Preventing Childhood Obesity - Evidence Policy and Practice.pdf

Preventing Childhood Obesity - Evidence Policy and Practice.pdf

Preventing Childhood Obesity - Evidence Policy and Practice.pdf

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Chapter 27<br />

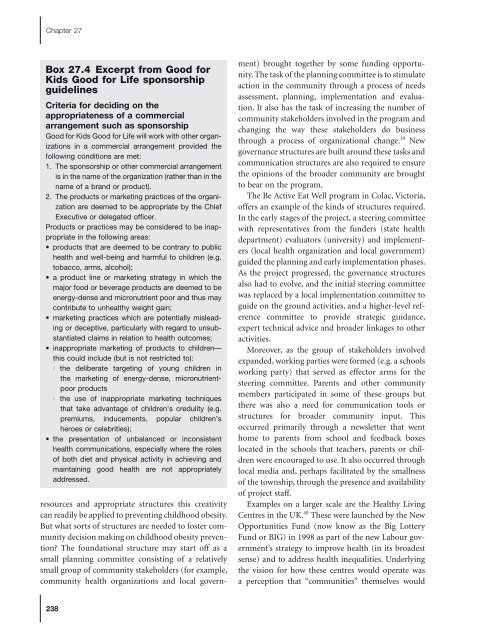

Box 27.4 Excerpt from Good for<br />

Kids Good for Life sponsorship<br />

guidelines<br />

Criteria for d eciding on the<br />

a ppropriateness of a c ommercial<br />

a rrangement s uch a s s ponsorship<br />

Good for Kids Good for Life will work with other organizations<br />

in a commercial arrangement provided the<br />

following conditions are met:<br />

1. The sponsorship or other commercial arrangement<br />

is in the name of the organization (rather than in the<br />

name of a br<strong>and</strong> or product).<br />

2. The products or marketing practices of the organization<br />

are deemed to be appropriate by the Chief<br />

Executive or delegated officer.<br />

Products or practices may be considered to be inappropriate<br />

in the following areas:<br />

• products that are deemed to be contrary to public<br />

health <strong>and</strong> well - being <strong>and</strong> harmful to children (e.g.<br />

tobacco, arms, alcohol);<br />

• a product line or marketing strategy in which the<br />

major food or beverage products are deemed to be<br />

energy - dense <strong>and</strong> micronutrient poor <strong>and</strong> thus may<br />

contribute to unhealthy weight gain;<br />

• marketing practices which are potentially misleading<br />

or deceptive, particularly with regard to unsubstantiated<br />

claims in relation to health outcomes;<br />

• inappropriate marketing of products to children —<br />

this could include (but is not restricted to):<br />

<br />

the deliberate targeting of young children in<br />

the marketing of energy - dense, micronutrient -<br />

poor products<br />

<br />

the use of inappropriate marketing techniques<br />

that take advantage of children ’ s credulity (e.g.<br />

premiums, inducements, popular children ’ s<br />

heroes or celebrities);<br />

• the presentation of unbalanced or inconsistent<br />

health communications, especially where the roles<br />

of both diet <strong>and</strong> physical activity in achieving <strong>and</strong><br />

maintaining good health are not appropriately<br />

addressed.<br />

resources <strong>and</strong> appropriate structures this creativity<br />

can readily be applied to preventing childhood obesity.<br />

But what sorts of structures are needed to foster community<br />

decision making on childhood obesity prevention?<br />

The foundational structure may start off as a<br />

small planning committee consisting of a relatively<br />

small group of community stakeholders (for example,<br />

community health organizations <strong>and</strong> local govern-<br />

ment) brought together by some funding opportunity.<br />

The task of the planning committee is to stimulate<br />

action in the community through a process of needs<br />

assessment, planning, implementation <strong>and</strong> evaluation.<br />

It also has the task of increasing the number of<br />

community stakeholders involved in the program <strong>and</strong><br />

changing the way these stakeholders do business<br />

through a process of organizational change. 39 New<br />

governance structures are built around these tasks <strong>and</strong><br />

communication structures are also required to ensure<br />

the opinions of the broader community are brought<br />

to bear on the program.<br />

The Be Active Eat Well program in Colac, Victoria,<br />

offers an example of the kinds of structures required.<br />

In the early stages of the project, a steering committee<br />

with representatives from the funders (state health<br />

department) evaluators (university) <strong>and</strong> implementers<br />

(local health organization <strong>and</strong> local government)<br />

guided the planning <strong>and</strong> early implementation phases.<br />

As the project progressed, the governance structures<br />

also had to evolve, <strong>and</strong> the initial steering committee<br />

was replaced by a local implementation committee to<br />

guide on the ground activities, <strong>and</strong> a higher - level reference<br />

committee to provide strategic guidance,<br />

expert technical advice <strong>and</strong> broader linkages to other<br />

activities.<br />

Moreover, as the group of stakeholders involved<br />

exp<strong>and</strong>ed, working parties were formed (e.g. a schools<br />

working party) that served as effector arms for the<br />

steering committee. Parents <strong>and</strong> other community<br />

members participated in some of these groups but<br />

there was also a need for communication tools or<br />

structures for broader community input. This<br />

occurred primarily through a newsletter that went<br />

home to parents from school <strong>and</strong> feedback boxes<br />

located in the schools that teachers, parents or children<br />

were encouraged to use. It also occurred through<br />

local media <strong>and</strong>, perhaps facilitated by the smallness<br />

of the township, through the presence <strong>and</strong> availability<br />

of project staff.<br />

Examples on a larger scale are the Healthy Living<br />

Centres in the UK. 40 These were launched by the New<br />

Opportunities Fund (now know as the Big Lottery<br />

Fund or BIG) in 1998 as part of the new Labour government<br />

’ s strategy to improve health (in its broadest<br />

sense) <strong>and</strong> to address health inequalities. Underlying<br />

the vision for how these centres would operate was<br />

a perception that “ communities ” themselves would<br />

238