motivational analysis of organizations

motivational analysis of organizations

motivational analysis of organizations

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

working with. If they work with machines, they will get greasy; if they work with<br />

people, they will become involved.<br />

Abstract Life Experiencing<br />

People who prefer this style have no special desire to touch, but they want to keep active<br />

by thinking about the situation and relating it to similar situations. Their preferred<br />

interaction style is internal—inside their own heads.<br />

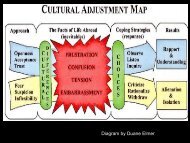

The Four Learning Domains<br />

A person is unlikely to be on the extreme end <strong>of</strong> either axis, and no one type <strong>of</strong> learning<br />

is “best.” Any mixture <strong>of</strong> preferences simply represents a person’s uniqueness. The<br />

model is useful in helping people differentiate themselves, and it <strong>of</strong>fers a method for<br />

looking at the way different styles fit together. This section describes the four domains<br />

that are represented in the model.<br />

The descriptions <strong>of</strong> these domains could be <strong>of</strong> special interest to managers, because<br />

they will help the manager understand the relationship between managerial action and<br />

learning style. A manager should be capable <strong>of</strong> learning and functioning well in all four<br />

domains, especially if he or she expects to face a variety <strong>of</strong> situations and challenges.<br />

The successful manager is likely to be the one who can operate in both a task and a<br />

people environment with the ability to see and become involved with the concrete and<br />

also use thought processes to understand what is needed. The normative assumption <strong>of</strong><br />

the model is that a manager should learn how to learn in each <strong>of</strong> the four domains. In<br />

doing this, the manager may well build on his or her primary strengths; but the<br />

versatility and flexibility demanded in a managerial career make clear the importance <strong>of</strong><br />

all four domains.<br />

Domain I, the Thinking Planner. A combination <strong>of</strong> cognitive and abstract<br />

preferences constitutes domain I, where the “thinking planner” is located. This domain<br />

might well be termed the place for the planner whose job is task oriented and whose<br />

environment contains primarily things, numbers, or printouts. The bias in formal<br />

education is <strong>of</strong>ten toward this learning domain, and Mintzberg (1976) was critical <strong>of</strong> this<br />

bias. In this domain things are treated abstractly, and <strong>of</strong>ten their socioemotional<br />

elements are denied.<br />

The domain-I learner should do well in school, should have a talent for planning,<br />

and is likely to be successful as a staff person or manager in a department that deals with<br />

large quantities <strong>of</strong> untouchable things. This domain represents an important area for<br />

management learning. Of the four domains, it seems to receive the heaviest emphasis in<br />

traditional university programs and in management-development seminars, particularly<br />

those in financial management.<br />

Domain II, the Feeling Planner: A combination <strong>of</strong> affective and abstract<br />

preferences constitutes domain II, where the “feeling planner” is located. The<br />

managerial style associated with this domain is that <strong>of</strong> the thinker who can learn and<br />

The Pfeiffer Library Volume 19, 2nd Edition. Copyright © 1998 Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer ❚❘ 63