- Page 2 and 3: Reproduction in Domestic AnimalsOff

- Page 5 and 6: Reproductionin Domestic AnimalsTabl

- Page 7 and 8: Minitüb:ProductsforArtificial Inse

- Page 9 and 10: Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 1-7

- Page 11 and 12: Embryo Biotechnologies in Farm Anim

- Page 13 and 14: Embryo Biotechnologies in Farm Anim

- Page 15 and 16: Embryo Biotechnologies in Farm Anim

- Page 17 and 18: Ethical Models for Studying Reprodu

- Page 19 and 20: Ethical Models for Studying Reprodu

- Page 21 and 22: Ethical Models for Studying Reprodu

- Page 23 and 24: Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 15-2

- Page 25 and 26: Dietary Pollutants as Risk Factors

- Page 27 and 28: Dietary Pollutants as Risk Factors

- Page 29 and 30: Dietary Pollutants as Risk Factors

- Page 31 and 32: Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Supp. 2), 23-30

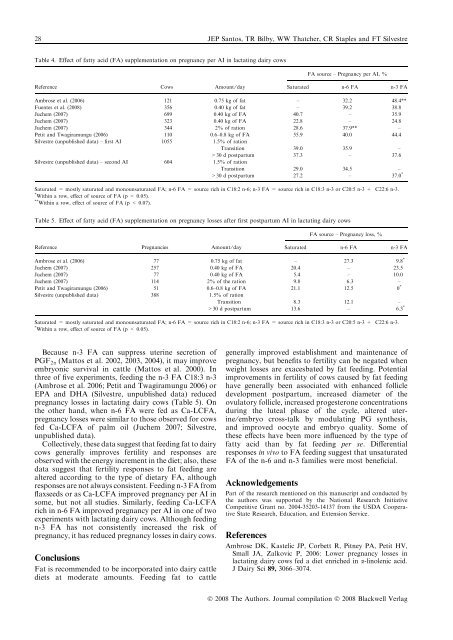

- Page 33 and 34: Factors Influencing Reproduction in

- Page 35: Factors Influencing Reproduction in

- Page 39 and 40: Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 31-3

- Page 41 and 42: GH and IGF-I in Cattle and Pigs 33h

- Page 43 and 44: GH and IGF-I in Cattle and Pigs 35h

- Page 45 and 46: GH and IGF-I in Cattle and Pigs 37B

- Page 47: GH and IGF-I in Cattle and Pigs 39R

- Page 51 and 52: Seasonality of Reproduction in Mamm

- Page 53 and 54: Seasonality of Reproduction in Mamm

- Page 55 and 56: Seasonality of Reproduction in Mamm

- Page 57 and 58: Dominant Follicle Selection in Cows

- Page 59 and 60: Dominant Follicle Selection in Cows

- Page 61 and 62: Dominant Follicle Selection in Cows

- Page 63 and 64: Dominant Follicle Selection in Cows

- Page 65 and 66: Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 57-6

- Page 67 and 68: Regulation of Luteal Function 59and

- Page 69 and 70: Regulation of Luteal Function 61bov

- Page 71 and 72: Regulation of Luteal Function 63(+/

- Page 73 and 74: Regulation of Luteal Function 65sys

- Page 75 and 76: Captive Breeding of Cheetahs in Sou

- Page 77 and 78: Captive Breeding of Cheetahs in Sou

- Page 79 and 80: Captive Breeding of Cheetahs in Sou

- Page 81 and 82: Captive Breeding of Cheetahs in Sou

- Page 83 and 84: Non-invasive Monitoring of Hormones

- Page 85 and 86: Non-invasive Monitoring of Hormones

- Page 87 and 88:

Non-invasive Monitoring of Hormones

- Page 89 and 90:

Non-invasive Monitoring of Hormones

- Page 91 and 92:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 83-8

- Page 93 and 94:

Biotechnology Methods for Preservin

- Page 95 and 96:

Biotechnology Methods for Preservin

- Page 97 and 98:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 89-9

- Page 99 and 100:

Genetic Improvement of Dairy Cow Re

- Page 101 and 102:

Genetic Improvement of Dairy Cow Re

- Page 103 and 104:

Genetic Improvement of Dairy Cow Re

- Page 105 and 106:

Nutrient Prioritization and Fertili

- Page 107 and 108:

Nutrient Prioritization and Fertili

- Page 109 and 110:

Nutrient Prioritization and Fertili

- Page 111 and 112:

Nutrient Prioritization and Fertili

- Page 113 and 114:

CL-Endometrium-Embryo Interactions

- Page 115 and 116:

CL-Endometrium-Embryo Interactions

- Page 117 and 118:

CL-Endometrium-Embryo Interactions

- Page 119 and 120:

CL-Endometrium-Embryo Interactions

- Page 121 and 122:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 113-

- Page 123 and 124:

Reproductive Status Assessed by Mil

- Page 125 and 126:

Reproductive Status Assessed by Mil

- Page 127 and 128:

Reproductive Status Assessed by Mil

- Page 129 and 130:

Reproductive Status Assessed by Mil

- Page 131 and 132:

Genetic Aspects of Reproduction in

- Page 133 and 134:

Genetic Aspects of Reproduction in

- Page 135 and 136:

Genetic Aspects of Reproduction in

- Page 137 and 138:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 129-

- Page 139 and 140:

Nutritional Interactions and Reprod

- Page 141 and 142:

Nutritional Interactions and Reprod

- Page 143 and 144:

Nutritional Interactions and Reprod

- Page 145 and 146:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 137-

- Page 147 and 148:

Developmental Capabilities of Prepu

- Page 149 and 150:

Developmental Capabilities of Prepu

- Page 151 and 152:

Developmental Capabilities of Prepu

- Page 153 and 154:

Reproductive Physiology, Pathology

- Page 155 and 156:

Reproductive Physiology, Pathology

- Page 157 and 158:

Reproductive Physiology, Pathology

- Page 159 and 160:

Reproduction of Domestic Ferret 151

- Page 161 and 162:

Reproduction of Domestic Ferret 153

- Page 163 and 164:

Reproduction of Domestic Ferret 155

- Page 165 and 166:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 157-

- Page 167 and 168:

Canine Anoestrus, Oestrous Inductio

- Page 169 and 170:

Canine Anoestrus, Oestrous Inductio

- Page 171 and 172:

Canine Anoestrus, Oestrous Inductio

- Page 173 and 174:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 165-

- Page 175 and 176:

The Ethics and Role of AI in Dogs 1

- Page 177 and 178:

The Ethics and Role of AI in Dogs 1

- Page 179 and 180:

The Ethics and Role of AI in Dogs 1

- Page 181 and 182:

Control of Fertility in Females by

- Page 183 and 184:

Control of Fertility in Females by

- Page 185 and 186:

Control of Fertility in Females by

- Page 187 and 188:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 179-

- Page 189 and 190:

Controlling Animal Populations Usin

- Page 191 and 192:

Controlling Animal Populations Usin

- Page 193 and 194:

Controlling Animal Populations Usin

- Page 195 and 196:

Recombinant Gonadotropins in Assist

- Page 197 and 198:

Recombinant Gonadotropins in Assist

- Page 199 and 200:

Recombinant Gonadotropins in Assist

- Page 201 and 202:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 193-

- Page 203 and 204:

Farm Animals Embryonic Stem Cells 1

- Page 205 and 206:

Farm Animals Embryonic Stem Cells 1

- Page 207 and 208:

Farm Animals Embryonic Stem Cells 1

- Page 209 and 210:

Reproduction in Domestic Buffalo 20

- Page 211 and 212:

Reproduction in Domestic Buffalo 20

- Page 213 and 214:

Reproduction in Domestic Buffalo 20

- Page 215 and 216:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 207-

- Page 217 and 218:

Postpartum Ovarian Activity in Sout

- Page 219 and 220:

Postpartum Ovarian Activity in Sout

- Page 221 and 222:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 213-

- Page 223 and 224:

Mother-Offspring Interactions 215an

- Page 225 and 226:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 217-

- Page 227 and 228:

Reproduction Augmentation in Yak an

- Page 229 and 230:

Reproduction Augmentation in Yak an

- Page 231 and 232:

Reproduction Augmentation in Yak an

- Page 233 and 234:

Follicles and Mares 2251982). Simil

- Page 235 and 236:

Follicles and Mares 227Studies invo

- Page 237 and 238:

Follicles and Mares 229dominant fol

- Page 239 and 240:

Follicles and Mares 231trus, spring

- Page 241 and 242:

Proteins in Early Equine Conceptuse

- Page 243 and 244:

Proteins in Early Equine Conceptuse

- Page 245 and 246:

Proteins in Early Equine Conceptuse

- Page 247 and 248:

Follicular and Oocyte Competence un

- Page 249 and 250:

Follicular and Oocyte Competence un

- Page 251 and 252:

Follicular and Oocyte Competence un

- Page 253 and 254:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 245-

- Page 255 and 256:

Fertilization in the Porcine Fallop

- Page 257 and 258:

Fertilization in the Porcine Fallop

- Page 259 and 260:

Fertilization in the Porcine Fallop

- Page 261 and 262:

Mastitis in Post-Partum Dairy Cows

- Page 263 and 264:

Mastitis in Post-Partum Dairy Cows

- Page 265 and 266:

Mastitis in Post-Partum Dairy Cows

- Page 267 and 268:

Mastitis in Post-Partum Dairy Cows

- Page 269 and 270:

Embryo ⁄ Foetal Losses in Ruminan

- Page 271 and 272:

Embryo ⁄ Foetal Losses in Ruminan

- Page 273 and 274:

Embryo ⁄ Foetal Losses in Ruminan

- Page 275 and 276:

Embryo ⁄ Foetal Losses in Ruminan

- Page 277 and 278:

Death Ligand and Receptor Pig Ovari

- Page 279 and 280:

Death Ligand and Receptor Pig Ovari

- Page 281 and 282:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 273-

- Page 283:

Lactocrine Programming of Uterine D

- Page 286 and 287:

278 FF Bartol, AA Wiley and CA Bagn

- Page 288 and 289:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 280-

- Page 290 and 291:

282 KC Caires, JA Schmidt, AP Olive

- Page 292 and 293:

284 KC Caires, JA Schmidt, AP Olive

- Page 294 and 295:

286 KC Caires, JA Schmidt, AP Olive

- Page 296 and 297:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 288-

- Page 298 and 299:

290 I Dobrinskisuccessful also betw

- Page 300 and 301:

292 I DobrinskiCreemers LB, Meng X,

- Page 302 and 303:

294 I DobrinskiOkutsu T, Suzuki K,

- Page 304 and 305:

296 N Rawlings, ACO Evans, RK Chand

- Page 306 and 307:

298 N Rawlings, ACO Evans, RK Chand

- Page 308 and 309:

300 N Rawlings, ACO Evans, RK Chand

- Page 310 and 311:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 302-

- Page 312 and 313:

304 A Dinnyes, XC Tian and X Yanggr

- Page 314 and 315:

306 A Dinnyes, XC Tian and X YangIn

- Page 316 and 317:

308 A Dinnyes, XC Tian and X YangHo

- Page 318 and 319:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 310-

- Page 320 and 321:

312 RC Bott, DT Clopton and AS Cupp

- Page 322 and 323:

314 RC Bott, DT Clopton and AS Cupp

- Page 324 and 325:

316 RC Bott, DT Clopton and AS Cupp

- Page 326 and 327:

318 BK Whitlock, JA Daniel, RR Wilb

- Page 328 and 329:

320 BK Whitlock, JA Daniel, RR Wilb

- Page 330 and 331:

322 BK Whitlock, JA Daniel, RR Wilb

- Page 332 and 333:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 324-

- Page 334 and 335:

326 CR Barb, GJ Hausman and CA Lent

- Page 336 and 337:

328 CR Barb, GJ Hausman and CA Lent

- Page 338 and 339:

330 CR Barb, GJ Hausman and CA Lent

- Page 340 and 341:

332 C Galli, I Lagutina, R Duchi, S

- Page 342 and 343:

334 C Galli, I Lagutina, R Duchi, S

- Page 344 and 345:

336 C Galli, I Lagutina, R Duchi, S

- Page 346 and 347:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 338-

- Page 348 and 349:

340 D Rath and LA JohnsonCommercial

- Page 350 and 351:

342 D Rath and LA JohnsonThe Commer

- Page 352 and 353:

344 D Rath and LA JohnsonX- and Y-b

- Page 354 and 355:

346 D Rath and LA JohnsonWalker SK,

- Page 356 and 357:

348 JM Vazquez, J Roca, MA Gil, C C

- Page 358 and 359:

350 JM Vazquez, J Roca, MA Gil, C C

- Page 360 and 361:

352 JM Vazquez, J Roca, MA Gil, C C

- Page 362 and 363:

354 JM Vazquez, J Roca, MA Gil, C C

- Page 364 and 365:

356 CBA Whitelaw, SG Lillico and T

- Page 366 and 367:

358 CBA Whitelaw, SG Lillico and T

- Page 368 and 369:

360 ACO Evans, N Forde, GM O’Gorm

- Page 370 and 371:

362 ACO Evans, N Forde, GM O’Gorm

- Page 372 and 373:

364 ACO Evans, N Forde, GM O’Gorm

- Page 374 and 375:

366 ACO Evans, N Forde, GM O’Gorm

- Page 376 and 377:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 368-

- Page 378 and 379:

370 JP Kastelic and JC Thundathilsp

- Page 380 and 381:

372 JP Kastelic and JC Thundathilme

- Page 382 and 383:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 374-

- Page 384 and 385:

376 GC AlthouseTable 1. Potential s

- Page 386 and 387:

378 GC Althousesemen to the domesti

- Page 388 and 389:

380 B Leboeuf, JA Delgadillo, E Man

- Page 390 and 391:

382 B Leboeuf, JA Delgadillo, E Man

- Page 392 and 393:

384 B Leboeuf, JA Delgadillo, E Man

- Page 394 and 395:

Reprod Dom Anim 43 (Suppl. 2), 386-

- Page 396 and 397:

388 N Kostereva and M-C HofmannFig.

- Page 398 and 399:

390 N Kostereva and M-C HofmannMMPs

- Page 400 and 401:

392 N Kostereva and M-C HofmannTado

- Page 402 and 403:

394 P Mermillod, R Dalbie` s-Tran,

- Page 404 and 405:

396 P Mermillod, R Dalbie` s-Tran,

- Page 406 and 407:

398 P Mermillod, R Dalbie` s-Tran,

- Page 408 and 409:

400 P Mermillod, R Dalbie` s-Tran,

- Page 410 and 411:

402 K Kikuchi, N Kashiwazaki, T Nag

- Page 412 and 413:

404 K Kikuchi, N Kashiwazaki, T Nag

- Page 414 and 415:

406 K Kikuchi, N Kashiwazaki, T Nag

- Page 416 and 417:

408 B ObackNumber of publications20

- Page 418 and 419:

410 B ObackReprogramming Ability of

- Page 420 and 421:

412 B Obackstudies have shown that

- Page 422 and 423:

414 B ObackFig. 4. Climbing mount e

- Page 424 and 425:

416 B ObackRenard JP, Maruotti J, J

- Page 426 and 427:

418 P Loi, K Matzukawa, G Ptak, Y N

- Page 428 and 429:

420 P Loi, K Matzukawa, G Ptak, Y N

- Page 430 and 431:

422 P Loi, K Matzukawa, G Ptak, Y N

- Page 434:

Table of Contents Volume 43 · Supp