Page 65 and 66:

2.2 SECTION TWO 2.1 PROFESSIONAL AN

- Page 67 and 68:

2.4 SECTION TWO quality systems, mo

- Page 69 and 70:

2.6 SECTION TWO neering firm. The p

- Page 71 and 72:

2.8 SECTION TWO For projects where

- Page 73 and 74:

2.10 SECTION TWO permits clients to

- Page 75 and 76:

2.12 SECTION TWO 2.9 ACCELERATED DE

- Page 77 and 78:

2.14 SECTION TWO the architect’s

- Page 79 and 80:

2.16 SECTION TWO centers, and indoo

- Page 81 and 82:

2.18 SECTION TWO 2.16 COST ESTIMATI

- Page 83 and 84:

2.20 SECTION TWO 9. Finishes 10. Sp

- Page 85 and 86:

2.22 SECTION TWO stitute format (Ar

- Page 87 and 88:

2.24 SECTION TWO 2.20 BIDDING AND C

- Page 89 and 90:

2.26 SECTION TWO 2.23 ROLE OF ARCHI

- Page 91 and 92:

2.28 SECTION TWO proposed by the co

- Page 93 and 94:

2.30 SECTION TWO client, building e

- Page 95 and 96:

2.32 SECTION TWO place. It is the p

- Page 97 and 98:

3.2 SECTION THREE tall and narrow,

- Page 99 and 100:

3.4 SECTION THREE it is known for a

- Page 101 and 102:

3.6 SECTION THREE ing damage by win

- Page 103 and 104:

3.8 SECTION THREE large that the st

- Page 105 and 106:

3.10 SECTION THREE forces. Generall

- Page 107 and 108:

3.12 SECTION THREE directions, both

- Page 109 and 110:

3.14 SECTION THREE mic loads, on th

- Page 111 and 112:

3.16 SECTION THREE be protected wit

- Page 113 and 114:

3.18 SECTION THREE The primary drai

- Page 115 and 116:

3.20 SECTION THREE should preferabl

- Page 117 and 118:

3.22 SECTION THREE where the walls

- Page 119 and 120:

3.24 SECTION THREE If the concrete

- Page 121 and 122:

3.26 SECTION THREE Factory-made por

- Page 123 and 124:

3.28 SECTION THREE and aqueous disp

- Page 125 and 126:

3.30 SECTION THREE community. In th

- Page 127 and 128:

3.32 SECTION THREE FIGURE 3.9 Time-

- Page 129 and 130:

3.34 SECTION THREE (‘‘Life Safe

- Page 131 and 132:

3.36 SECTION THREE For Class C fire

- Page 133 and 134:

3.38 SECTION THREE Hazard to person

- Page 135 and 136:

3.40 SECTION THREE Photoelectric De

- Page 137 and 138:

3.42 SECTION THREE High-Rise Buildi

- Page 139 and 140:

3.44 SECTION THREE Interior stairs

- Page 141 and 142:

3.46 SECTION THREE TABLE 3.6 Typica

- Page 143 and 144:

3.48 SECTION THREE necessary superv

- Page 145 and 146:

3.50 SECTION THREE The key element

- Page 147 and 148:

3.52 SECTION THREE 1. Detect a brea

- Page 149 and 150:

4.2 SECTION FOUR Limes, wherein the

- Page 151 and 152:

4.4 SECTION FOUR TABLE 4.1 Chemical

- Page 153 and 154:

4.6 SECTION FOUR TABLE 4.3 Relative

- Page 155 and 156:

4.8 SECTION FOUR Plasticity of mort

- Page 157 and 158:

4.10 SECTION FOUR Fly ashes are pro

- Page 159 and 160:

4.12 SECTION FOUR National Stone As

- Page 161 and 162:

4.14 SECTION FOUR 4.11.9 Volume Sta

- Page 163 and 164:

4.16 SECTION FOUR with less cement

- Page 165 and 166:

4.18 SECTION FOUR of color requires

- Page 167 and 168:

4.20 SECTION FOUR sometimes encount

- Page 169 and 170:

4.22 SECTION FOUR 4.17.1 Normal-Wei

- Page 171 and 172:

4.24 SECTION FOUR weights range fro

- Page 173 and 174:

4.26 SECTION FOUR TABLE 4.6 High-Pe

- Page 175 and 176:

4.28 SECTION FOUR of 4 � 8 � 16

- Page 177 and 178:

4.30 SECTION FOUR TABLE 4.8 Physica

- Page 179 and 180:

4.32 SECTION FOUR 4.22 CERAMIC TILE

- Page 181 and 182:

4.34 SECTION FOUR No. 305, Vol. 20,

- Page 183 and 184:

4.36 SECTION FOUR Gypsum Wallboard.

- Page 185 and 186:

4.38 SECTION FOUR two thicknesses

- Page 187 and 188:

4.40 SECTION FOUR Transparent Mirro

- Page 189 and 190:

TABLE 4.14 Strength of Some Commerc

- Page 191 and 192:

4.44 SECTION FOUR as longitudinal,

- Page 193 and 194:

4.46 SECTION FOUR it is usually at

- Page 195 and 196:

4.48 SECTION FOUR ified or of given

- Page 197 and 198:

4.50 SECTION FOUR pumped in under p

- Page 199 and 200:

4.52 SECTION FOUR both faces, excep

- Page 201 and 202:

TABLE 4.16 ASTM Requirements for St

- Page 203 and 204:

4.56 SECTION FOUR Above 2.0% carbon

- Page 205 and 206:

4.58 SECTION FOUR High-strength, lo

- Page 207 and 208:

4.60 SECTION FOUR element is strain

- Page 209 and 210:

4.62 SECTION FOUR is usually heated

- Page 211 and 212:

TABLE 4.19 Effects of Alloying Elem

- Page 213 and 214:

TABLE 4.19 Effects of Alloying Elem

- Page 215 and 216:

4.68 SECTION FOUR strength of 75 ks

- Page 217 and 218:

4.70 SECTION FOUR for preventing di

- Page 219 and 220:

4.72 SECTION FOUR Semikilled steel

- Page 221 and 222:

4.74 SECTION FOUR 4.49 CORROSION OF

- Page 223 and 224:

4.76 SECTION FOUR alloys to indicat

- Page 225 and 226:

4.78 SECTION FOUR TABLE 4.22 Finish

- Page 227 and 228:

4.80 SECTION FOUR other metals, the

- Page 229 and 230:

4.82 SECTION FOUR trical sockets, d

- Page 231 and 232:

4.84 SECTION FOUR with good corrosi

- Page 233 and 234:

4.86 SECTION FOUR in resisting oxid

- Page 235 and 236:

4.88 SECTION FOUR into desired shap

- Page 237 and 238:

4.90 SECTION FOUR other thermosetti

- Page 239 and 240:

4.92 SECTION FOUR Nylon. Molded nyl

- Page 241 and 242:

4.94 SECTION FOUR These materials m

- Page 243 and 244:

4.96 SECTION FOUR indoor and outdoo

- Page 245 and 246:

4.98 SECTION FOUR 4.81.1 Built-Up R

- Page 247 and 248:

4.100 SECTION FOUR other because of

- Page 249 and 250:

4.102 SECTION FOUR PAINTS AND OTHER

- Page 251 and 252:

4.104 SECTION FOUR Titanium dioxide

- Page 253 and 254:

SECTION FIVE STRUCTURAL THEORY Akba

- Page 255 and 256:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.3 Torsional loa

- Page 257 and 258:

TABLE 5.1 Minimum Design Dead Loads

- Page 259 and 260:

TABLE 5.2 Minimum Design Live Loads

- Page 261 and 262:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.9 L � 20R R

- Page 263 and 264:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.11 Wind pressur

- Page 265 and 266:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.13 In ASCE-7-95

- Page 267 and 268:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.15 loaded with

- Page 269 and 270:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.17 Building cod

- Page 271 and 272:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.19 Suppose, for

- Page 273 and 274:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.21 Since for th

- Page 275 and 276:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.23 Since AL is

- Page 277 and 278:

FIGURE 5.7 Normal and shear stresse

- Page 279 and 280:

FIGURE 5.9 Mohr’s circle for stre

- Page 281 and 282:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.29 Circular Sec

- Page 283 and 284:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.31 FIGURE 5.11

- Page 285 and 286:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.33 FIGURE 5.18

- Page 287 and 288:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.35 The bending

- Page 289 and 290:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.37 FIGURE 5.22

- Page 291 and 292:

FIGURE 5.25 Unit stresses on a beam

- Page 293 and 294:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.41 of Mohr’s

- Page 295 and 296:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.43 The tangenti

- Page 297 and 298:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.45 FIGURE 5.29

- Page 299 and 300:

FIGURE 5.32 Concentrated load at an

- Page 301 and 302:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.49 FIGURE 5.35

- Page 303 and 304:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.51 FIGURE 5.38

- Page 305 and 306:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.53 FIGURE 5.41

- Page 307 and 308:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.55 I�R yo �

- Page 309 and 310:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.57 where ƒr

- Page 311 and 312:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.59 This assumes

- Page 313 and 314:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.61 column curve

- Page 315 and 316:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.63 force beginn

- Page 317 and 318:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.65 FIGURE 5.47

- Page 319 and 320:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.67 On the other

- Page 321 and 322:

FIGURE 5.50 Statically indeterminat

- Page 323 and 324:

FIGURE 5.51 Dummy unit-load method

- Page 325 and 326:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.73 FIGURE 5.53

- Page 327 and 328:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.75 principle st

- Page 329 and 330:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.77 AX � B, wh

- Page 331 and 332:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.79 FIGURE 5.59

- Page 333 and 334:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.81 L �L �

- Page 335 and 336:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.83 3EI K � (5

- Page 337 and 338:

FIGURE 5.66 Moments for concentrate

- Page 339 and 340:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.87 FIGURE 5.71

- Page 341 and 342:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.89 � � 4EI

- Page 343 and 344:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.91 end moments

- Page 345 and 346:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.93 At A, for wh

- Page 347 and 348:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.95 the columns

- Page 349 and 350:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.97 5.11.10 Rapi

- Page 351 and 352:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.99 Similarly, a

- Page 353 and 354:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.101 ported beam

- Page 355 and 356:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.103 FIGURE 5.83

- Page 357 and 358:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.105 Wall A: 6.6

- Page 359 and 360:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.107 designed wi

- Page 361 and 362:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.109 1 � �

- Page 363 and 364:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.111 a thin plat

- Page 365 and 366:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.113 independent

- Page 367 and 368:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.115 k1 0 ... 0

- Page 369 and 370:

5.14.2 Two-Hinged Arches FIGURE 5.9

- Page 371 and 372:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.119 forces acti

- Page 373 and 374:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.121 FIGURE 5.97

- Page 375 and 376:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.123 � � 2 V

- Page 377 and 378:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.125 FIGURE 5.99

- Page 379 and 380:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.127 E 166.7h m

- Page 381 and 382:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.129 roof girder

- Page 383 and 384:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.131 H q o �1

- Page 385 and 386:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.133 wl o TL �

- Page 387 and 388:

5.16.2 Cable Systems STRUCTURAL THE

- Page 389 and 390:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.137 natural fre

- Page 391 and 392:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.139 FIGURE 5.10

- Page 393 and 394:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.141 methods tha

- Page 395 and 396:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.143 load that p

- Page 397 and 398:

� W 1 2 STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.145 k

- Page 399 and 400:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.147 mass has an

- Page 401 and 402:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.149 An approxim

- Page 403 and 404:

For smaller values of �, it is gi

- Page 405 and 406:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.153 k � sprin

- Page 407 and 408:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.155 FIGURE 5.11

- Page 409 and 410:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.157 New York; N

- Page 411 and 412:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.159 Eq. (5.289)

- Page 413 and 414:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.161 equivalent

- Page 415 and 416:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.163 R in Table

- Page 417 and 418:

TABLE 5.9 Design Coefficients and F

- Page 419 and 420:

TABLE 5.9 Design Coefficients and F

- Page 421 and 422:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.169 TABLE 5.10

- Page 423 and 424:

TABLE 5.13 Vertical Structural Irre

- Page 425 and 426:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.173 TABLE 5.15

- Page 427 and 428:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.175 • S a sha

- Page 429 and 430:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.177 where C T

- Page 431 and 432:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.179 • 1.0 for

- Page 433 and 434:

where r � max STRUCTURAL THEORY 5

- Page 435 and 436:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.183 0.3S DSI pW

- Page 437 and 438:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.185 TABLE 5.20

- Page 439 and 440:

STRUCTURAL THEORY 5.187 FIGURE 5.11

- Page 441 and 442:

SECTION SIX SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUN

- Page 443 and 444:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.3

- Page 445 and 446:

TABLE 6.2 Common Types of Foundatio

- Page 447 and 448:

TABLE 6.3 Boring, Core Drilling, Sa

- Page 449 and 450:

TABLE 6.3 Boring, Core Drilling, Sa

- Page 451 and 452:

TABLE 6.3 Boring, Core Drilling, Sa

- Page 453 and 454:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.13

- Page 455 and 456:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.15

- Page 457 and 458:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.17

- Page 459 and 460:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.19

- Page 461 and 462:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.21

- Page 463 and 464:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.23

- Page 465 and 466:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.25

- Page 467 and 468:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.27

- Page 469 and 470:

TABLE 6.7 Mass and Volume Relations

- Page 471 and 472:

TABLE 6.8 Unified Soil Classificati

- Page 473 and 474:

FIGURE 6.9 Plasticity chart. SOIL M

- Page 475 and 476:

Notes: 1. Classification Procedure:

- Page 477 and 478:

6.37 TABLE 6.10 Soil Classification

- Page 479 and 480:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.39

- Page 481 and 482:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.41

- Page 483 and 484:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.43

- Page 485 and 486:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.45

- Page 487 and 488:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.47

- Page 489 and 490:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.49

- Page 491 and 492:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.51

- Page 493 and 494:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.53

- Page 495 and 496:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.55

- Page 497 and 498:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.57

- Page 499 and 500:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.59

- Page 501 and 502:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.61

- Page 503 and 504:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.63

- Page 505 and 506:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.65

- Page 507 and 508:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.67

- Page 509 and 510:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.69

- Page 511 and 512:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.71

- Page 513 and 514:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.73

- Page 515 and 516:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.75

- Page 517 and 518:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.77

- Page 519 and 520:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.79

- Page 521 and 522:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.81

- Page 523 and 524:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.83

- Page 525 and 526:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.85

- Page 527 and 528:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.87

- Page 529 and 530:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.89

- Page 531 and 532:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.91

- Page 533 and 534:

TABLE 6.15 Typical Pile Characteris

- Page 535 and 536:

TABLE 6.15 Typical Pile Characteris

- Page 537 and 538:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.97

- Page 539 and 540:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.99

- Page 541 and 542:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.10

- Page 543 and 544:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.10

- Page 545 and 546:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.10

- Page 547 and 548:

TABLE 6.20 Characterics of Compacte

- Page 549 and 550:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.10

- Page 551 and 552:

TABLE 6.21 Site Improvement Methods

- Page 553 and 554:

TABLE 6.21 Site Improvement Methods

- Page 555 and 556:

6.11 GEOSYNTHETICS SOIL MECHANICS A

- Page 557 and 558:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.11

- Page 559 and 560:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.11

- Page 561 and 562:

SOIL MECHANICS AND FOUNDATIONS 6.12

- Page 563 and 564:

7.2 SECTION SEVEN by the fabricator

- Page 565 and 566:

7.4 SECTION SEVEN 7.2.1 Grades of S

- Page 567 and 568:

7.6 SECTION SEVEN recommended stand

- Page 569 and 570:

7.8 SECTION SEVEN 7.3 FASTENERS Two

- Page 571 and 572:

7.10 SECTION SEVEN TABLE 7.5 Washer

- Page 573 and 574:

7.12 SECTION SEVEN riveting gun, en

- Page 575 and 576:

7.14 SECTION SEVEN TABLE 7.7 Minimu

- Page 577 and 578:

7.16 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.5 Symbo

- Page 579 and 580:

7.18 SECTION SEVEN owner, design pr

- Page 581 and 582:

7.20 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.7 Wall-

- Page 583 and 584:

7.22 SECTION SEVEN than all forms o

- Page 585 and 586:

7.24 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.11 Type

- Page 587 and 588:

7.26 SECTION SEVEN to carry little

- Page 589 and 590:

7.28 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.14 Stee

- Page 591 and 592:

7.30 SECTION SEVEN Composite constr

- Page 593 and 594:

7.32 SECTION SEVEN Moment-Resisting

- Page 595 and 596:

7.34 SECTION SEVEN walls; neverthel

- Page 597 and 598:

7.36 SECTION SEVEN ities, size, spa

- Page 599 and 600:

7.38 SECTION SEVEN answer requires

- Page 601 and 602:

7.40 SECTION SEVEN Resistance to la

- Page 603 and 604:

7.42 SECTION SEVEN Temporary covera

- Page 605 and 606:

7.44 SECTION SEVEN filler blocks—

- Page 607 and 608:

7.46 SECTION SEVEN TABLE 7.9 Handbo

- Page 609 and 610:

7.48 SECTION SEVEN ing stress ƒ b

- Page 611 and 612:

7.50 SECTION SEVEN TABLE 7.11 Tensi

- Page 613 and 614:

7.52 SECTION SEVEN Constructions th

- Page 615 and 616:

FIGURE 7.29 Maximum width-thickness

- Page 617 and 618:

7.56 SECTION SEVEN unimportance of

- Page 619 and 620:

7.58 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.30 Requ

- Page 621 and 622:

7.60 SECTION SEVEN Compactness Requ

- Page 623 and 624:

7.62 SECTION SEVEN TABLE 7.14 Allow

- Page 625 and 626:

7.64 SECTION SEVEN TABLE 7.16 Limit

- Page 627 and 628:

7.66 SECTION SEVEN 2 Mcr � C b (

- Page 629 and 630: 7.68 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.33 Plat

- Page 631 and 632: 7.70 SECTION SEVEN are welded perpe

- Page 633 and 634: 7.72 SECTION SEVEN 2 1 � Cva (a/h

- Page 635 and 636: 7.74 SECTION SEVEN of lateral-torsi

- Page 637 and 638: 7.76 SECTION SEVEN 7.22 WEB OR FLAN

- Page 639 and 640: 7.78 SECTION SEVEN 3 4100 t �Fyc

- Page 641 and 642: 7.80 SECTION SEVEN For expansion ro

- Page 643 and 644: 7.82 SECTION SEVEN where M nt � r

- Page 645 and 646: 7.84 SECTION SEVEN Connector Detail

- Page 647 and 648: 7.86 SECTION SEVEN prevent overstre

- Page 649 and 650: 7.88 SECTION SEVEN H � length of

- Page 651 and 652: 7.90 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.39 Stee

- Page 653 and 654: 7.92 SECTION SEVEN 7.30.1 ASD for B

- Page 655 and 656: 7.94 SECTION SEVEN TABLE 7.26 Desig

- Page 657 and 658: 7.96 SECTION SEVEN be subject to fa

- Page 659 and 660: 7.98 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.41 Ecce

- Page 661 and 662: 7.100 SECTION SEVEN axis equals the

- Page 663 and 664: 7.102 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.44 Typ

- Page 665 and 666: 7.104 SECTION SEVEN not a factor. S

- Page 667 and 668: 7.106 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.48 Wel

- Page 669 and 670: 7.108 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.50 End

- Page 671 and 672: 7.110 SECTION SEVEN and usually ind

- Page 673 and 674: 7.112 SECTION SEVEN or welded const

- Page 675 and 676: 7.114 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.55 Wel

- Page 677 and 678: 7.116 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.57 Wel

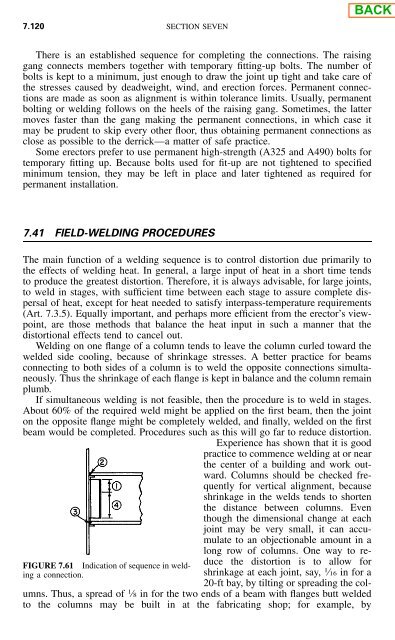

- Page 679: 7.118 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.58 Ere

- Page 683 and 684: 7.122 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.62 Per

- Page 685 and 686: 7.124 SECTION SEVEN The whole opera

- Page 687 and 688: 7.126 SECTION SEVEN common service

- Page 689 and 690: 7.128 SECTION SEVEN 1. Steel that i

- Page 691 and 692: 7.130 SECTION SEVEN that the steel

- Page 693 and 694: 7.132 SECTION SEVEN FIGURE 7.65 Fir

- Page 695 and 696: 7.134 SECTION SEVEN American Instit

- Page 697 and 698: 8.2 SECTION EIGHT Cold-formed shape

- Page 699 and 700: TABLE 8-2 Principal Mechanical Prop

- Page 701 and 702: TABLE 8-2 Principal Mechanical Prop

- Page 703 and 704: 8.8 SECTION EIGHT TABLE 8.3 Gages,

- Page 705 and 706: 8.10 SECTION EIGHT FIGURE 8.2 Misce

- Page 707 and 708: TABLE 8.4 Properties of Area and Li

- Page 709 and 710: 8.14 SECTION EIGHT The Committee on

- Page 711 and 712: 8.16 SECTION EIGHT In 1932, von Kar

- Page 713 and 714: 8.18 FIGURE 8.6 Schematic diagrams

- Page 715 and 716: 8.20 SECTION EIGHT Webs Subjected t

- Page 717 and 718: 8.22 SECTION EIGHT 8.9 MAXIMUM FLAT

- Page 719 and 720: 8.24 SECTION EIGHT where P n � ul

- Page 721 and 722: 8.26 SECTION EIGHT weld quality. Me

- Page 723 and 724: 8.28 SECTION EIGHT other sheets of

- Page 725 and 726: 8.30 SECTION EIGHT may be used to c

- Page 727 and 728: 8.32 SECTION EIGHT TABLE 8.5 Design

- Page 729 and 730: 8.34 SECTION EIGHT TABLE 8.7 ASTM B

- Page 731 and 732:

8.36 SECTION EIGHT TABLE 8.9 Nomina

- Page 733 and 734:

8.38 SECTION EIGHT TABLE 8.11 Nomin

- Page 735 and 736:

8.40 SECTION EIGHT 8.19 SELF-TAPPIN

- Page 737 and 738:

8.42 SECTION EIGHT FIGURE 8.13 Roof

- Page 739 and 740:

8.44 TABLE 8.13 Allowable Total (De

- Page 741 and 742:

8.46 SECTION EIGHT Maximum Deflecti

- Page 743 and 744:

8.48 SECTION EIGHT TABLE 8.14 Fire

- Page 745 and 746:

8.50 SECTION EIGHT service outlets

- Page 747 and 748:

8.52 SECTION EIGHT K � pitch-dept

- Page 749 and 750:

8.54 SECTION EIGHT TABLE 8.15 Physi

- Page 751 and 752:

8.56 SECTION EIGHT Many preengineer

- Page 753 and 754:

8.58 SECTION EIGHT Construction (AI

- Page 755 and 756:

SECTION NINE CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION

- Page 757 and 758:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.3 FIGURE 9.

- Page 759 and 760:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.5 the owner

- Page 761 and 762:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.7 proportio

- Page 763 and 764:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.9 In additi

- Page 765 and 766:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.11 entraini

- Page 767 and 768:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.13 greatly

- Page 769 and 770:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.15 TABLE 9.

- Page 771 and 772:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.17 Other AC

- Page 773 and 774:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.19 Conventi

- Page 775 and 776:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.21 For exam

- Page 777 and 778:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.23 formwork

- Page 779 and 780:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.25 dropped

- Page 781 and 782:

TABLE 9.4 ASTM Standard Rebars Bar

- Page 783 and 784:

TABLE 9.6 Standard Wire Sizes for R

- Page 785 and 786:

TABLE 9.7 Standard Hooks* (Continue

- Page 787 and 788:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.33 as well

- Page 789 and 790:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.35 ditions

- Page 791 and 792:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.37 For conc

- Page 793 and 794:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.39 In pract

- Page 795 and 796:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.41 The engi

- Page 797 and 798:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.43 FIGURE 9

- Page 799 and 800:

9.43 SPECIAL ANALYSES CONCRETE CONS

- Page 801 and 802:

9.44.2 Load Factors CONCRETE CONSTR

- Page 803 and 804:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.49 section;

- Page 805 and 806:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.51 that A s

- Page 807 and 808:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.53 FIGURE 9

- Page 809 and 810:

9.48 TORSION IN REINFORCED CONCRETE

- Page 811 and 812:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.57 Where to

- Page 813 and 814:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.59 9.49.2 D

- Page 815 and 816:

where � � 0.8 for bar sizes #3-

- Page 817 and 818:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.63 TABLE 9.

- Page 819 and 820:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.65 exceeds

- Page 821 and 822:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.67 FIGURE 9

- Page 823 and 824:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.69 length r

- Page 825 and 826:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.71 yield st

- Page 827 and 828:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.73 where Mc

- Page 829 and 830:

ONE-WAY REINFORCED-CONCRETE SLABS C

- Page 831 and 832:

9.53 EMBEDDED PIPES IN ONE-WAY SLAB

- Page 833 and 834:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.79 One-way

- Page 835 and 836:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.81 Minimum

- Page 837 and 838:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.83 FIGURE 9

- Page 839 and 840:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.85 Step 2.

- Page 841 and 842:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.87 where

- Page 843 and 844:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.89 FIGURE 9

- Page 845 and 846:

TABLE 9.21 Commonly Used Sizes of T

- Page 847 and 848:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.93 and the

- Page 849 and 850:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.95 FIGURE 9

- Page 851 and 852:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.97 Need for

- Page 853 and 854:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.99 tored sh

- Page 855 and 856:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.101 TABLE 9

- Page 857 and 858:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.103 If slen

- Page 859 and 860:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.105 FIGURE

- Page 861 and 862:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.107 FIGURE

- Page 863 and 864:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.109 2P u qs

- Page 865 and 866:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.111 dicated

- Page 867 and 868:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.113 FIGURE

- Page 869 and 870:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.115 loads u

- Page 871 and 872:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.117 C r �

- Page 873 and 874:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.119 TABLE 9

- Page 875 and 876:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.121 checked

- Page 877 and 878:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.123 2. For

- Page 879 and 880:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.125 FIGURE

- Page 881 and 882:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.127 TABLE 9

- Page 883 and 884:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.129 greates

- Page 885 and 886:

FIGURE 9.55 Reinforcement for deep

- Page 887 and 888:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.133 � �

- Page 889 and 890:

FIGURE 9.58 Continuous cylindrical

- Page 891 and 892:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.137 require

- Page 893 and 894:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.139 crete s

- Page 895 and 896:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.141 TABLE 9

- Page 897 and 898:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.143 Forms r

- Page 899 and 900:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.145 an uncr

- Page 901 and 902:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.147 may be

- Page 903 and 904:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.149 sions a

- Page 905 and 906:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.151 Nonpres

- Page 907 and 908:

CONCRETE CONSTRUCTION 9.153 If the

- Page 909 and 910:

9.111 APPLICATION AND MEASUREMENT O

- Page 911 and 912:

10.2 TABLE 10.1 Shrinkage Values of

- Page 913 and 914:

10.4 SECTION TEN this structure, st

- Page 915 and 916:

10.6 SECTION TEN Use standard detai

- Page 917 and 918:

TABLE 10.4 Weights and Specific Gra

- Page 919 and 920:

10.10 SECTION TEN 10.3 DESIGN VALUE

- Page 921 and 922:

10.12 SECTION TEN Cr � repetitive

- Page 923 and 924:

10.14 SECTION TEN TABLE 10.6 Wet Se

- Page 925 and 926:

10.16 SECTION TEN 10.5.7 Flat-Use F

- Page 927 and 928:

10.18 SECTION TEN of loading. These

- Page 929 and 930:

10.20 SECTION TEN good joint detail

- Page 931 and 932:

10.22 SECTION TEN direction, deflec

- Page 933 and 934:

10.24 SECTION TEN Deflection of woo

- Page 935 and 936:

10.26 SECTION TEN multiplied by app

- Page 937 and 938:

10.28 SECTION TEN 10.8 WOOD COMPRES

- Page 939 and 940:

10.30 SECTION TEN smaller the slip

- Page 941 and 942:

10.32 SECTION TEN 2 FbE � KbEE�

- Page 943 and 944:

10.34 SECTION TEN A structural pane

- Page 945 and 946:

10.36 SECTION TEN panels, primarily

- Page 947 and 948:

10.38 SECTION TEN 10.12.5 Availabil

- Page 949 and 950:

10.40 SECTION TEN FIGURE 10.7 Subfl

- Page 951 and 952:

Panel siding Lap siding 10.42 TABLE

- Page 953 and 954:

10.44 SECTION TEN Building paper is

- Page 955 and 956:

10.46 TABLE 10.23 Maximum Shear, lb

- Page 957 and 958:

10.48 SECTION TEN FIGURE 10.10 Foun

- Page 959 and 960:

10.50 SECTION TEN TABLE 10.26 Minim

- Page 961 and 962:

10.52 TABLE 10.27 Maximum Shear, lb

- Page 963 and 964:

10.54 SECTION TEN 10.14.2 Wet-Servi

- Page 965 and 966:

10.56 SECTION TEN TABLE 10.30 Tempe

- Page 967 and 968:

10.58 SECTION TEN TABLE 10.32 Penet

- Page 969 and 970:

10.60 SECTION TEN FIGURE 10.12 Bolt

- Page 971 and 972:

10.62 SECTION TEN plates, embedded

- Page 973 and 974:

10.64 TABLE 10.37 Minimum Edge and

- Page 975 and 976:

10.66 SECTION TEN steel nails and s

- Page 977 and 978:

10.68 SECTION TEN FIGURE 10.15 Typi

- Page 979 and 980:

10.70 SECTION TEN Chord splices are

- Page 981 and 982:

10.72 SECTION TEN Horizontal framin

- Page 983 and 984:

10.74 SECTION TEN FIGURE 10.20 Crow

- Page 985 and 986:

10.76 SECTION TEN FIGURE 10.22 Typi

- Page 987 and 988:

10.78 SECTION TEN FIGURE 10.23 Plat

- Page 989 and 990:

10.80 SECTION TEN 10.26 PERMANENT W

- Page 991 and 992:

10.82 SECTION TEN Bearing values un

- Page 993 and 994:

10.84 SECTION TEN evacuation, fire

- Page 995 and 996:

10.86 SECTION TEN End Cuts. Unless

- Page 997 and 998:

10.88 SECTION TEN dapping, or drill

- Page 999 and 1000:

10.90 SECTION TEN Narrow boards may

- Page 1001 and 1002:

10.92 SECTION TEN wood species do n

- Page 1003 and 1004:

10.94 SECTION TEN In addition to ex

- Page 1005 and 1006:

11.2 SECTION ELEVEN MASONRY WALLS M

- Page 1007 and 1008:

11.4 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.1 Bri

- Page 1009 and 1010:

11.6 SECTION ELEVEN Design of load-

- Page 1011 and 1012:

11.8 SECTION ELEVEN For concrete bl

- Page 1013 and 1014:

11.10 SECTION ELEVEN Materials to b

- Page 1015 and 1016:

11.12 SECTION ELEVEN the ends of ti

- Page 1017 and 1018:

11.14 SECTION ELEVEN to distribute

- Page 1019 and 1020:

11.16 SECTION ELEVEN 11.4 LATERAL S

- Page 1021 and 1022:

11.18 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.9 An

- Page 1023 and 1024:

11.20 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.10 C

- Page 1025 and 1026:

11.22 SECTION ELEVEN saturation. Wh

- Page 1027 and 1028:

11.24 SECTION ELEVEN with metal anc

- Page 1029 and 1030:

11.26 SECTION ELEVEN TABLE 11.4 All

- Page 1031 and 1032:

11.28 SECTION ELEVEN TABLE 11.6 All

- Page 1033 and 1034:

11.30 SECTION ELEVEN Slenderness Co

- Page 1035 and 1036:

11.32 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.12 S

- Page 1037 and 1038:

11.34 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.15 (

- Page 1039 and 1040:

11.36 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.17 E

- Page 1041 and 1042:

11.38 SECTION ELEVEN 11.17 WOOD FAC

- Page 1043 and 1044:

11.40 SECTION ELEVEN be applied wit

- Page 1045 and 1046:

11.42 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.19 M

- Page 1047 and 1048:

11.44 SECTION ELEVEN in the followi

- Page 1049 and 1050:

11.46 SECTION ELEVEN Batten. A pred

- Page 1051 and 1052:

11.48 SECTION ELEVEN Corner Bead. A

- Page 1053 and 1054:

11.50 SECTION ELEVEN Gypsumboard. A

- Page 1055 and 1056:

11.52 SECTION ELEVEN Ship Lap. An o

- Page 1057 and 1058:

11.54 SECTION ELEVEN 11.25.2 Plaste

- Page 1059 and 1060:

11.56 SECTION ELEVEN Except at inte

- Page 1061 and 1062:

11.58 SECTION ELEVEN loops of 18-ga

- Page 1063 and 1064:

11.60 SECTION ELEVEN Veneer plaster

- Page 1065 and 1066:

11.62 SECTION ELEVEN Veneer plaster

- Page 1067 and 1068:

11.64 SECTION ELEVEN Furring. Suppl

- Page 1069 and 1070:

11.66 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.25 W

- Page 1071 and 1072:

11.68 SECTION ELEVEN TABLE 11.11 Ma

- Page 1073 and 1074:

11.70 SECTION ELEVEN The first step

- Page 1075 and 1076:

11.72 SECTION ELEVEN The joint shou

- Page 1077 and 1078:

11.74 SECTION ELEVEN masonry, or po

- Page 1079 and 1080:

11.76 SECTION ELEVEN may be 3 ⁄4

- Page 1081 and 1082:

11.78 SECTION ELEVEN 11.31 OTHER TY

- Page 1083 and 1084:

11.80 SECTION ELEVEN is practically

- Page 1085 and 1086:

11.82 SECTION ELEVEN Wood subfloors

- Page 1087 and 1088:

11.84 SECTION ELEVEN Because of the

- Page 1089 and 1090:

11.86 SECTION ELEVEN clay tiles and

- Page 1091 and 1092:

11.88 SECTION ELEVEN Check Rails. M

- Page 1093 and 1094:

11.90 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.31 D

- Page 1095 and 1096:

11.92 SECTION ELEVEN Hot-Dipped Gal

- Page 1097 and 1098:

11.94 SECTION ELEVEN TABLE 11.14 Re

- Page 1099 and 1100:

11.96 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.34 D

- Page 1101 and 1102:

11.98 SECTION ELEVEN commodation of

- Page 1103 and 1104:

11.100 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.37

- Page 1105 and 1106:

11.102 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.43

- Page 1107 and 1108:

11.104 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.47

- Page 1109 and 1110:

11.106 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.55

- Page 1111 and 1112:

11.108 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.59

- Page 1113 and 1114:

11.110 SECTION ELEVEN Hinge jambs o

- Page 1115 and 1116:

11.112 SECTION ELEVEN Control of Ai

- Page 1117 and 1118:

11.114 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.61

- Page 1119 and 1120:

11.116 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.63

- Page 1121 and 1122:

11.118 SECTION ELEVEN one rising up

- Page 1123 and 1124:

11.120 SECTION ELEVEN 11.56 REVOLVI

- Page 1125 and 1126:

11.122 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.68

- Page 1127 and 1128:

11.124 SECTION ELEVEN doors and win

- Page 1129 and 1130:

11.126 SECTION ELEVEN ANSI A156.4.

- Page 1131 and 1132:

11.128 SECTION ELEVEN 2. Nonrising

- Page 1133 and 1134:

11.130 SECTION ELEVEN it is importa

- Page 1135 and 1136:

11.132 SECTION ELEVEN When floor-ty

- Page 1137 and 1138:

11.134 SECTION ELEVEN that may be m

- Page 1139 and 1140:

11.136 SECTION ELEVEN The security

- Page 1141 and 1142:

11.138 SECTION ELEVEN Metal anchors

- Page 1143 and 1144:

11.140 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.84

- Page 1145 and 1146:

11.142 SECTION ELEVEN of the stud w

- Page 1147 and 1148:

11.144 SECTION ELEVEN 11.74 BOLTS A

- Page 1149 and 1150:

11.146 SECTION ELEVEN Velocity. Spe

- Page 1151 and 1152:

11.148 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.91

- Page 1153 and 1154:

11.150 SECTION ELEVEN p SPL � 20

- Page 1155 and 1156:

11.152 SECTION ELEVEN FIGURE 11.92

- Page 1157 and 1158:

11.154 SECTION ELEVEN Structural fl

- Page 1159 and 1160:

11.156 SECTION ELEVEN 11.79.4 Dampi

- Page 1161 and 1162:

11.158 SECTION ELEVEN binders or th

- Page 1163 and 1164:

11.160 SECTION ELEVEN Reverberation

- Page 1165 and 1166:

11.162 SECTION ELEVEN acoustical ce

- Page 1167 and 1168:

11.164 SECTION ELEVEN As might be e

- Page 1169 and 1170:

11.166 SECTION ELEVEN Acoustical Ab

- Page 1171 and 1172:

11.168 SECTION ELEVEN TABLE 11.35 T

- Page 1173 and 1174:

SECTION TWELVE ROOF SYSTEMS Dave Fl

- Page 1175 and 1176:

ROOF SYSTEMS 12.3 vapor in the inte

- Page 1177 and 1178:

ROOF SYSTEMS 12.5 it is the only ty

- Page 1179 and 1180:

ROOF SYSTEMS 12.7 Bitumen may be as

- Page 1181 and 1182:

ROOF SYSTEMS 12.9 FIGURE 12.4 Torch

- Page 1183 and 1184:

FIGURE 12.5 (Continued ) ROOF SYSTE

- Page 1185 and 1186:

FIGURE 12.7 Three-tab asphalt-shing

- Page 1187 and 1188:

ROOF SYSTEMS 12.15 Metal roof panel

- Page 1189 and 1190:

ROOF SYSTEMS 12.17 FIGURE 12.11 Woo

- Page 1191 and 1192:

ROOF SYSTEMS 12.19 a system that is

- Page 1193 and 1194:

12.14 EFFECTS OF WIND ON ROOFS ROOF

- Page 1195 and 1196:

ROOF SYSTEMS 12.23 inspections and

- Page 1197 and 1198:

American Society of Heating, Refrig

- Page 1199 and 1200:

Roof Consultants Institute (RCI) 74

- Page 1201 and 1202:

SECTION THIRTEEN HEATING, VENTILATI

- Page 1203 and 1204:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1205 and 1206:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1207 and 1208:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1209 and 1210:

13.2.3 Sensible Heat HEATING, VENTI

- Page 1211 and 1212:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1213 and 1214:

13.2.7 Enthalpy HEATING, VENTILATIO

- Page 1215 and 1216:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1217 and 1218:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1219 and 1220:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1221 and 1222:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1223 and 1224:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1225 and 1226:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1227 and 1228:

13.4 VENTILATION HEATING, VENTILATI

- Page 1229 and 1230:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1231 and 1232:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1233 and 1234:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1235 and 1236:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1237 and 1238:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1239 and 1240:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1241 and 1242:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1243 and 1244:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1245 and 1246:

13.11 WARM-AIR HEATING HEATING, VEN

- Page 1247 and 1248:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1249 and 1250:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1251 and 1252:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1253 and 1254:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1255 and 1256:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1257 and 1258:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1259 and 1260:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1261 and 1262:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1263 and 1264:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1265 and 1266:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1267 and 1268:

TABLE 13.15b First-Floor Office Loa

- Page 1269 and 1270:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1271 and 1272:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1273 and 1274:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1275 and 1276:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1277 and 1278:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1279 and 1280:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1281 and 1282:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1283 and 1284:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1285 and 1286:

13.32 AIR-WATER SYSTEMS HEATING, VE

- Page 1287 and 1288:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1289 and 1290:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1291 and 1292:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1293 and 1294:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1295 and 1296:

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDI

- Page 1297 and 1298:

14.2 SECTION FOURTEEN Code,’’ A

- Page 1299 and 1300:

14.4 SECTION FOURTEEN Publishing Co

- Page 1301 and 1302:

14.6 SECTION FOURTEEN detergents ar

- Page 1303 and 1304:

14.8 SECTION FOURTEEN 14.6.1 Temper

- Page 1305 and 1306:

14.10 SECTION FOURTEEN FIGURE 14.2

- Page 1307 and 1308:

14.12 SECTION FOURTEEN 14.6.7 Valve

- Page 1309 and 1310:

TABLE 14.2 Minimum Plumbing Fixture

- Page 1311 and 1312:

TABLE 14.2 Minimum Plumbing Fixture

- Page 1313 and 1314:

14.18 SECTION FOURTEEN of people ma

- Page 1315 and 1316:

14.20 SECTION FOURTEEN TABLE 14.3 M

- Page 1317 and 1318:

TABLE 14.4 Fixture Units and Trap a

- Page 1319 and 1320:

14.24 SECTION FOURTEEN FIGURE 14.4

- Page 1321 and 1322:

14.26 SECTION FOURTEEN FIGURE 14.6

- Page 1323 and 1324:

TABLE 14.5 Allowances for Friction

- Page 1325 and 1326:

14.30 SECTION FOURTEEN 2. Indirect

- Page 1327 and 1328:

TABLE 14.6 Hot-Water Demand per Fix

- Page 1329 and 1330:

14.34 SECTION FOURTEEN Storm water

- Page 1331 and 1332:

14.36 SECTION FOURTEEN Size and slo

- Page 1333 and 1334:

14.38 SECTION FOURTEEN hub; threade

- Page 1335 and 1336:

14.40 SECTION FOURTEEN to the build

- Page 1337 and 1338:

14.42 SECTION FOURTEEN TABLE 14.9 S

- Page 1339 and 1340:

TABLE 14.12 Size and Length of Vent

- Page 1341 and 1342:

14.46 SECTION FOURTEEN To ensure th

- Page 1343 and 1344:

14.48 SECTION FOURTEEN FIGURE 14.12

- Page 1345 and 1346:

14.50 SECTION FOURTEEN Besides muni

- Page 1347 and 1348:

14.52 SECTION FOURTEEN Polyethylene

- Page 1349 and 1350:

14.54 SECTION FOURTEEN FIGURE 14.14

- Page 1351 and 1352:

14.56 SECTION FOURTEEN FIGURE 14.16

- Page 1353 and 1354:

14.58 SECTION FOURTEEN The indicati

- Page 1355 and 1356:

14.60 SECTION FOURTEEN 14.29.2 Spri

- Page 1357 and 1358:

14.62 SECTION FOURTEEN FIGURE 14.21

- Page 1359 and 1360:

14.64 SECTION FOURTEEN limiting dev

- Page 1361 and 1362:

SECTION FIFTEEN ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS

- Page 1363 and 1364:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.3 Resistance

- Page 1365 and 1366:

15.3 ALTERNATING-CURRENT SYSTEMS EL

- Page 1367 and 1368:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.7 The magneti

- Page 1369 and 1370:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.9 E � IZ co

- Page 1371 and 1372:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.11 FIGURE 15.

- Page 1373 and 1374:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.13 keeping th

- Page 1375 and 1376:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.15 erator. Op

- Page 1377 and 1378:

15.6.3 Types of Insulated Conductor

- Page 1379 and 1380:

FIGURE 15.6 Cellular steel decking

- Page 1381 and 1382:

15.21 FIGURE 15.7 Space beneath a r

- Page 1383 and 1384:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.23 All the se

- Page 1385 and 1386:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.25 clearly ma

- Page 1387 and 1388:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.27 customer u

- Page 1389 and 1390:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.29 control th

- Page 1391 and 1392:

TABLE 15.1 Electrical Symbols* (Con

- Page 1393 and 1394:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.33 CADD can m

- Page 1395 and 1396:

R � resistance, �/mil-ft c.m.

- Page 1397 and 1398:

TABLE 15.2 Protection of Single-Pha

- Page 1399 and 1400:

15.39 Horsepower TABLE 15.3 Protect

- Page 1401 and 1402:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.41 starting c

- Page 1403 and 1404:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.43 FIGURE 15.

- Page 1405 and 1406:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.45 2 Three 40

- Page 1407 and 1408:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.47 case, the

- Page 1409 and 1410:

15.10.5 Equivalent Spherical Illumi

- Page 1411 and 1412:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.51 See also A

- Page 1413 and 1414:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.53 Increase i

- Page 1415 and 1416:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.55 restaurant

- Page 1417 and 1418:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.57 TABLE 15.7

- Page 1419 and 1420:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.59 the result

- Page 1421 and 1422:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.61 acteristic

- Page 1423 and 1424:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.63 For contro

- Page 1425 and 1426:

15.65 TABLE 15.9 Comparison of Lamp

- Page 1427 and 1428:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.67 FIGURE 15.

- Page 1429 and 1430:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.69 Some lumin

- Page 1431 and 1432:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.71 To adjust

- Page 1433 and 1434:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.73 Similar co

- Page 1435 and 1436:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.75 exchange (

- Page 1437 and 1438:

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS 15.77 protection

- Page 1439 and 1440:

SECTION SIXTEEN VERTICAL CIRCULATIO

- Page 1441 and 1442:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.3 ft 2 . Ra

- Page 1443 and 1444:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.5 Facilitie

- Page 1445 and 1446:

16.3.3 Design Loads for Stairs VERT

- Page 1447 and 1448:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.9 Stairs ou

- Page 1449 and 1450:

FIGURE 16.5 Reinforced concrete sta

- Page 1451 and 1452:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.13 FIGURE 1

- Page 1453 and 1454:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.15 most att

- Page 1455 and 1456:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.17 FIGURE 1

- Page 1457 and 1458:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.19 FIGURE 1

- Page 1459 and 1460:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.21 Hoistway

- Page 1461 and 1462:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.23 enclosur

- Page 1463 and 1464:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.25 horizont

- Page 1465 and 1466:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.27 car is r

- Page 1467 and 1468:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.29 and lowe

- Page 1469 and 1470:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.31 car-spee

- Page 1471 and 1472:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.33 Also, th

- Page 1473 and 1474:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.35 An autom

- Page 1475 and 1476:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.37 For long

- Page 1477 and 1478:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.39 Another

- Page 1479 and 1480:

16.11.5 Professional-Building Eleva

- Page 1481 and 1482:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.43 FIGURE 1

- Page 1483 and 1484:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.45 horizont

- Page 1485 and 1486:

VERTICAL CIRCULATION 16.47 limited

- Page 1487 and 1488:

17.2 SECTION SEVENTEEN to be a good

- Page 1489 and 1490:

17.4 SECTION SEVENTEEN the contract

- Page 1491 and 1492:

17.6 SECTION SEVENTEEN 17.3 CONTRAC

- Page 1493 and 1494:

17.8 SECTION SEVENTEEN Private Cont

- Page 1495 and 1496:

17.10 SECTION SEVENTEEN FIGURE 17.2

- Page 1497 and 1498:

17.12 SECTION SEVENTEEN intend to a

- Page 1499 and 1500:

17.14 SECTION SEVENTEEN purposes. I

- Page 1501 and 1502:

17.16 SECTION SEVENTEEN 4. The CM a

- Page 1503 and 1504:

17.18 SECTION SEVENTEEN FIGURE 17.5

- Page 1505 and 1506:

17.20 SECTION SEVENTEEN FIGURE 17.6

- Page 1507 and 1508:

17.22 SECTION SEVENTEEN FIGURE 17.8

- Page 1509 and 1510:

17.24 SECTION SEVENTEEN Purchasing/

- Page 1511 and 1512:

17.26 SECTION SEVENTEEN FIGURE 17.1

- Page 1513 and 1514:

17.28 SECTION SEVENTEEN serving dec

- Page 1515 and 1516:

17.30 SECTION SEVENTEEN FIGURE 17.1

- Page 1517 and 1518:

17.32 SECTION SEVENTEEN FIGURE 17.1

- Page 1519 and 1520:

17.34 SECTION SEVENTEEN pass contin

- Page 1521 and 1522:

17.36 SECTION SEVENTEEN This may ne

- Page 1523 and 1524:

17.38 SECTION SEVENTEEN When work i

- Page 1525 and 1526:

17.40 SECTION SEVENTEEN work or to

- Page 1527 and 1528:

17.42 SECTION SEVENTEEN Mediation.

- Page 1529 and 1530:

17.44 SECTION SEVENTEEN TABLE 17.1

- Page 1531 and 1532:

17.46 SECTION SEVENTEEN TABLE 17.1

- Page 1533 and 1534:

17.48 SECTION SEVENTEEN 17.15.3 Mot

- Page 1535 and 1536:

17.50 SECTION SEVENTEEN independent

- Page 1537 and 1538:

17.52 SECTION SEVENTEEN merchandise

- Page 1539 and 1540:

17.54 SECTION SEVENTEEN 1. A comple

- Page 1541 and 1542:

17.56 SECTION SEVENTEEN retainage t

- Page 1543 and 1544:

17.58 SECTION SEVENTEEN FIGURE 17.2

- Page 1545 and 1546:

17.60 FIGURE 17.23 Monthly cost rep

- Page 1547 and 1548:

17.62 SECTION SEVENTEEN this method

- Page 1549 and 1550:

17.64 SECTION SEVENTEEN salaried li

- Page 1551 and 1552:

17.66 SECTION SEVENTEEN heat. Stand

- Page 1553 and 1554:

17.68 SECTION SEVENTEEN or three-sh

- Page 1555 and 1556:

17.70 SECTION SEVENTEEN The lessons

- Page 1557 and 1558:

18.2 SECTION EIGHTEEN the local uti

- Page 1559 and 1560:

18.4 SECTION EIGHTEEN nized steel (

- Page 1561 and 1562:

18.6 SECTION EIGHTEEN building cons

- Page 1563 and 1564:

18.8 SECTION EIGHTEEN tenant’s re

- Page 1565 and 1566:

18.10 SECTION EIGHTEEN 18.3 COMMUNI

- Page 1567 and 1568:

18.12 SECTION EIGHTEEN FIGURE 18.4

- Page 1569 and 1570:

18.14 SECTION EIGHTEEN FIGURE 18.7

- Page 1571 and 1572:

18.16 SECTION EIGHTEEN FIGURE 18.10

- Page 1573 and 1574:

18.18 SECTION EIGHTEEN FIGURE 18.14

- Page 1575 and 1576:

18.20 SECTION EIGHTEEN FIGURE 18.17

- Page 1577 and 1578:

18.22 SECTION EIGHTEEN FIGURE 18.21

- Page 1579 and 1580:

18.24 SECTION EIGHTEEN a 120/240 V,

- Page 1581 and 1582:

18.26 SECTION EIGHTEEN 18.9 LINKS A

- Page 1583 and 1584:

19.2 SECTION NINETEEN the course of

- Page 1585 and 1586:

19.4 SECTION NINETEEN Fixed-Price E

- Page 1587 and 1588:

19.6 SECTION NINETEEN differs from

- Page 1589 and 1590:

19.8 SECTION NINETEEN 19.4 ESTIMATI

- Page 1591 and 1592:

19.10 SECTION NINETEEN FIGURE 19.1

- Page 1593 and 1594:

TABLE 19.2 Equipment Ownership and

- Page 1595 and 1596:

19.14 SECTION NINETEEN 2. By time c

- Page 1597 and 1598:

APPENDIX FACTORS FOR CONVERSION TO

- Page 1599 and 1600:

TABLE A.3 Derived SI Units with Spe

- Page 1601 and 1602:

TABLE A.4 Some Common Derived Units

- Page 1603 and 1604:

APPENDIX A.7 mass. In such cases, t

- Page 1605 and 1606:

TABLE A.6 Factors for Conversion to

- Page 1607 and 1608:

APPENDIX A.11 TABLE A.6 Factors for

- Page 1609 and 1610:

APPENDIX A.13 TABLE A.6 Factors for

- Page 1611 and 1612:

Index Terms Links Aggregates: cont.

- Page 1613 and 1614:

Index Terms Links Aluminum: alloys

- Page 1615 and 1616:

Index Terms Links ASD 7.44 (See als

- Page 1617 and 1618:

Index Terms Links Beams: cont. flex

- Page 1619 and 1620:

Index Terms Links Bids: cont. mater

- Page 1621 and 1622:

Index Terms Links Bracing: of beams

- Page 1623 and 1624:

Index Terms Links Building codes (s

- Page 1625 and 1626:

Index Terms Links Cable-supported s

- Page 1627 and 1628:

Index Terms Links Coatings: bibliog

- Page 1629 and 1630:

Index Terms Links Columns: stress-s

- Page 1631 and 1632:

Index Terms Links Concrete: cont. f

- Page 1633 and 1634:

Index Terms Links Concrete admixtur

- Page 1635 and 1636:

Index Terms Links Concrete floors:

- Page 1637 and 1638:

Index Terms Links Connections: cont

- Page 1639 and 1640:

Index Terms Links Construction cont

- Page 1641 and 1642:

Index Terms Links Contractors, home

- Page 1643 and 1644:

Index Terms Links Cost estimates: c

- Page 1645 and 1646:

Index Terms Links Derricks 7.117 De

- Page 1647 and 1648:

Index Terms Links Drinking fountain

- Page 1649 and 1650:

Index Terms Links Electrical circui

- Page 1651 and 1652:

Index Terms Links Elevators: cont.

- Page 1653 and 1654:

Index Terms Links Emergency egress

- Page 1655 and 1656:

Index Terms Links Fire: cont. elect

- Page 1657 and 1658:

Index Terms Links Floor fill 5.5 Fl

- Page 1659 and 1660:

Index Terms Links Foundations: basi

- Page 1661 and 1662:

Index Terms Links Furring 11.49 11.

- Page 1663 and 1664:

Index Terms Links Gypsumboard: cont

- Page 1665 and 1666:

Index Terms Links Heat: balancing o

- Page 1667 and 1668:

Index Terms Links HVAC: computerize

- Page 1669 and 1670:

Index Terms Links Jambs: door 11.11

- Page 1671 and 1672:

Index Terms Links Lighting: brightn

- Page 1673 and 1674:

Index Terms Links Louvers 13.5 Lrfd

- Page 1675 and 1676:

Index Terms Links Luminaires: candl

- Page 1677 and 1678:

Index Terms Links Matrices: advanta

- Page 1679 and 1680:

Index Terms Links Nominal scale 1.2

- Page 1681 and 1682:

Index Terms Links Pipe: corrosion p

- Page 1683 and 1684:

Index Terms Links Plastics: cont. p

- Page 1685 and 1686:

Index Terms Links Plywood: cont. st

- Page 1687 and 1688:

Index Terms Links Reactors, current

- Page 1689 and 1690:

Index Terms Links Roofing: cont. wa

- Page 1691 and 1692:

Shear: in beams: Index Terms Links

- Page 1693 and 1694:

Index Terms Links Sills: door 11.11

- Page 1695 and 1696:

Index Terms Links Soils: cont. with

- Page 1697 and 1698:

Index Terms Links Spikes 10.54 10.5

- Page 1699 and 1700:

Index Terms Links Steel beams: cont

- Page 1701 and 1702:

Index Terms Links Steel reinforceme

- Page 1703 and 1704:

Index Terms Links Storm water: disp

- Page 1705 and 1706:

Index Terms Links Structural steels

- Page 1707 and 1708:

Index Terms Links Subsurface explor

- Page 1709 and 1710:

Index Terms Links Systems design: c

- Page 1711 and 1712:

Index Terms Links Treads 16.6 16.7

- Page 1713 and 1714:

Index Terms Links Vibrations: cont.

- Page 1715 and 1716:

Index Terms Links Walls: cont. sand

- Page 1717 and 1718:

Index Terms Links Welding: cont. st

- Page 1719 and 1720:

Index Terms Links Windows: cont. st

- Page 1721:

Index Terms Links Wood joists 5.4 1