Reproduction in Domestic Animals

Reproduction in Domestic Animals

Reproduction in Domestic Animals

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

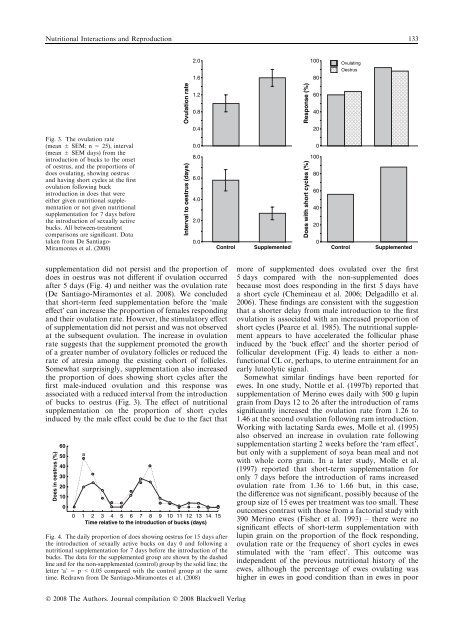

Nutritional Interactions and <strong>Reproduction</strong> 1332.01.610080Ovulat<strong>in</strong>gOestrusOvulation rate1.20.8Response (%)60400.420Fig. 3. The ovulation rate(mean ± SEM; n = 25), <strong>in</strong>terval(mean ± SEM days) from the<strong>in</strong>troduction of bucks to the onsetof oestrus, and the proportions ofdoes ovulat<strong>in</strong>g, show<strong>in</strong>g oestrusand hav<strong>in</strong>g short cycles at the firstovulation follow<strong>in</strong>g buck<strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>in</strong> does that wereeither given nutritional supplementationor not given nutritionalsupplementation for 7 days beforethe <strong>in</strong>troduction of sexually activebucks. All between-treatmentcomparisons are significant. Datataken from De Santiago-Miramontes et al. (2008)Interval to oestrus (days)0.08.06.04.02.00.0Does with short cycles (%)0100806040200Control Supplemented Control Supplementedsupplementation did not persist and the proportion ofdoes <strong>in</strong> oestrus was not different if ovulation occurredafter 5 days (Fig. 4) and neither was the ovulation rate(De Santiago-Miramontes et al. 2008). We concludedthat short-term feed supplementation before the ‘maleeffect’ can <strong>in</strong>crease the proportion of females respond<strong>in</strong>gand their ovulation rate. However, the stimulatory effectof supplementation did not persist and was not observedat the subsequent ovulation. The <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> ovulationrate suggests that the supplement promoted the growthof a greater number of ovulatory follicles or reduced therate of atresia among the exist<strong>in</strong>g cohort of follicles.Somewhat surpris<strong>in</strong>gly, supplementation also <strong>in</strong>creasedthe proportion of does show<strong>in</strong>g short cycles after thefirst male-<strong>in</strong>duced ovulation and this response wasassociated with a reduced <strong>in</strong>terval from the <strong>in</strong>troductionof bucks to oestrus (Fig. 3). The effect of nutritionalsupplementation on the proportion of short cycles<strong>in</strong>duced by the male effect could be due to the fact thatDoes <strong>in</strong> oestrus (%)6050403020100a0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15Time relative to the <strong>in</strong>troduction of bucks (days)Fig. 4. The daily proportion of does show<strong>in</strong>g oestrus for 15 days afterthe <strong>in</strong>troduction of sexually active bucks on day 0 and follow<strong>in</strong>g anutritional supplementation for 7 days before the <strong>in</strong>troduction of thebucks. The data for the supplemented group are shown by the dashedl<strong>in</strong>e and for the non-supplemented (control) group by the solid l<strong>in</strong>e; theletter ‘a’ = p < 0.05 compared with the control group at the sametime. Redrawn from De Santiago-Miramontes et al. (2008)more of supplemented does ovulated over the first5 days compared with the non-supplemented doesbecause most does respond<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the first 5 days havea short cycle (Chem<strong>in</strong>eau et al. 2006; Delgadillo et al.2006). These f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs are consistent with the suggestionthat a shorter delay from male <strong>in</strong>troduction to the firstovulation is associated with an <strong>in</strong>creased proportion ofshort cycles (Pearce et al. 1985). The nutritional supplementappears to have accelerated the follicular phase<strong>in</strong>duced by the ‘buck effect’ and the shorter period offollicular development (Fig. 4) leads to either a nonfunctionalCL or, perhaps, to uter<strong>in</strong>e entra<strong>in</strong>ment for anearly luteolytic signal.Somewhat similar f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs have been reported forewes. In one study, Nottle et al. (1997b) reported thatsupplementation of Mer<strong>in</strong>o ewes daily with 500 g lup<strong>in</strong>gra<strong>in</strong> from Days 12 to 26 after the <strong>in</strong>troduction of ramssignificantly <strong>in</strong>creased the ovulation rate from 1.26 to1.46 at the second ovulation follow<strong>in</strong>g ram <strong>in</strong>troduction.Work<strong>in</strong>g with lactat<strong>in</strong>g Sarda ewes, Molle et al. (1995)also observed an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> ovulation rate follow<strong>in</strong>gsupplementation start<strong>in</strong>g 2 weeks before the ‘ram effect’,but only with a supplement of soya bean meal and notwith whole corn gra<strong>in</strong>. In a later study, Molle et al.(1997) reported that short-term supplementation foronly 7 days before the <strong>in</strong>troduction of rams <strong>in</strong>creasedovulation rate from 1.36 to 1.66 but, <strong>in</strong> this case,the difference was not significant, possibly because of thegroup size of 15 ewes per treatment was too small. Theseoutcomes contrast with those from a factorial study with390 Mer<strong>in</strong>o ewes (Fisher et al. 1993) – there were nosignificant effects of short-term supplementation withlup<strong>in</strong> gra<strong>in</strong> on the proportion of the flock respond<strong>in</strong>g,ovulation rate or the frequency of short cycles <strong>in</strong> ewesstimulated with the ‘ram effect’. This outcome was<strong>in</strong>dependent of the previous nutritional history of theewes, although the percentage of ewes ovulat<strong>in</strong>g washigher <strong>in</strong> ewes <strong>in</strong> good condition than <strong>in</strong> ewes <strong>in</strong> poorÓ 2008 The Authors. Journal compilation Ó 2008 Blackwell Verlag