- Page 2:

Principles of Plant Genetics and Br

- Page 6:

Principles of Plant Genetics and Br

- Page 10:

Industry highlights boxes, vii Indu

- Page 14:

Industry highlights boxes Chapter 1

- Page 18:

Industry highlights box authors Acq

- Page 22:

Plant breeding is an art and a scie

- Page 26:

The author expresses sincere gratit

- Page 32:

Section 1 Historical perspectives a

- Page 36:

4 CHAPTER 1 accomplish astonishing

- Page 40:

6 CHAPTER 1 modifying the crop prod

- Page 44:

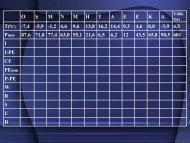

8 CHAPTER 1 Table 1.2 Selected mile

- Page 48:

10 CHAPTER 1 one season. Furthermor

- Page 52:

12 CHAPTER 1 Figure 1 Dr Norman Bor

- Page 56:

14 CHAPTER 1 agrochemicals. Recent

- Page 60:

Section 2 General biological concep

- Page 64:

18 CHAPTER 2 discovered. As will be

- Page 68:

20 CHAPTER 2 antiquity is establish

- Page 72:

22 CHAPTER 2 cultivation in areas a

- Page 76:

24 CHAPTER 2 Table 2.1 Characterist

- Page 80:

26 CHAPTER 2 Table 2.2 An operation

- Page 84:

28 CHAPTER 2 elite germplasm or adv

- Page 88:

30 CHAPTER 2 identify the most prom

- Page 92:

32 CHAPTER 2 Research Institute (SC

- Page 96:

34 CHAPTER 2 Part A Please answer t

- Page 100:

36 CHAPTER 3 out that when plants a

- Page 104:

38 CHAPTER 3 Table 3.2 Number of ch

- Page 108:

40 CHAPTER 3 AA × aa (a) A × a Aa

- Page 112:

42 CHAPTER 3 (a) PP × pp Pp 100% (

- Page 116:

44 CHAPTER 3 AB Ab aB ab (a) Parent

- Page 120:

46 CHAPTER 3 lifeblood of plant bre

- Page 124:

48 CHAPTER 3 -A=T- 5′ 3′ 5′ 5

- Page 128:

50 CHAPTER 3 Expression of genetic

- Page 132:

52 CHAPTER 3 Enhancer region subuni

- Page 136:

54 CHAPTER 3 Part A Please answer t

- Page 140:

56 CHAPTER 4 may be capable of self

- Page 144:

58 CHAPTER 4 Death Seed Reproductiv

- Page 148:

60 CHAPTER 4 Table 4.1 Pollination

- Page 152:

62 CHAPTER 4 homozygous and therefo

- Page 156:

64 CHAPTER 4 price of hybrid seed.

- Page 160:

66 CHAPTER 4 (a) (b) Figure 1 (a) A

- Page 164:

68 CHAPTER 4 only the desired polle

- Page 168:

70 CHAPTER 4 used to make a self-in

- Page 172:

72 CHAPTER 4 Male-fertile RfRf or R

- Page 176:

Section 3 Germplasm issues Chapter

- Page 180:

76 CHAPTER 5 Kingdom Division Class

- Page 184:

78 CHAPTER 5 may be classified into

- Page 188:

80 CHAPTER 5 plant breeding. As pre

- Page 192:

82 CHAPTER 5 both DNA strands; and

- Page 196:

84 CHAPTER 5 100% 50% (a) 100% 50%

- Page 200:

86 CHAPTER 5 Part B Please answer t

- Page 204:

88 CHAPTER 6 programs is the steady

- Page 208:

90 CHAPTER 6 What is genetic vulner

- Page 212:

92 CHAPTER 6 Table 1 Conservation m

- Page 216:

94 CHAPTER 6 Table 3 Varieties regi

- Page 220:

96 CHAPTER 6 linkage maps and a new

- Page 224:

98 CHAPTER 6 Approaches to germplas

- Page 228:

100 CHAPTER 6 resources. Curators o

- Page 232:

102 CHAPTER 6 difficult for users t

- Page 236:

104 CHAPTER 6 and Agricultural Orga

- Page 240:

106 CHAPTER 6 Table 6.2 Germplasm h

- Page 244:

Section 4 Genetic analysis in plant

- Page 248:

110 CHAPTER 7 underlying genetic co

- Page 252:

112 CHAPTER 7 of genes as 1 : n : n

- Page 256:

114 CHAPTER 7 may be toxic in addit

- Page 260:

116 CHAPTER 7 any male gamete of th

- Page 264:

118 CHAPTER 7 B C D E A B C E A I I

- Page 268:

120 CHAPTER 7 heterozygous plants g

- Page 272:

122 CHAPTER 8 2 Absence of linkage.

- Page 276:

124 CHAPTER 8 Table 8.2 As the numb

- Page 280:

126 CHAPTER 8 pollen from a random

- Page 284:

128 CHAPTER 8 environmental varianc

- Page 288:

130 CHAPTER 8 This estimate is fair

- Page 292:

132 CHAPTER 8 in a decline in both

- Page 296:

134 CHAPTER 8 Tandem selection In t

- Page 300:

136 CHAPTER 8 day. This process was

- Page 304:

138 CHAPTER 8 Frequency (%) 40 30 2

- Page 308:

140 CHAPTER 8 ability, the procedur

- Page 312:

142 CHAPTER 8 family are evaluated,

- Page 316:

144 CHAPTER 8 A × B A F2 B F2 A F2

- Page 320:

Purpose and expected outcomes Stati

- Page 324:

148 CHAPTER 9 Concept of statistica

- Page 328:

150 CHAPTER 9 Using data in Table 9

- Page 332: 152 CHAPTER 9 Covariance =−2.45 C

- Page 336: 154 CHAPTER 9 were drawn follow the

- Page 340: 156 CHAPTER 9 Table 1 Summary of th

- Page 344: 158 CHAPTER 9 PC2 1.2 0.8 0.4 0.0 -

- Page 348: 160 CHAPTER 9 Label CASE 0 5 10 15

- Page 352: 162 CHAPTER 9 Part A Please answer

- Page 356: Purpose and expected outcomes One o

- Page 360: 166 CHAPTER 10 developed. This is e

- Page 364: 168 CHAPTER 10 Application of polle

- Page 368: 170 CHAPTER 10 genes are so tightly

- Page 372: 172 CHAPTER 10 The purpose of these

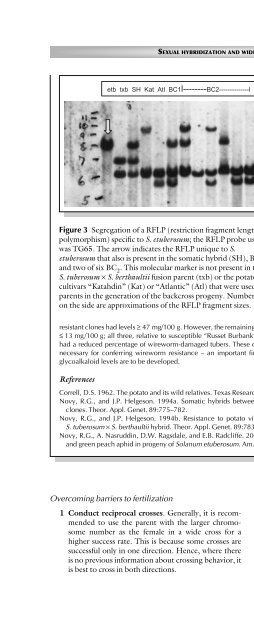

- Page 376: 174 CHAPTER 10 Richard Novy Industr

- Page 380: 176 CHAPTER 10 Tubers of BC 2 gener

- Page 386: R. C. Buckner and his colleagues su

- Page 390: Purpose and expected outcomes The c

- Page 394: TISSUE CULTURE AND THE BREEDING OF

- Page 398: previously described. Sometimes, to

- Page 402: fraction of androgenic grains devel

- Page 406: Introduction Sergey Chalyk TISSUE C

- Page 410: TISSUE CULTURE AND THE BREEDING OF

- Page 414: TISSUE CULTURE AND THE BREEDING OF

- Page 418: only be maintained by vegetative pr

- Page 422: Sexually reproductive Apomict New c

- Page 426: Purpose and expected outcomes It wa

- Page 430: the same plant. However, the dual c

- Page 434:

1 The ends of the segment may be di

- Page 438:

mutagen frequency is desired, the e

- Page 442:

Introduction F. Laurens MUTAGENESIS

- Page 446:

Climatic adaptation MUTAGENESIS IN

- Page 450:

MUTAGENESIS IN PLANT BREEDING 211 K

- Page 454:

Part A Please answer the following

- Page 458:

Triticum monococcum (2n = 2x = 14)

- Page 462:

(a) (b) A B A B a b a b A B A B a b

- Page 466:

Table 13.4 Genetics of autoploids.

- Page 470:

of sterility because of the odd chr

- Page 474:

(a) (b) (c) Figure 1 (a) Germinated

- Page 478:

Figure 2 In vitro regenerated plant

- Page 482:

(AABBDDRR, 2n = 8x = 56), but it re

- Page 486:

(in alloploids) or homologous (in a

- Page 490:

Purpose and expected outcomes Genes

- Page 494:

and expression (including codon usa

- Page 498:

1 Efficient plant regeneration syst

- Page 502:

Structural defect in the gene const

- Page 506:

sequence analysis. It is an applica

- Page 510:

Analysis BIOTECHNOLOGY IN PLANT BRE

- Page 514:

BIOTECHNOLOGY IN PLANT BREEDING 243

- Page 518:

of genes of known functions. Three

- Page 522:

source of the gene is a wild germpl

- Page 526:

ands for identification may minimiz

- Page 530:

location, genetic effects, and the

- Page 534:

3 Germplasm evaluation. Markers can

- Page 538:

Engineering pest resistance To date

- Page 542:

Purpose and expected outcomes Intel

- Page 546:

the key functions of a patent is to

- Page 550:

The development of truly new and un

- Page 554:

Ethics in plant breeding Manipulati

- Page 558:

Introduction ISSUES IN THE APPLICAT

- Page 562:

ISSUES IN THE APPLICATION OF BIOTEC

- Page 566:

Overview of the regulation of the U

- Page 570:

Table 15.2 Some viral-coated protei

- Page 574:

conditions. Further, these phenotyp

- Page 578:

there is no inherent health risk in

- Page 582:

esistance concerns (or “collatera

- Page 586:

Damage to economic interest (market

- Page 590:

Section 6 Classic methods of plant

- Page 594:

Open-pollinated cultivars Contrary

- Page 598:

Common plant breeding notations Pla

- Page 602:

(a) Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 (b) Source

- Page 606:

2 Cultivars developed for a discrim

- Page 610:

especially where readily identifiab

- Page 614:

Comments 1 Growing parents, making

- Page 618:

Comments Generation Year 1 P 1 × P

- Page 622:

3 Natural selection may increase fr

- Page 626:

5 Every plant originates from a dif

- Page 630:

1 year BREEDING SELF-POLLINATED SPE

- Page 634:

BREEDING SELF-POLLINATED SPECIES 30

- Page 638:

Year 1 Year 2 F 1 Year 3 Year 4 Yea

- Page 642:

2 Extensive advanced testing is not

- Page 646:

Applications One of the earliest ap

- Page 650:

species (maize) and has been a majo

- Page 654:

Purpose and expected outcomes As pr

- Page 658:

epistatic interactions enhance the

- Page 662:

Season 1 Source population C 0 Seas

- Page 666:

Procedure: cycle 1 This is the same

- Page 670:

Advantages and disadvantages The ma

- Page 674:

(a) (b) Figure 1 Examples of (a) Po

- Page 678:

Figure 3 Range of seed development

- Page 682:

Applications The scheme has been us

- Page 686:

stems from several biological facto

- Page 690:

Factors affecting the performance o

- Page 694:

7 Give a specific disadvantage of m

- Page 698:

Other notable advances in the breed

- Page 702:

BREEDING HYBRID CULTIVARS 337 ducin

- Page 706:

BREEDING HYBRID CULTIVARS 339 for c

- Page 710:

of interest. As Falconer indicated,

- Page 714:

patterns derived from the same open

- Page 718:

(a) (b) Seed parent (male-sterile)

- Page 722:

Table 18.1 Calculating heat units a

- Page 726:

such as sugarcane (most commercial

- Page 730:

Section 7 Selected breeding objecti

- Page 734:

water utilization, photoperiod, har

- Page 738:

expense of the rest of the plant. N

- Page 742:

usually results from one component

- Page 746:

Figure 3 Field trials demonstrating

- Page 750:

References Concept of yield plateau

- Page 754:

Shatter-sensitive cultivars are sus

- Page 758:

Nature, types, and economic importa

- Page 762:

Purpose and expected outcomes Plant

- Page 766:

elative to a benchmark. A genotype

- Page 770:

Types of genetic resistance The com

- Page 774:

General considerations for breeding

- Page 778:

for most middling resistance. It sh

- Page 782:

pathogen to give resistance), was c

- Page 786:

BREEDING FOR RESISTANCE TO DISEASES

- Page 790:

BREEDING FOR RESISTANCE TO DISEASES

- Page 794:

5 The plant or cell overproduces th

- Page 798:

Purpose and expected outcomes Clima

- Page 802:

ultimately its productivity and eco

- Page 806:

Breeding for drought resistance Dro

- Page 810:

drought. Consequently, phenotypic s

- Page 814:

BREEDING FOR RESISTANCE TO ABIOTIC

- Page 818:

More N partitioned to leaves before

- Page 822:

interruption in normal germination,

- Page 826:

Table 21.1 Relative salt tolerance

- Page 830:

toxicities of economic importance t

- Page 834:

Acevedo, E., and E. Fereres. 1993.

- Page 838:

Table 22.1 Essential amino acids th

- Page 842:

BREEDING COMPOSITIONAL TRAITS AND A

- Page 846:

Figure 1 Farmer (left) and research

- Page 850:

the presence of β-carotene, but no

- Page 854:

and cell walls are degraded. There

- Page 858:

milling, extraction of oil, starch

- Page 862:

Section 8 Cultivar release and comm

- Page 866:

in two stages. The first stage, cal

- Page 870:

genotype is reduced. This raises th

- Page 874:

Different models of ANOVA are used

- Page 878:

Table 23.2 Stability analysis. PERF

- Page 882:

PERFORMANCE EVALUATION FOR CROP CUL

- Page 886:

esources available (land, seed, lab

- Page 890:

Advantages 1 It is the simplest of

- Page 894:

Mapping populations have additional

- Page 898:

Purpose and expected outcomes The u

- Page 902:

Funk Columbiana Farm Seed Germain

- Page 906:

Joe W. Burton SEED CERTIFICATION AN

- Page 910:

Registered seed Registered seed is

- Page 914:

Canada’s Plant Breeders’ Rights

- Page 918:

Seed certification process There ar

- Page 922:

Table 24.1 Information on a seed ta

- Page 926:

Boswell, V.R. 1961. The importance

- Page 930:

property is a major one in plant br

- Page 934:

important issues to be considered i

- Page 938:

Soybean Soybean research is conduct

- Page 942:

INTERNATIONAL PLANT BREEDING EFFORT

- Page 946:

Selected accomplishments The impact

- Page 950:

national entities. More importantly

- Page 954:

Cicarelli contest that most farmers

- Page 958:

EMERGING CONCEPTS IN PLANT BREEDING

- Page 962:

EMERGING CONCEPTS IN PLANT BREEDING

- Page 966:

Principles of organic plant breedin

- Page 970:

Part II Breeding selected crops Cha

- Page 974:

Adaptation Wheat is best adapted to

- Page 978:

are less successful, being of poor

- Page 982:

Introduction BREEDING WHEAT 477 Ind

- Page 986:

Host plant resistance to disease an

- Page 990:

Greenhouse nursery Breeders may use

- Page 994:

when the production area is isolate

- Page 998:

Taxonomy Kingdom Plantae Subkingdom

- Page 1002:

encloses the soft starch at the cen

- Page 1006:

Designated ms 1 , ms 2 ,...ms n , o

- Page 1010:

F. J. Betrán Texas A&M University,

- Page 1014:

Development of hybrids BREEDING COR

- Page 1018:

chambers may be used for experiment

- Page 1022:

orer. A chemical found in corn with

- Page 1026:

A British sea captain brought rice

- Page 1030:

while awnless is conditioned by an

- Page 1034:

Figure 1 Rice panicle being prepare

- Page 1038:

Figure 5 A foundation seed field of

- Page 1042:

emoved with forceps, the cut may be

- Page 1046:

Taxonomy Kingdom Plantae Subkingdom

- Page 1050:

green midrib because of the presenc

- Page 1054:

BREEDING SORGHUM 513 Kansas State U

- Page 1058:

Summer Year 5 Summer Year 7 Summer

- Page 1062:

covered with the bag. Pollination s

- Page 1066:

Taxonomy Kingdom Plantae Subkingdom

- Page 1070:

and brown being dominant over gray.

- Page 1074:

BREEDING SOYBEAN 523 easily selecte

- Page 1078:

BREEDING SOYBEAN 525 An advantage o

- Page 1082:

Common breeding objectives 1 Grain

- Page 1086:

Taxonomy Kingdom Plantae Subkingdom

- Page 1090:

Program objectives Charles Simpson

- Page 1094:

BREEDING PEANUT 533 lines in hopes

- Page 1098:

for emasculation, which is done in

- Page 1102:

Taxonomy Kingdom Plantae Subkingdom

- Page 1106:

Evolution of the modern potato crop

- Page 1110:

BREEDING POTATO 541 Table 1 The Sco

- Page 1114:

(berries) called potato balls. The

- Page 1118:

6 Potato tuber quality improvement.

- Page 1122:

grown in America, Africa, Asia, and

- Page 1126:

Introduction Don L. Keim BREEDING C

- Page 1130:

BREEDING COTTON 551 are grown in tr

- Page 1134:

economically important traits has b

- Page 1138:

Part B Please answer the following

- Page 1142:

Central dogma: The underlying model

- Page 1146:

Mitosis: The process of nuclear div

- Page 1150:

Chapter 1 http://www.foodfirst.org/

- Page 1154:

Imperial unit Metric conversion Vol

- Page 1158:

complex inheritance, 42 composite c

- Page 1162:

minor gene resistance, 371 minor ge

- Page 1166:

technology protection system (TPS),