Reproduction in Domestic Animals

Reproduction in Domestic Animals

Reproduction in Domestic Animals

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

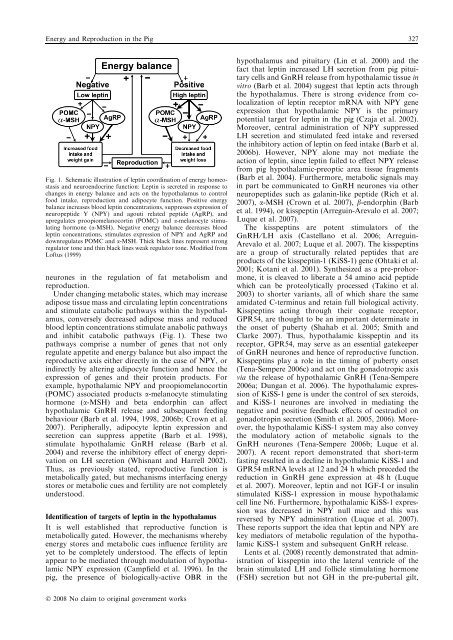

Energy and <strong>Reproduction</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Pig 327Fig. 1. Schematic illustration of lept<strong>in</strong> coord<strong>in</strong>ation of energy homeostasisand neuroendocr<strong>in</strong>e function: Lept<strong>in</strong> is secreted <strong>in</strong> response tochanges <strong>in</strong> energy balance and acts on the hypothalamus to controlfood <strong>in</strong>take, reproduction and adipocyte function. Positive energybalance <strong>in</strong>creases blood lept<strong>in</strong> concentrations, suppresses expression ofneuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti related peptide (AgRP), andupregulates proopiomelanocort<strong>in</strong> (POMC) and a-melanocyte stimulat<strong>in</strong>ghormone (a-MSH). Negative energy balance decreases bloodlept<strong>in</strong> concentrations, stimulates expression of NPY and AgRP anddownregulates POMC and a-MSH. Thick black l<strong>in</strong>es represent strongregulator tone and th<strong>in</strong> black l<strong>in</strong>es weak regulator tone. Modified fromLoftus (1999)neurones <strong>in</strong> the regulation of fat metabolism andreproduction.Under chang<strong>in</strong>g metabolic states, which may <strong>in</strong>creaseadipose tissue mass and circulat<strong>in</strong>g lept<strong>in</strong> concentrationsand stimulate catabolic pathways with<strong>in</strong> the hypothalamus,conversely decreased adipose mass and reducedblood lept<strong>in</strong> concentrations stimulate anabolic pathwaysand <strong>in</strong>hibit catabolic pathways (Fig. 1). These twopathways comprise a number of genes that not onlyregulate appetite and energy balance but also impact thereproductive axis either directly <strong>in</strong> the case of NPY, or<strong>in</strong>directly by alter<strong>in</strong>g adipocyte function and hence theexpression of genes and their prote<strong>in</strong> products. Forexample, hypothalamic NPY and proopiomelanocort<strong>in</strong>(POMC) associated products a-melanocyte stimulat<strong>in</strong>ghormone (a-MSH) and beta endorph<strong>in</strong> can affecthypothalamic GnRH release and subsequent feed<strong>in</strong>gbehaviour (Barb et al. 1994, 1998, 2006b; Crown et al.2007). Peripherally, adipocyte lept<strong>in</strong> expression andsecretion can suppress appetite (Barb et al. 1998),stimulate hypothalamic GnRH release (Barb et al.2004) and reverse the <strong>in</strong>hibitory effect of energy deprivationon LH secretion (Whisnant and Harrell 2002).Thus, as previously stated, reproductive function ismetabolically gated, but mechanisms <strong>in</strong>terfac<strong>in</strong>g energystores or metabolic cues and fertility are not completelyunderstood.Identification of targets of lept<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> the hypothalamusIt is well established that reproductive function ismetabolically gated. However, the mechanisms wherebyenergy stores and metabolic cues <strong>in</strong>fluence fertility areyet to be completely understood. The effects of lept<strong>in</strong>appear to be mediated through modulation of hypothalamicNPY expression (Campfield et al. 1996). In thepig, the presence of biologically-active OBR <strong>in</strong> thehypothalamus and pituitary (L<strong>in</strong> et al. 2000) and thefact that lept<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased LH secretion from pig pituitarycells and GnRH release from hypothalamic tissue <strong>in</strong>vitro (Barb et al. 2004) suggest that lept<strong>in</strong> acts throughthe hypothalamus. There is strong evidence from colocalizationof lept<strong>in</strong> receptor mRNA with NPY geneexpression that hypothalamic NPY is the primarypotential target for lept<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> the pig (Czaja et al. 2002).Moreover, central adm<strong>in</strong>istration of NPY suppressedLH secretion and stimulated feed <strong>in</strong>take and reversedthe <strong>in</strong>hibitory action of lept<strong>in</strong> on feed <strong>in</strong>take (Barb et al.2006b). However, NPY alone may not mediate theaction of lept<strong>in</strong>, s<strong>in</strong>ce lept<strong>in</strong> failed to effect NPY releasefrom pig hypothalamic-preoptic area tissue fragments(Barb et al. 2004). Furthermore, metabolic signals may<strong>in</strong> part be communicated to GnRH neurones via otherneuropeptides such as galan<strong>in</strong>-like peptide (Rich et al.2007), a-MSH (Crown et al. 2007), b-endorph<strong>in</strong> (Barbet al. 1994), or kisspept<strong>in</strong> (Arregu<strong>in</strong>-Arevalo et al. 2007;Luque et al. 2007).The kisspept<strong>in</strong>s are potent stimulators of theGnRH ⁄ LH axis (Castellano et al. 2006; Arregu<strong>in</strong>-Arevalo et al. 2007; Luque et al. 2007). The kisspept<strong>in</strong>sare a group of structurally related peptides that areproducts of the kisspept<strong>in</strong>-1 (KiSS-1) gene (Ohtaki et al.2001; Kotani et al. 2001). Synthesized as a pre-prohormone,it is cleaved to liberate a 54 am<strong>in</strong>o acid peptidewhich can be proteolytically processed (Tak<strong>in</strong>o et al.2003) to shorter variants, all of which share the sameamidated C-term<strong>in</strong>us and reta<strong>in</strong> full biological activity.Kisspept<strong>in</strong>s act<strong>in</strong>g through their cognate receptor,GPR54, are thought to be an important determ<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>in</strong>the onset of puberty (Shahab et al. 2005; Smith andClarke 2007). Thus, hypothalamic kisspept<strong>in</strong> and itsreceptor, GPR54, may serve as an essential gatekeeperof GnRH neurones and hence of reproductive function.Kisspept<strong>in</strong>s play a role <strong>in</strong> the tim<strong>in</strong>g of puberty onset(Tena-Sempere 2006c) and act on the gonadotropic axisvia the release of hypothalamic GnRH (Tena-Sempere2006a; Dungan et al. 2006). The hypothalamic expressionof KiSS-1 gene is under the control of sex steroids,and KiSS-1 neurones are <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> mediat<strong>in</strong>g thenegative and positive feedback effects of oestradiol ongonadotrop<strong>in</strong> secretion (Smith et al. 2005, 2006). Moreover,the hypothalamic KiSS-1 system may also conveythe modulatory action of metabolic signals to theGnRH neurones (Tena-Sempere 2006b; Luque et al.2007). A recent report demonstrated that short-termfast<strong>in</strong>g resulted <strong>in</strong> a decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> hypothalamic KiSS-1 andGPR54 mRNA levels at 12 and 24 h which preceded thereduction <strong>in</strong> GnRH gene expression at 48 h (Luqueet al. 2007). Moreover, lept<strong>in</strong> and not IGF-I or <strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong>stimulated KiSS-1 expression <strong>in</strong> mouse hypothalamiccell l<strong>in</strong>e N6. Furthermore, hypothalamic KiSS-1 expressionwas decreased <strong>in</strong> NPY null mice and this wasreversed by NPY adm<strong>in</strong>istration (Luque et al. 2007).These reports support the idea that lept<strong>in</strong> and NPY arekey mediators of metabolic regulation of the hypothalamicKiSS-1 system and subsequent GnRH release.Lents et al. (2008) recently demonstrated that adm<strong>in</strong>istrationof kisspept<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>to the lateral ventricle of thebra<strong>in</strong> stimulated LH and follicle stimulat<strong>in</strong>g hormone(FSH) secretion but not GH <strong>in</strong> the pre-pubertal gilt,Ó 2008 No claim to orig<strong>in</strong>al government works