Reproduction in Domestic Animals

Reproduction in Domestic Animals

Reproduction in Domestic Animals

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

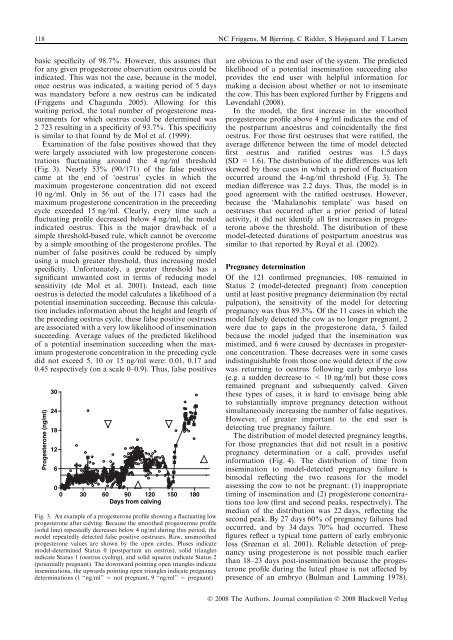

118 NC Friggens, M Bjerr<strong>in</strong>g, C Ridder, S Højsgaard and T Larsenbasic specificity of 98.7%. However, this assumes thatfor any given progesterone observation oestrus could be<strong>in</strong>dicated. This was not the case, because <strong>in</strong> the model,once oestrus was <strong>in</strong>dicated, a wait<strong>in</strong>g period of 5 dayswas mandatory before a new oestrus can be <strong>in</strong>dicated(Friggens and Chagunda 2005). Allow<strong>in</strong>g for thiswait<strong>in</strong>g period, the total number of progesterone measurementsfor which oestrus could be determ<strong>in</strong>ed was2 723 result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a specificity of 93.7%. This specificityis similar to that found by de Mol et al. (1999).Exam<strong>in</strong>ation of the false positives showed that theywere largely associated with low progesterone concentrationsfluctuat<strong>in</strong>g around the 4 ng ⁄ ml threshold(Fig. 3). Nearly 53% (90 ⁄ 171) of the false positivescame at the end of ‘oestrus’ cycles <strong>in</strong> which themaximum progesterone concentration did not exceed10 ng ⁄ ml. Only <strong>in</strong> 56 out of the 171 cases had themaximum progesterone concentration <strong>in</strong> the preceed<strong>in</strong>gcycle exceeded 15 ng ⁄ ml. Clearly, every time such afluctuat<strong>in</strong>g profile decreased below 4 ng ⁄ ml, the model<strong>in</strong>dicated oestrus. This is the major drawback of asimple threshold-based rule, which cannot be overcomeby a simple smooth<strong>in</strong>g of the progesterone profiles. Thenumber of false positives could be reduced by simplyus<strong>in</strong>g a much greater threshold, thus <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g modelspecificity. Unfortunately, a greater threshold has asignificant unwanted cost <strong>in</strong> terms of reduc<strong>in</strong>g modelsensitivity (de Mol et al. 2001). Instead, each timeoestrus is detected the model calculates a likelihood of apotential <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation succeed<strong>in</strong>g. Because this calculation<strong>in</strong>cludes <strong>in</strong>formation about the height and length ofthe preced<strong>in</strong>g oestrus cycle, these false positive oestrusesare associated with a very low likelihood of <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ationsucceed<strong>in</strong>g. Average values of the predicted likelihoodof a potential <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation succeed<strong>in</strong>g when the maximumprogesterone concentration <strong>in</strong> the preced<strong>in</strong>g cycledid not exceed 5, 10 or 15 ng ⁄ ml were: 0.01, 0.17 and0.45 respectively (on a scale 0–0.9). Thus, false positivesProgesterone (ng/ml)30241812600 30 60 90 120 150 180Days from calv<strong>in</strong>gFig. 3. An example of a progesterone profile show<strong>in</strong>g a fluctuat<strong>in</strong>g lowprogesterone after calv<strong>in</strong>g. Because the smoothed progesterone profile(solid l<strong>in</strong>e) repeatedly decreases below 4 ng/ml dur<strong>in</strong>g this period, themodel repeatedly detected false positive oestruses. Raw, unsmoothedprogesterone values are shown by the open circles. Pluses <strong>in</strong>dicatemodel-determ<strong>in</strong>ed Status 0 (postpartum an oestrus), solid triangles<strong>in</strong>dicate Status 1 (oestrus cycl<strong>in</strong>g), and solid squares <strong>in</strong>dicate Status 2(potentially pregnant). The downward po<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g open triangles <strong>in</strong>dicate<strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ations, the upwards po<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g open triangles <strong>in</strong>dicate pregnancydeterm<strong>in</strong>ations (1 ‘‘ng/ml’’ = not pregnant, 9 ‘‘ng/ml’’ = pregnant)are obvious to the end user of the system. The predictedlikelihood of a potential <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation succeed<strong>in</strong>g alsoprovides the end user with helpful <strong>in</strong>formation formak<strong>in</strong>g a decision about whether or not to <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>atethe cow. This has been explored further by Friggens andLøvendahl (2008).In the model, the first <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the smoothedprogesterone profile above 4 ng ⁄ ml <strong>in</strong>dicates the end ofthe postpartum anoestrus and co<strong>in</strong>cidentally the firstoestrus. For those first oestruses that were ratified, theaverage difference between the time of model detectedfirst oestrus and ratified oestrus was 1.5 days(SD = 1.6). The distribution of the differences was leftskewed by those cases <strong>in</strong> which a period of fluctuationoccurred around the 4-ng ⁄ ml threshold (Fig. 3). Themedian difference was 2.2 days. Thus, the model is <strong>in</strong>good agreement with the ratified oestruses. However,because the ‘Mahalanobis template’ was based onoestruses that occurred after a prior period of lutealactivity, it did not identify all first <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> progesteroneabove the threshold. The distribution of thesemodel-detected durations of postpartum anoestrus wassimilar to that reported by Royal et al. (2002).Pregnancy determ<strong>in</strong>ationOf the 121 confirmed pregnancies, 108 rema<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>Status 2 (model-detected pregnant) from conceptionuntil at least positive pregnancy determ<strong>in</strong>ation (by rectalpalpation), the sensitivity of the model for detect<strong>in</strong>gpregnancy was thus 89.3%. Of the 11 cases <strong>in</strong> which themodel falsely detected the cow as no longer pregnant, 2were due to gaps <strong>in</strong> the progesterone data, 5 failedbecause the model judged that the <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation wasmistimed, and 6 were caused by decreases <strong>in</strong> progesteroneconcentration. These decreases were <strong>in</strong> some cases<strong>in</strong>dist<strong>in</strong>guishable from those one would detect if the cowwas return<strong>in</strong>g to oestrus follow<strong>in</strong>g early embryo loss(e.g. a sudden decrease to < 10 ng ⁄ ml) but these cowsrema<strong>in</strong>ed pregnant and subsequently calved. Giventhese types of cases, it is hard to envisage be<strong>in</strong>g ableto substantially improve pregnancy detection withoutsimultaneously <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the number of false negatives.However, of greater important to the end user isdetect<strong>in</strong>g true pregnancy failure.The distribution of model detected pregnancy lengths,for those pregnancies that did not result <strong>in</strong> a positivepregnancy determ<strong>in</strong>ation or a calf, provides useful<strong>in</strong>formation (Fig. 4). The distribution of time from<strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation to model-detected pregnancy failure isbimodal reflect<strong>in</strong>g the two reasons for the modelassess<strong>in</strong>g the cow to not be pregnant: (1) <strong>in</strong>appropriatetim<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation and (2) progesterone concentrationstoo low (first and second peaks, respectively). Themedian of the distribution was 22 days, reflect<strong>in</strong>g thesecond peak. By 27 days 60% of pregnancy failures hadoccurred, and by 34 days 70% had occurred. Thesefigures reflect a typical time pattern of early embryonicloss (Sreenan et al. 2001). Reliable detection of pregnancyus<strong>in</strong>g progesterone is not possible much earlierthan 18–23 days post-<strong>in</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ation because the progesteroneprofile dur<strong>in</strong>g the luteal phase is not affected bypresence of an embryo (Bulman and Lamm<strong>in</strong>g 1978).Ó 2008 The Authors. Journal compilation Ó 2008 Blackwell Verlag