- Page 1 and 2:

Air Toxics Hot Spots Program Risk A

- Page 3 and 4:

Prepared by: John D. Budroe, Ph.D.

- Page 5 and 6:

This document is one of five docume

- Page 7 and 8:

TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE i INTRODU

- Page 9 and 10:

N-Nitrosodimethylamine 401 N-Nitros

- Page 11 and 12:

Hot Spots Unit Risk and Cancer Pote

- Page 13 and 14:

Hot Spots Unit Risk and Cancer Pote

- Page 15 and 16:

Hot Spots Unit Risk and Cancer Pote

- Page 17 and 18:

Additional ATES and PETS documents

- Page 19 and 20:

data. If several data sets (dose an

- Page 21 and 22:

US EPA Calculation of Carcinogenic

- Page 23 and 24:

exposure to a concentration of 1 µ

- Page 25 and 26:

incidences for each of the dose lev

- Page 27 and 28:

computes the surface area of a sphe

- Page 29 and 30:

Comparison of Hot Spots Cancer Unit

- Page 31 and 32:

Gold, L., de Veciana, M., Backman,

- Page 33 and 34:

Animal Studies Rats Woutersen et al

- Page 35 and 36:

ased on sufficient evidence of carc

- Page 37 and 38:

ACETAMIDE CAS No: 60-35-5 I. PHYSIC

- Page 39 and 40:

Methodology Expedited Proposition 6

- Page 41 and 42:

cancer mortality. However, US EPA (

- Page 43 and 44:

Table 2. Lung adenoma incidence in

- Page 45 and 46:

Table 3 (continued). Acrylamide-ind

- Page 47 and 48:

Robinson M, Bull RJ, Knutsen GL, Sh

- Page 49 and 50:

Also, a trend was observed correlat

- Page 51 and 52:

eported. Cause-specific expected de

- Page 53 and 54:

Bio/Dynamics Inc. conducted a study

- Page 55 and 56:

examination. Interim sacrifices wer

- Page 57 and 58:

Table 8. Tumor incidence in male an

- Page 59 and 60:

Gaffey WR and Strauss ME. 1981. A m

- Page 61 and 62:

(technical grade; 98% pure) by gava

- Page 63 and 64:

International Agency for Research o

- Page 65 and 66:

still alive in the low-dose control

- Page 67 and 68:

ANILINE CAS No: 62-53-3 I. PHYSICAL

- Page 69 and 70:

fibrosarcomas, stromal sarcomas, ca

- Page 71 and 72:

ARSENIC (INORGANIC) CAS No: 7440-38

- Page 73 and 74:

elationship between arsenic exposur

- Page 75 and 76:

al. (1988) did not induce lung tumo

- Page 77 and 78:

A risk assessment was also conducte

- Page 79 and 80:

Chen C, Chuang Y, You S, Lin T and

- Page 81 and 82:

Schrauzer G, White D, McGinness J,

- Page 83 and 84:

Table 1: Summary of epidemiologic s

- Page 85 and 86:

had at least one animal demonstrati

- Page 87 and 88:

mesothelioma, recommended lifetime

- Page 89 and 90:

National Institute for Occupational

- Page 91 and 92:

BENZENE CAS No: 71-43-2 I. PHYSICAL

- Page 93 and 94:

Animal Studies Available experiment

- Page 95 and 96:

Table 3: Summary of NTP bioassay re

- Page 97 and 98:

Table 4: Summary of benzene low-dos

- Page 99 and 100:

Maltoni C, Conti B and Cotti G. 198

- Page 101 and 102:

a benign tumor of the kidney. No ba

- Page 103 and 104:

al. (1968) found no tumors in lifet

- Page 105 and 106:

following relationship, where C(t 1

- Page 107 and 108:

Miakawa M. and Yoshida O. 1975. Pro

- Page 109 and 110:

human population and that BPDE-DNA

- Page 111 and 112:

demonstrated the tumor initiating a

- Page 113 and 114:

Table 4: Bronchoalveolar tumors fro

- Page 115 and 116:

Table 5: IARC groupings of PAHs, mi

- Page 117 and 118:

Table 6 (continued): IARC Group 3 P

- Page 119 and 120:

Potency Equivalency Factors (PEF) f

- Page 121 and 122:

This was rounded to a PEF of 0.1. 1

- Page 123 and 124:

experiment (Takayama et al., 1985)

- Page 125 and 126:

Deutsch-Wenzel RP, Brune H, Grimmer

- Page 127 and 128:

Krewski D, Thorslund T and Withey J

- Page 129 and 130:

U.S. Environmental Protection Agenc

- Page 131 and 132:

Sorahan et al. (1983) studied cance

- Page 133 and 134:

Lijinsky W. 1986. Chronic bioassay

- Page 135 and 136:

the drinking water (Schroeder and M

- Page 137 and 138:

Table II. Effective dose, upper-bou

- Page 139 and 140:

BIS(2-CHLOROETHYL)ETHER CAS No: 111

- Page 141 and 142:

IV. DERIVATION OF CANCER POTENCY Ba

- Page 143 and 144:

BIS(CHLOROMETHYL)ETHER CAS No: 542-

- Page 145 and 146:

Table 1. Bis(chloromethyl)ether-ind

- Page 147 and 148:

Drew RT, Laskin S, Kuschner M and N

- Page 149 and 150:

ates for the 1968 U.S. male populat

- Page 151 and 152:

Table 1: Incidence of primary tumor

- Page 153 and 154:

IV. DERIVATION OF CANCER POTENCY Ba

- Page 155 and 156:

National Institute of Occupational

- Page 157 and 158:

was less than 0.05 when controlling

- Page 159 and 160:

up period. The final cohort include

- Page 161 and 162:

If the cadmium-exposed workers incl

- Page 163 and 164:

on personnel records (20%); (3) eva

- Page 165 and 166:

were exposed to a continuous (23.5

- Page 167 and 168:

procedure (NLIN), the parameters we

- Page 169 and 170:

International Agency for Research o

- Page 171 and 172:

Two reports were published on cance

- Page 173 and 174:

Mendel rats, respectively), and sub

- Page 175 and 176:

Eschenbrenner A and Miller E. 1946.

- Page 177 and 178:

III. CARCINOGENIC EFFECTS Human Stu

- Page 179 and 180:

cancers, were less than expected. T

- Page 181 and 182:

and no cases of cancer (although cl

- Page 183 and 184:

There was a statistically significa

- Page 185 and 186:

NTP (1982a) also conducted an carci

- Page 187 and 188:

Several pathologists have independe

- Page 189 and 190:

hepatocellular adenoma/carcinoma tu

- Page 191 and 192:

carcinogenic potency may decline in

- Page 193 and 194:

Cochrane W, Singh J and Miles W. 19

- Page 195 and 196:

North Atlantic Treaty Organization,

- Page 197 and 198:

CHLORINATED PARAFFINS (average chai

- Page 199 and 200:

ased on dose-response data for beni

- Page 201 and 202:

chloroform in drinking water with k

- Page 203 and 204:

Overall, the present epidemiologica

- Page 205 and 206:

female dogs received toothpaste bas

- Page 207 and 208:

Calculated q 1 * values from the ab

- Page 209 and 210:

Hogan MD, Chi Py, Hoel DG and Mitch

- Page 211 and 212:

Table 1. Study design summary for N

- Page 213 and 214:

V. REFERENCES California Environmen

- Page 215 and 216:

toluidine. Followup of this subcoho

- Page 217 and 218:

feeding studies on by NCI (1979) us

- Page 219 and 220:

CHROMIUM (HEXAVALENT) CAS No: 18540

- Page 221 and 222:

expected rate may be inflated becau

- Page 223 and 224:

Oral Borneff et al. (1968) exposed

- Page 225 and 226:

CREOSOTE (COAL TAR-DERIVED) CAS No:

- Page 227 and 228:

from an inhalation exposure study (

- Page 229 and 230:

U.S. Environmental Protection Agenc

- Page 231 and 232:

Table 1. Study design summary for N

- Page 233 and 234:

Methodology Expedited Proposition 6

- Page 235 and 236:

Table 1. Experimental design for ca

- Page 237 and 238:

Hazardous Substance Data Bank (HSDB

- Page 239 and 240:

Table 1: Tumor induction in Fischer

- Page 241 and 242:

Hazardous Substance Data Bank (HSDB

- Page 243 and 244:

Table 1. Experimental design of 2,4

- Page 245 and 246:

Methodology Expedited Proposition 6

- Page 247 and 248:

Additional analysis of these data b

- Page 249 and 250:

IV. DERIVATION OF CANCER POTENCY Ba

- Page 251 and 252:

Jackson RJ, Greene CJ, Thomas JT, M

- Page 253 and 254:

Table 1. Tumor incidence in rats ex

- Page 255 and 256:

Girard R, Tolot F, Martin P and Bou

- Page 257 and 258:

exposed more than 16 years before t

- Page 259 and 260:

interpretation of dose extrapolatio

- Page 261 and 262:

1, 1-DICHLOROETHANE CAS No: 75-34-3

- Page 263 and 264:

Table 1b. Study design for carcinog

- Page 265 and 266:

National Cancer Institute (NCI) 197

- Page 267 and 268:

mice, hepatocellular carcinoma inci

- Page 269 and 270: V. REFERENCES California Department

- Page 271 and 272: DAB/day by gavage for the life of t

- Page 273 and 274: 2,4-DINITROTOLUENE CAS No: 121-14-2

- Page 275 and 276: Ellis et al.(1979) (also reported b

- Page 277 and 278: Final Statement of Reasons for OAL,

- Page 279 and 280: to the small sample size and short

- Page 281 and 282: In an inhalation study, Torkelson e

- Page 283 and 284: V. REFERENCES American Conference o

- Page 285 and 286: EPICHLOROHYDRIN CAS No: 106-89-8 I.

- Page 287 and 288: espiratory tumors were noted in the

- Page 289 and 290: Table 4. Epichlorohydrin-induced fo

- Page 291 and 292: Konishi Y, Kawabata A, Denda A, Ike

- Page 293 and 294: exposed to arsenicals for 20 months

- Page 295 and 296: espectively (all statistically sign

- Page 297 and 298: ETHYLENE DICHLORIDE CAS No: 107-06-

- Page 299 and 300: Several factors have been suggested

- Page 301 and 302: U.S. Environmental Protection Agenc

- Page 303 and 304: myelogenous leukemias (4 and 8 year

- Page 305 and 306: statistically significant. CDHS not

- Page 307 and 308: combined with the incidence in the

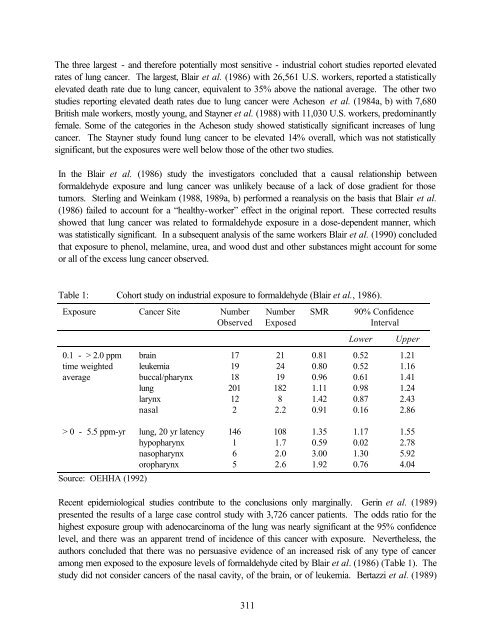

- Page 309 and 310: incidence of primary brain tumors.

- Page 311 and 312: Table 6 (continued): Organ/Sex Mali

- Page 313 and 314: An Upper 95% Confidence Limit (UCL)

- Page 315 and 316: ETHYLENE THIOUREA (ETU) CAS No: 96-

- Page 317 and 318: male and female rats. Tumor inciden

- Page 319: FORMALDEHYDE CAS No: 50-00-0 I. PHY

- Page 323 and 324: Methodology In developing a spectru

- Page 325 and 326: Casanova M, Morgan KT, Steinhagen W

- Page 327 and 328: Tobe M, Kaneko T, Uchida Y, Kamata

- Page 329 and 330: Table 1. Hexachlorobenzene-induced

- Page 331 and 332: 50 pups (F 1 ) of each sex were ran

- Page 333 and 334: Ertürk E, Lambrecht RW, Peters HA,

- Page 335 and 336: Table 1. Liver hepatoma incidence i

- Page 337 and 338: 1988). An airborne unit risk factor

- Page 339 and 340: HYDRAZINE CAS No: 302-01-2 I. PHYSI

- Page 341 and 342: Methodology Inhalation A linearized

- Page 343 and 344: LEAD AND LEAD COMPOUNDS (INORGANIC)

- Page 345 and 346: and other occupational carcinogens

- Page 347 and 348: y inhalation is similar for rats an

- Page 349 and 350: Goyer RA. 1992. Nephrotoxicity and

- Page 351 and 352: LINDANE (g-Hexachlorocyclohexane) C

- Page 353 and 354: Using these relationships, a human

- Page 355 and 356: METHYL TERT-BUTYL ETHER (MTBE) CAS

- Page 357 and 358: Tumor incidences according to the r

- Page 359 and 360: kidney changes indicative of chroni

- Page 361 and 362: Interspecies scaling for oral doses

- Page 363 and 364: Table 4 (continued): Dose Response

- Page 365 and 366: Experimental Pathology Laboratories

- Page 367 and 368: Animal Studies Male and female HaM/

- Page 369 and 370: Gold L, Sawyer C, Magaw R, Backman

- Page 371 and 372:

Using the statistical tests (one-ta

- Page 373 and 374:

Table 1: Methylene chloride-induced

- Page 375 and 376:

Significant treatment-related incre

- Page 377 and 378:

National Toxicology Program (NTP) 1

- Page 379 and 380:

noted; however, the study duration

- Page 381 and 382:

Crump KS, Howe RB, Van Landingham C

- Page 383 and 384:

Table 1. Michler’s ketone-induced

- Page 385 and 386:

NICKEL AND NICKEL COMPOUNDS CAS No:

- Page 387 and 388:

the high exposure group was 14.0. A

- Page 389 and 390:

male and 121 female rats, was expos

- Page 391 and 392:

2.1 - 2.6 × 10 -4 (µg/m 3 ) -1 .

- Page 393 and 394:

U.S. Environmental Protection Agenc

- Page 395 and 396:

The increased incidence of bladder

- Page 397 and 398:

A linearized multistage procedure w

- Page 399 and 400:

N-NITROSO-N-METHYLETHYLAMINE CAS No

- Page 401 and 402:

Hazardous Substance Data Bank (HSDB

- Page 403 and 404:

propylamine in drinking water at 0.

- Page 405 and 406:

N-NITROSODIETHYLAMINE CAS No: 55-18

- Page 407 and 408:

Table 2. Treatment groups, concentr

- Page 409 and 410:

California Department of Health Ser

- Page 411 and 412:

animals and the second generation t

- Page 413 and 414:

ationale for selection of the OEHHA

- Page 415 and 416:

A unit risk value based upon air co

- Page 417 and 418:

N-NITROSODIPHENYLAMINE CAS No: 86-3

- Page 419 and 420:

Methodology Dosage estimates of NDP

- Page 421 and 422:

Crump KS, Howe RB. 1984. The multis

- Page 423 and 424:

Table 1. P-Nitrosodiphenylamine-ind

- Page 425 and 426:

N-NITROSOMORPHOLINE CAS No: 59-89-2

- Page 427 and 428:

IV. DERIVATION OF CANCER POTENCY Ba

- Page 429 and 430:

N-NITROSOPIPERIDINE CAS No: 100-75-

- Page 431 and 432:

Table 3. N-Nitrosopiperidine-induce

- Page 433 and 434:

Crump KS, Howe RB, Van Landingham C

- Page 435 and 436:

testicular tumors were noted in the

- Page 437 and 438:

PARTICULATE MATTER FROM DIESEL-FUEL

- Page 439 and 440:

etired railroad workers who had had

- Page 441 and 442:

employment (χ 2 test for trend: p

- Page 443 and 444:

elevated smoking-adjusted risk esti

- Page 445 and 446:

Table 1 (continued): Reference Miln

- Page 447 and 448:

Table 1 (continued): Reference Damb

- Page 449 and 450:

Table 1 (continued): Reference Burn

- Page 451 and 452:

Table 1 (continued): Reference Raff

- Page 453 and 454:

Table 1 (continued): Epidemiologica

- Page 455 and 456:

Table 1 (continued): Epidemiologica

- Page 457 and 458:

Table 1 (continued): Reference Wegm

- Page 459 and 460:

Animal Studies Section 6.1 (Animal

- Page 461 and 462:

The variability, or heterogeneity,

- Page 463 and 464:

estimate for those studies for whic

- Page 465 and 466:

Figure 1: Estimates of Relative Ris

- Page 467 and 468:

q 1 * = Excess relative risk × CA

- Page 469 and 470:

Table 3: Number of Workers in the E

- Page 471 and 472:

u nexposed workers at zero concentr

- Page 473 and 474:

for each µg/m 3 of diesel exhaust

- Page 475 and 476:

Table 4: Values from Unit Risk for

- Page 477 and 478:

their findings that a reasonable es

- Page 479 and 480:

Garshick E, Schenker M, Woskie S an

- Page 481 and 482:

Lewis T, Green, FH MW, Burg J and L

- Page 483 and 484:

Rothman K. 1986. Modern epidemiolog

- Page 485 and 486:

PENTACHLOROPHENOL CAS No: 87-86-5 I

- Page 487 and 488:

The default lifespan for mice is 10

- Page 489 and 490:

documented. An excess risk from ski

- Page 491 and 492:

B6C3F 1 mice and F344/N rats were e

- Page 493 and 494:

This model, rather than a time depe

- Page 495 and 496:

POLYCHLORINATED BIPHENYLS (PCBs) CA

- Page 497 and 498:

several benign adenomatous lesions

- Page 499 and 500:

Ito et al. (1973) exposed groups of

- Page 501 and 502:

could not be characterized by chlor

- Page 503 and 504:

exposure (all pathways and mixtures

- Page 505 and 506:

National Toxicology Program 1993. T

- Page 507 and 508:

Table 1. Potassium bromate-induced

- Page 509 and 510:

1,3-PROPANE SULTONE CAS No: 1120-71

- Page 511 and 512:

IV. DERIVATION OF CANCER POTENCY Ba

- Page 513 and 514:

PROPYLENE OXIDE CAS No: 75-56-9 I.

- Page 515 and 516:

oxide. In the NTP carcinogenicity s

- Page 517 and 518:

1,1,2,2-TETRACHLOROETHANE CAS No: 7

- Page 519 and 520:

assumed a body weight of 70 kg and

- Page 521 and 522:

total); an untreated control group

- Page 523 and 524:

TOLUENE DIISOCYANATE CAS No: 26471-

- Page 525 and 526:

Animal Studies The National Toxicol

- Page 527 and 528:

Mortillaro PT and Schiavon M. 1982.

- Page 529 and 530:

male or female rats. Increases in h

- Page 531 and 532:

TRICHLOROETHYLENE CAS No: 79-01-6 I

- Page 533 and 534:

A mortality analysis of a cohort of

- Page 535 and 536:

elative to that of the controls whi

- Page 537 and 538:

applied or metabolized. The range o

- Page 539 and 540:

Katz RM and Jowett D. 1981. Female

- Page 541 and 542:

10,000 ppm 2,4,6-trichlorophenol in

- Page 543 and 544:

IV. DERIVATION OF CANCER POTENCY Ba

- Page 545 and 546:

Bionetics Research Laboratories. 19

- Page 547 and 548:

control; females: 6/10 exposed, 0/1

- Page 549 and 550:

over controls (p < 0.04). Other tum

- Page 551 and 552:

was increased (100/314 exposed vs.

- Page 553 and 554:

Table 3. Cancer potency estimates f

- Page 555 and 556:

Crouch E. 1983. Uncertainties in in

- Page 557 and 558:

VINYL CHLORIDE CAS No: 75-01-4 I. P

- Page 559 and 560:

Table 1 (continued): A Summary of E

- Page 561 and 562:

al., 1983). Histopathology of all o

- Page 563 and 564:

Table 3: Tumor incidences in 100 pp

- Page 565 and 566:

experiment, animals were exposed to

- Page 567 and 568:

Experiment BT1 Most previous risk a

- Page 569 and 570:

No statistical analyses of mortalit

- Page 571 and 572:

Table 11 gives unit risk estimates

- Page 573 and 574:

Bertazzi PA, Villa A, Foa V, Saia B

- Page 575 and 576:

Nicholson WJ, Hammond EC, Seidman H

- Page 577 and 578:

immunotoxicity, reproductive toxici

- Page 579 and 580:

scheme. TEFs for two major noncance

- Page 581 and 582:

NATO/CCMS (1988a) Pilot Study on In

- Page 583 and 584:

Table 2 Toxicity Equivalency Factor

- Page 585 and 586:

Table 4 A Comparison of CTEF- and I

- Page 587 and 588:

Office of Environmental Health Haza

- Page 589 and 590:

Group 4: The agent is probably not

- Page 591 and 592:

TECHNICAL SUPPORT DOCUMENT FOR DESC

- Page 593 and 594:

US EPA IRIS Inhalation Unit Risk an

- Page 595 and 596:

TECHNICAL SUPPORT DOCUMENT FOR DESC

- Page 597 and 598:

as appropriate, and revise IRIS fil

- Page 599 and 600:

Chemical Exposure Route Study Type

- Page 601 and 602:

Chemical Exposure Route Study Type

- Page 603 and 604:

Chemical Exposure Route Study Type

- Page 605 and 606:

Methyl tert-butyl ether p. 5: Added