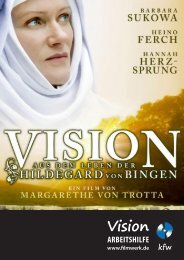

A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen

Beverly Mayne Kienzle, Debra L. Stoudt & George Ferzoco, "A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen". BRILL, Leiden - Boston, 2014.

Beverly Mayne Kienzle, Debra L. Stoudt & George Ferzoco, "A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen". BRILL, Leiden - Boston, 2014.

- TAGS

- hildegard-of-bingen

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

116 justin a. s<strong>to</strong>ver<br />

more recently John Van Engen has defended them as genuine.31 They<br />

have been presumed <strong>to</strong> be by the same author, but in a century with so<br />

many Master Odos, this assertion needs further evidence, and preliminary<br />

assessments would cast some doubt on this identifijication.32 The dating<br />

<strong>of</strong> the letters is also far less certain than usually supposed. In 1148, at<br />

the consis<strong>to</strong>ry following the council <strong>of</strong> Reims (the same council in which<br />

<strong>Hildegard</strong>’s own works were reputedly discussed),33 Gilbert, the bishop<br />

<strong>of</strong> Poitiers, was put on trial at the instigation <strong>of</strong> Bernard <strong>of</strong> Clairvaux for<br />

holding (among other things) that God’s paternity and divinity are not<br />

identical with him. Based on the (pseudo-)Augustinian axiom “Whatever<br />

is in God is God,”34 the consis<strong>to</strong>ry required Gilbert <strong>to</strong> clarify his proposition.<br />

This same proposition is put <strong>to</strong> <strong>Hildegard</strong> by Odo <strong>of</strong> Paris in Letter<br />

40, and part <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hildegard</strong>’s answer mirrors the auc<strong>to</strong>ritas used by Bernard<br />

and his allies at the council, “What is in God is God.” Marianna Schrader<br />

and Adelgundis Führkötter fijirst suggested the connection <strong>of</strong> this letter <strong>to</strong><br />

the council, arguing for a date around 1148, and their arguments have been<br />

accepted by most scholars.35 Van Engen and Mews consider this letter <strong>to</strong><br />

31 See Van Acker’s introduction in Epis<strong>to</strong>larium, I, pp. xii–xiii. Van Engen analyses these<br />

letters and defends their authenticity in “Letters and the Public Persona <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hildegard</strong>,” in<br />

Umfeld, pp. 393–95.<br />

32 The strongest argument in favor <strong>of</strong> the identifijication is that Odo <strong>of</strong> Soissons is known<br />

<strong>to</strong> have taught at Paris. The arguments against the identifijication are nonetheless numerous:<br />

the two letters do not appear <strong>to</strong>gether in any <strong>of</strong> the manuscripts; the salutations and<br />

valedictions <strong>of</strong> the two letters are entirely diffferent; and their styles are quite distinct,<br />

with Odo <strong>of</strong> Soissons’s phrased in relatively short sentences with conventional word order,<br />

and Odo <strong>of</strong> Paris’s consisting <strong>of</strong> a small number <strong>of</strong> densely constructed periods, with a<br />

liberal use <strong>of</strong> absolute constructions. The prose cursus <strong>of</strong> the two letters also difffer: Odo<br />

<strong>of</strong> Soissons consistently uses a tardus for full s<strong>to</strong>ps and a planus for both partial s<strong>to</strong>ps<br />

and major divisions, while Odo <strong>of</strong> Paris is much less consistent in his prose rhythm but<br />

does tend <strong>to</strong> use a tardus at full s<strong>to</strong>ps and a velox at partial s<strong>to</strong>ps. Beyond these stylistic<br />

diffferences, the content <strong>of</strong> the letters and the personae <strong>of</strong> the authors have little in common<br />

with one another. On the various Odos (36 by one count) <strong>of</strong> the schools <strong>of</strong> the 12th<br />

century, see Gillian Evans, “The Place <strong>of</strong> Odo <strong>of</strong> Soissons’ Quaestiones. Problem-Solving in<br />

Mid-Twelfth-Century Bible Study and Some Matters <strong>of</strong> Language and Logic,” Recherches<br />

de théologie ancienne et médiévale 49 (1982): 127. To maintain an agnostic stance on the<br />

question, this paper will follow the manuscripts in identifying the author <strong>of</strong> Letter 39 as<br />

Odo <strong>of</strong> Soissons and the author <strong>of</strong> Letter 40 as Odo <strong>of</strong> Paris.<br />

33 See Van Engen, “Letters,” pp. 385–86.<br />

34 On this axiom, see most recently and comprehensively the article by Luisa Valente,<br />

“Alla ricerca dell’au<strong>to</strong>rità perduta: ‘Quidquid est in Deo, Deus est,’ ” Medioevo 25 (1999): 713–<br />

38; along with Lauge Olaf Nielsen, Theology and Philosophy in the Twelfth Century: A Study<br />

<strong>of</strong> Gilbert Porreta’s Thinking and the Theological Expositions <strong>of</strong> the Doctrine <strong>of</strong> the Incarnation<br />

During the Period 1130–1180 (Leiden, 1982), p. 60, n. 96.<br />

35 Marianna Schrader and Adelgundis Führkötter. Die Echtheit des Schrifttums der heiligen<br />

<strong>Hildegard</strong> von <strong>Bingen</strong>: quellenkritische Untersuchungen (Cologne, 1956), pp. 172–73.