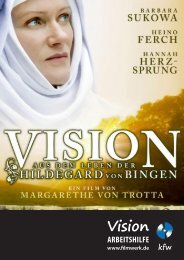

A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen

Beverly Mayne Kienzle, Debra L. Stoudt & George Ferzoco, "A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen". BRILL, Leiden - Boston, 2014.

Beverly Mayne Kienzle, Debra L. Stoudt & George Ferzoco, "A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen". BRILL, Leiden - Boston, 2014.

- TAGS

- hildegard-of-bingen

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

intertextuality in hildegard’s works 143<br />

While the lion signifijies monks, the calf represents priests.27 <strong>Hildegard</strong><br />

urges chastity and sobriety on priests.28 The magistra’s appeals for chastity<br />

echo the message <strong>of</strong> the Gregorian reforms and her own admonitions<br />

<strong>to</strong> the clergy in Scivias and subsequent writings.29<br />

From the lion and the calf, monks and priests, <strong>Hildegard</strong> moves <strong>to</strong><br />

those “whom they call” conversi, that is, the lay brothers who worked<br />

for the monastery.30 She says that “many <strong>of</strong> them do not truly turn their<br />

ways <strong>to</strong> God, but they value contrariness over rectitude and address<br />

their superiors arrogantly, saying: ‘Who are they and what are these? And<br />

what were we, or what are we?’”31 She concludes that they are like pseudoprophets,<br />

and she discusses the difffering responsibilities <strong>of</strong> priests and<br />

farmers, teachers, and masters as part <strong>of</strong> the divine order.32 <strong>Hildegard</strong><br />

enjoins the magistri <strong>of</strong> the lay brothers with the duty <strong>of</strong> reproaching and<br />

correcting the conversi, “who refuse <strong>to</strong> work, and serve neither God nor<br />

the world with perfection.”33 Mixing these divinely ordained roles is analogous,<br />

she says, <strong>to</strong> pitting the symbolic roles <strong>of</strong> the four creatures against<br />

each other.34 <strong>Hildegard</strong> sees the ambiguous status <strong>of</strong> lay brothers as a<br />

risky impediment <strong>to</strong> spiritual life; the mixed character <strong>of</strong> their position in<br />

the monastery seems <strong>to</strong> threaten its stability.35<br />

Was <strong>Hildegard</strong> addressing a specifijic situation at Eberbach? The fijirst<br />

known revolt <strong>of</strong> Cistercian lay brothers occurred in 1168 at Schönau, near<br />

Heidelberg, hence not long before this letter was written.36 She specifijically<br />

mentions the lay brothers’ refusal <strong>to</strong> work. Other letters exchanged<br />

between <strong>Hildegard</strong> and the monks at Eberbach shed some light on<br />

27 Letters, 1, 84R, p. 186; Epis<strong>to</strong>larium, I, 84R, p. 194, ll. 162–65.<br />

28 Letters, 1, 84R, p. 186; Epis<strong>to</strong>larium, I, 84R, p. 194, ll. 166–71.<br />

29 Speaking New Mysteries, pp. 26–30, 252–54.<br />

30 James France discusses this letter in Separate but Equal: Cistercian Lay Brothers 1120–<br />

1350 (Trappist, Ky., 2012), pp. 281–85.<br />

31 Letters, 1, 84R, p. 186; Epis<strong>to</strong>larium, I, 84R, pp. 194–95, ll. 174–79: “ipsi conuersos<br />

uocant, quorum plurimi se ad Deum in moribus suis non conuertunt ueraciter, quia contrarietatem<br />

potius quam rectitudinem diligunt et opera sua cum sono temeritatis agunt, de<br />

prelatis suis sic dicentes: Qui sunt et quid sunt isti? Et quid fuimus aut quid sumus nos?”<br />

32 Letters, 1, 84R, p. 187; Epis<strong>to</strong>larium, I, 84R, p. 195, ll. 198–207.<br />

33 Letters, 1, 84R, p. 187; Epis<strong>to</strong>larium, I, 84R, pp. 195–96, ll. 208–24, at p. 196, ll. 220–21:<br />

“nec in die nec in nocte operatur, quoniam nec Deo nec seculo ad perfectum seruiunt.”<br />

34 Letters, 1, 84R, p. 187; Epis<strong>to</strong>larium, I, 84R, p. 197, ll. 214–16.<br />

35 <strong>Hildegard</strong> was opposed <strong>to</strong> mixing social classes in the same community, and she<br />

incurred the ire <strong>of</strong> her Augustinian contemporary, Tenxwind, for the trappings <strong>of</strong> social<br />

status that she allowed her nuns. See Speaking New Mysteries, pp. 32–33.<br />

36 On Cistercian lay brothers, see Brian Noell, “Expectation and Unrest among Cistercian<br />

Lay Brothers in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries,” Journal <strong>of</strong> Medieval His<strong>to</strong>ry 32<br />

(2006): 253–74, and the various works cited there.