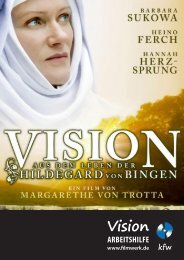

A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen

Beverly Mayne Kienzle, Debra L. Stoudt & George Ferzoco, "A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen". BRILL, Leiden - Boston, 2014.

Beverly Mayne Kienzle, Debra L. Stoudt & George Ferzoco, "A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen". BRILL, Leiden - Boston, 2014.

- TAGS

- hildegard-of-bingen

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

intertextuality in hildegard’s works 145<br />

The magistra provides an extended description <strong>of</strong> these pious laypersons<br />

and their eternal reward, emphasizing their commitment <strong>to</strong> selfexamination<br />

and penitence.44<br />

The fourth animal, the flying eagle, represents people living in the<br />

world and leading a secular life: those who rise up <strong>to</strong> abstinence, casting<br />

aside their sin, like Mary Magdalene, who chose “the best part”<br />

(Lk. 10:42).45 Here <strong>Hildegard</strong> blends, as other medieval writers did, the<br />

repentant woman sinner (Lk. 7:37–50) and Mary <strong>of</strong> Magdala (Mk. 16:9)<br />

with Mary <strong>of</strong> Bethany.46 In two <strong>of</strong> the Expositiones, the magistra glosses<br />

Mary Magdalene as peccatrix penitens.47 Letter 84R is distinctive from these<br />

other references, in that <strong>Hildegard</strong> afffijirms the role <strong>of</strong> Mary Magdalene as<br />

a model for penitent laypeople.<br />

The magistra concludes the letter stating in the fijirst person: “But I, a<br />

poor little form, weak and sickly since childhood, was compelled <strong>to</strong> write<br />

this text, by a mystical and true vision, lying in bed seriously ill, with God<br />

helping and commanding.”48 The phrase that <strong>Hildegard</strong> uses <strong>to</strong> describe<br />

her seeing, in mystica et uera uisione, is nearly identical <strong>to</strong> what that she<br />

employs elsewhere for Ezekiel’s vision: in mystica uisione.49 The magistra<br />

combines this fijigure <strong>of</strong> strength, hidden in the weakness <strong>of</strong> her female<br />

form, with an admonishment <strong>to</strong> prelates and teachers as well as a threat<br />

<strong>of</strong> God’s punishment (uindicta Dei) for any who fail <strong>to</strong> heed her words.50<br />

quasi cum pennis uolent, quia queque bona desideria sicut radius solis ex cordi iusti emittuntur,<br />

unde et uelut pennata uidentur.”<br />

44 Letters, 1, 84R, p. 189; Epis<strong>to</strong>larium, I, 84R, pp. 198–99, ll. 285–347.<br />

45 Letters, 1, 84R, p. 190; Epis<strong>to</strong>larium, I, 84R, pp. 199–200, ll. 348–65.<br />

46 This began with Gregory the Great’s fusion <strong>of</strong> the three Marys and became the standard<br />

for medieval exegetes. See Gregory the Great, Homiliae in Hiezechihelem prophetam,<br />

II, 8.21, p. 352, ll. 589–92: “In hoc fonte misericordiae lota est Maria Magdalene, quae prius<br />

famosa peccatrix, postmodum lavit maculas lacrimis, detersit maculas corrigendo mores.”<br />

Gregory the Great, Homiliae in evangelia, ed. R. Étaix (Turnhout, 1999), II, 25, pp. 215–16, ll.<br />

285–314. Three biblical women become one: an unnamed sinner who washed Jesus’ feet<br />

with her hair (Lk. 7:37–50); Mary <strong>of</strong> Bethany, who called upon Jesus <strong>to</strong> raise her brother<br />

Lazarus from the dead (Jn. 11:1–45; 12:1–8); and Mary Magdalene, apostle <strong>to</strong> the apostles,<br />

whom Jesus healed <strong>of</strong> seven demons (Mk. 16:9). See Katherine Ludwig Jansen, The Making<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Magdalen: Preaching and Popular Devotion in the Later Middle Ages (Prince<strong>to</strong>n,<br />

2000), pp. 32–35.<br />

47 Expo. Euang., 28, p. 269, ll. 1–2; Ibid., 29, p. 272, ll. 1–3. <strong>Hildegard</strong>, however, does not<br />

dwell on the Magdalene, neither here nor in her other writings.<br />

48 Letters, 1, 84R, p. 191; Epis<strong>to</strong>larium, I, 84R, p. 201, ll. 397–99: “Ego autem paupercula<br />

forma, ab infantia mea debilis et infijirma, in mystica et uera uisione ad hanc scripturam<br />

coacta sum, eamque in graui egritudine in lec<strong>to</strong> iacens, Deo iubente et adiuuante, conscripsi.”<br />

See also p. 196, ll. 225–26, cited above in note 38.<br />

49 See Scivias 2.4, p. 170, ll. 403–04: “ut in mystica uisione sua Ezekiel dicit.”<br />

50 Letters, 1, 84R, p. 191; Epis<strong>to</strong>larium, I, 84R, p. 201, ll. 400–05. See Speaking New Mysteries,<br />

p. 6, on <strong>Hildegard</strong>’s visionary claims and the lack there<strong>of</strong> in the Expositiones.