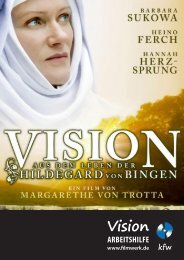

A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen

Beverly Mayne Kienzle, Debra L. Stoudt & George Ferzoco, "A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen". BRILL, Leiden - Boston, 2014.

Beverly Mayne Kienzle, Debra L. Stoudt & George Ferzoco, "A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen". BRILL, Leiden - Boston, 2014.

- TAGS

- hildegard-of-bingen

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

122 justin a. s<strong>to</strong>ver<br />

For <strong>Hildegard</strong>, witchcraft is the abuse <strong>of</strong> philosophy. Playing on the double<br />

identifijication <strong>of</strong> Mercury as planet and philosopher,60 <strong>Hildegard</strong> claims<br />

that the ancient sages, having received some knowledge from God and<br />

some from devils, learned <strong>to</strong> manipulate nature through magical means.61<br />

But the divine voice responds <strong>to</strong> this image:<br />

Man is living on the wings <strong>of</strong> rationality . . . But you, o magical art, have a<br />

circle without a point. For when you make many inquiries in the circle <strong>of</strong><br />

creation, creation itself will deprive you <strong>of</strong> honor and riches and will cast<br />

you like a s<strong>to</strong>ne in<strong>to</strong> hell, for you s<strong>to</strong>le the name <strong>of</strong> God for yourself.62<br />

This phrase circulum absque punc<strong>to</strong> is immediately familiar as the reverse<br />

<strong>of</strong> the punctum absque circulo in her letter <strong>to</strong> Odo. Magic manipulates the<br />

efffects <strong>of</strong> created things while denying their concomitant cause in God.<br />

Conversely, academic theologians like Gilbert acknowledge God but deny<br />

his concomitant identity with his divinity and paternity. All <strong>of</strong> them abuse<br />

their rationality.<br />

<strong>Hildegard</strong>’s “Scholastic” Works<br />

In the letters and discourses already discussed, <strong>Hildegard</strong> attempts <strong>to</strong><br />

demonstrate <strong>to</strong> the masters how they ought <strong>to</strong> conduct their scholarship.<br />

sime reperierunt. Hec fortissimi et sapientissimi uiri ex parte a Deo, et ex parte a malignis<br />

spiritibus adinuenerunt. Et quid hoc obfuit? Et sic se ipsos planetas nominauerunt, quoniam<br />

de sole et de luna et de stellis plurimam sapientiam ac multas inquisitiones acceperunt. Ego<br />

autem ubicumque uoluero, in artibus istis regno et dominor: scilicet in luminaribus celi, in<br />

arboribus et in herbis ac in omnibus uirentibus terre, et in bestiis et in animalibus super<br />

terram, ac in uermibus super terram et subtus terram. Et in itineribus meis quis mihi resistet?<br />

Deus omnia creauit: unde in artibus istis illi nullam iniuriam facio.”<br />

60 That is, Hermes Trismegistus, the legendary author <strong>of</strong> the Asclepius, a text which<br />

was enjoying a considerable revival during this period. See Paolo Lucentini, “L’Asclepius<br />

ermetico nel secolo XII,” in From Athens <strong>to</strong> Chartres, pp. 397–420. <strong>Hildegard</strong> may have had<br />

fijirsthand exposure <strong>to</strong> the Asclepius, as Dronke argues (see “Pla<strong>to</strong>nic-Christian Allegories,”<br />

p. 383, n. 11).<br />

61 Imagining philosophers as magicians is not uncommon in the 12th century—there<br />

circulated, for example, a work reputedly by Pla<strong>to</strong> but translated from the Arabic that was<br />

called the Book <strong>of</strong> the Cow; see David Pingree, “Pla<strong>to</strong>’s Hermetic Book <strong>of</strong> the Cow,” in Il Neopla<strong>to</strong>nismo<br />

nel rinascimen<strong>to</strong>, ed. Pietro Prini (Rome, 1993), pp. 133–45. A number <strong>of</strong> magical<br />

works attributed <strong>to</strong> Aris<strong>to</strong>tle also circulated; see Charles Burnett, “Arabic, Greek and Latin<br />

Works on Astrological Magic attributed <strong>to</strong> Aris<strong>to</strong>tle,” in Pseudo-Aris<strong>to</strong>tle in the Middle Ages,<br />

eds. Jill Kraye, William F. Ryan, and Charles B. Schmitt (London, 1986), pp. 84–96.<br />

62 Vite mer., 5.7, p. 223: “Homo in pennis rationalitatis uitalis est, et omne uolatile ac<br />

reptile ex elementis uiuit et mouetur. Et homo sonum in rationalitate habet; reliqua autem<br />

creatura muta est, nec se ipsam nec alios iuuare potest, sed <strong>of</strong>ffijicium suum perfijicit. Tu<br />

autem, o ars magica, circulum absque punc<strong>to</strong> habes. Nam cum in circulo creature multas<br />

sciscitationes inquiris, ipsa creatura honorem et diuitias tibi abstrahet, et uelut lapidem in<br />

infernum proiciet te, quoniam ipsi nomen Dei sui abstulisti.”