- Page 2 and 3:

This page intentionally left blank

- Page 4 and 5:

CAMBRIDGE SYNTAX GUIDESGeneral edit

- Page 6 and 7:

PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF

- Page 8 and 9:

viContents5 The loss of object-verb

- Page 10 and 11:

viiiPrefaceThe choice of topics was

- Page 12 and 13:

Editions usedThe editions cited in

- Page 14 and 15:

xiiEditions usedBen.Rule(1) E. A. K

- Page 16 and 17:

xivEditions usedHomU 46(Nap 57) Hom

- Page 18 and 19:

xviEditions used2.20a, 2.22a, 2.26a

- Page 20 and 21:

xviiiEditions usedWooing Lord R. Mo

- Page 22 and 23:

2 The syntax of early Englishcontai

- Page 24 and 25:

4 The syntax of early Englishdiscre

- Page 26 and 27:

6 The syntax of early English1.2.1.

- Page 28 and 29:

8 The syntax of early Englishin tha

- Page 30 and 31:

10 The syntax of early Englishproba

- Page 32 and 33:

12 The syntax of early Englishc. He

- Page 34 and 35:

14 The syntax of early Englishthe l

- Page 36 and 37:

16 The syntax of early Englishappro

- Page 38 and 39:

18 The syntax of early Englishallow

- Page 40 and 41:

20 The syntax of early Englishsome

- Page 42 and 43:

22 The syntax of early Englishare f

- Page 44 and 45:

24 The syntax of early Englishthe c

- Page 46 and 47:

26 The syntax of early Englishsyste

- Page 48 and 49:

28 The syntax of early Englishfrom

- Page 50 and 51:

30 The syntax of early Englishthoug

- Page 52 and 53:

32 The syntax of early Englishæfte

- Page 54 and 55:

34 The syntax of early Englishclose

- Page 56 and 57:

36 The syntax of early Englishdown,

- Page 58 and 59:

38 The syntax of early Englishclear

- Page 60 and 61:

40 The syntax of early EnglishOld E

- Page 62 and 63:

42 The syntax of early English(8) a

- Page 64 and 65:

44 The syntax of early EnglishPrepo

- Page 66 and 67:

46 The syntax of early Englishb. &

- Page 68 and 69:

48 The syntax of early Englishb. li

- Page 70 and 71:

50 The syntax of early English(34)

- Page 72 and 73:

52 The syntax of early Englishe. æ

- Page 74 and 75:

54 The syntax of early English(43)

- Page 76 and 77:

56 The syntax of early Englishclaus

- Page 78 and 79:

58 The syntax of early English2.5.1

- Page 80 and 81:

60 The syntax of early Englishc. On

- Page 82 and 83:

62 The syntax of early Englishcompl

- Page 84 and 85:

64 The syntax of early EnglishA par

- Page 86 and 87:

66 The syntax of early Englishdiscu

- Page 88 and 89:

3An outline of Middle English synta

- Page 90 and 91:

70 The syntax of early Englishprese

- Page 92 and 93:

72 The syntax of early Englishbut w

- Page 94 and 95:

74 The syntax of early English(8)

- Page 96 and 97:

76 The syntax of early English(15)

- Page 98 and 99:

78 The syntax of early Englishpassi

- Page 100 and 101:

80 The syntax of early Englishprece

- Page 102 and 103:

82 The syntax of early Englishthe o

- Page 104 and 105:

84 The syntax of early English(45)

- Page 106 and 107:

86 The syntax of early Englishwhich

- Page 108 and 109:

88 The syntax of early Englishimpli

- Page 110 and 111:

90 The syntax of early English(65)

- Page 112 and 113:

92 The syntax of early EnglishThe u

- Page 114 and 115:

94 The syntax of early EnglishAs in

- Page 116 and 117:

96 The syntax of early EnglishA com

- Page 118 and 119:

98 The syntax of early Englishand f

- Page 121:

An outline of Middle English syntax

- Page 124 and 125:

4The Verb-Second constraint and its

- Page 126 and 127:

106 The syntax of early English(4)

- Page 128 and 129:

108 The syntax of early English(15)

- Page 130 and 131:

110 The syntax of early EnglishSuch

- Page 132 and 133:

112 The syntax of early Englishallo

- Page 134 and 135:

114 The syntax of early EnglishC-Ve

- Page 136 and 137:

116 The syntax of early English(42)

- Page 138 and 139:

118 The syntax of early English(50)

- Page 140 and 141:

120 The syntax of early Englishnega

- Page 142 and 143:

122 The syntax of early Englishin t

- Page 144 and 145:

124 The syntax of early English(65)

- Page 146 and 147:

126 The syntax of early English(72)

- Page 148 and 149:

128 The syntax of early Englishpron

- Page 150 and 151:

130 The syntax of early Englishdate

- Page 152 and 153:

132 The syntax of early EnglishKroc

- Page 154 and 155:

134 The syntax of early Englishrath

- Page 156 and 157:

136 The syntax of early Englishwere

- Page 158 and 159:

5The loss of object-verb word order

- Page 160 and 161:

140 The syntax of early EnglishWhil

- Page 162 and 163:

142 The syntax of early Englishnon-

- Page 164 and 165:

144 The syntax of early EnglishAll

- Page 166 and 167:

146 The syntax of early Englishrega

- Page 168 and 169:

148 The syntax of early English‘T

- Page 170 and 171:

150 The syntax of early Englishthos

- Page 172 and 173:

152 The syntax of early Englishthe

- Page 174 and 175: 154 The syntax of early English(45)

- Page 176 and 177: 156 The syntax of early EnglishThe

- Page 178 and 179: 158 The syntax of early EnglishLet

- Page 180 and 181: 160 The syntax of early EnglishThe

- Page 182 and 183: 162 The syntax of early EnglishIt i

- Page 184 and 185: 164 The syntax of early EnglishIn t

- Page 186 and 187: 166 The syntax of early English(68)

- Page 188 and 189: 168 The syntax of early EnglishWe a

- Page 190 and 191: 170 The syntax of early Englishidea

- Page 192 and 193: 172 The syntax of early Englishdata

- Page 194 and 195: 174 The syntax of early Englishmore

- Page 196 and 197: 176 The syntax of early EnglishAnot

- Page 198 and 199: 178 The syntax of early EnglishIt i

- Page 200 and 201: 6Verb-particles in Old and Middle E

- Page 202 and 203: 182 The syntax of early Englishto t

- Page 204 and 205: 184 The syntax of early English(5)

- Page 206 and 207: 186 The syntax of early English6.3.

- Page 208 and 209: 188 The syntax of early EnglishVerb

- Page 210 and 211: 190 The syntax of early Englishc. a

- Page 212 and 213: 192 The syntax of early EnglishIt i

- Page 214 and 215: 194 The syntax of early Englishclau

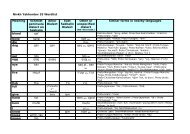

- Page 216 and 217: 196 The syntax of early EnglishTabl

- Page 218 and 219: 198 The syntax of early English1994

- Page 220 and 221: 200 The syntax of early English(38)

- Page 222 and 223: 202 The syntax of early Englishstil

- Page 226 and 227: 206 The syntax of early Englishbeyo

- Page 228 and 229: 208 The syntax of early Englishb. 7

- Page 230 and 231: 210 The syntax of early EnglishTher

- Page 232 and 233: 212 The syntax of early English1008

- Page 234 and 235: 214 The syntax of early Englishan i

- Page 236 and 237: 216 The syntax of early EnglishHist

- Page 238 and 239: 218 The syntax of early EnglishIt i

- Page 240 and 241: 220 The syntax of early Englishphra

- Page 242 and 243: 222 The syntax of early EnglishFor

- Page 244 and 245: 224 The syntax of early Englishin (

- Page 246 and 247: 226 The syntax of early EnglishOld

- Page 248 and 249: 228 The syntax of early EnglishTabl

- Page 250 and 251: 230 The syntax of early English(22a

- Page 252 and 253: 232 The syntax of early Englishmatr

- Page 254 and 255: 234 The syntax of early English(27)

- Page 256 and 257: 236 The syntax of early Englishfunc

- Page 258 and 259: 238 The syntax of early Englishto V

- Page 260 and 261: 240 The syntax of early Englishaffe

- Page 262 and 263: 242 The syntax of early Englishchan

- Page 264 and 265: 244 The syntax of early English(36a

- Page 266 and 267: 246 The syntax of early Englishc. I

- Page 268 and 269: 248 The syntax of early EnglishAppe

- Page 270 and 271: 250 The syntax of early EnglishAppe

- Page 272 and 273: Appendix Ctype of inf. predicate cl

- Page 274 and 275:

Appendix C (cont.)type of inf. pred

- Page 276 and 277:

8The history of the ‘easy-to-plea

- Page 278 and 279:

258 The syntax of early English‘e

- Page 280 and 281:

260 The syntax of early EnglishHere

- Page 282 and 283:

262 The syntax of early Englishcorr

- Page 284 and 285:

264 The syntax of early Englishread

- Page 286 and 287:

266 The syntax of early Englishposi

- Page 288 and 289:

268 The syntax of early Englishthis

- Page 290 and 291:

270 The syntax of early EnglishThe

- Page 292 and 293:

272 The syntax of early English(55)

- Page 294 and 295:

274 The syntax of early EnglishThis

- Page 296 and 297:

276 The syntax of early Englishduri

- Page 298 and 299:

278 The syntax of early Englishthes

- Page 300 and 301:

280 The syntax of early EnglishThey

- Page 302 and 303:

282 The syntax of early English(84)

- Page 304 and 305:

9Grammaticalization and grammar cha

- Page 306 and 307:

286 The syntax of early EnglishThe

- Page 308 and 309:

288 The syntax of early Englishstru

- Page 310 and 311:

290 The syntax of early Englishvers

- Page 312 and 313:

292 The syntax of early EnglishThus

- Page 314 and 315:

294 The syntax of early Englishresu

- Page 316 and 317:

296 The syntax of early Englishprec

- Page 318 and 319:

298 The syntax of early Englishchan

- Page 320 and 321:

300 The syntax of early English(13)

- Page 322 and 323:

302 The syntax of early English[bec

- Page 324 and 325:

304 The syntax of early Englishdepe

- Page 326 and 327:

306 The syntax of early EnglishWe f

- Page 328 and 329:

308 The syntax of early Englishstat

- Page 330 and 331:

310 The syntax of early Englishcann

- Page 332 and 333:

312 The syntax of early EnglishTher

- Page 334 and 335:

314 The syntax of early Englishfar

- Page 336 and 337:

316 The syntax of early Englishdeta

- Page 338 and 339:

318 The syntax of early English(37)

- Page 340 and 341:

Appendix (Fischer 1994a)A1 A2object

- Page 342 and 343:

ReferencesAdams J. N. 1994a. Wacker

- Page 344 and 345:

324 ReferencesBybee, Joan, Revere P

- Page 346 and 347:

326 References1995. The Distinction

- Page 348 and 349:

328 ReferencesHopper, Paul and Eliz

- Page 350 and 351:

330 References(ed.) 1999. The Cambr

- Page 352 and 353:

332 Referencesand Perfect Tense Aux

- Page 354 and 355:

334 ReferencesStockwell, Robert P.

- Page 356 and 357:

IndexA-bar movement see wh-movement

- Page 358 and 359:

338 Indexinput-matching 12-15interl

- Page 360 and 361:

340 IndexOld English (cont.)and Wes