Seeing clearly: Frame Semantic, Psycholinguistic, and Cross ...

Seeing clearly: Frame Semantic, Psycholinguistic, and Cross ...

Seeing clearly: Frame Semantic, Psycholinguistic, and Cross ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

CHAPTER 2. A FRAME SEMANTIC ANALYSIS 56<br />

uses patterns of alternation of argument structure to group verbs <strong>and</strong> then attempts to<br />

describe these groups in semantic terms. She says,<br />

This work is guided by the assumption that the behaviorofaverb, particularly<br />

with respect to the expression <strong>and</strong> interpretation of its arguments, is to<br />

a large extent determined by its meaning. Thus verb behavior can be used effectively<br />

to probe for linguistically relevant pertinent aspects of verb meaning.<br />

. . . [This book] should help pave the way toward the development ofatheoryof<br />

lexical knowledge. Ideally, such a theory must provide linguistically motivated<br />

lexical entries for verbs which incorporate representation of verb meaning <strong>and</strong><br />

which allow the meanings of verbs to be properly associated with the syntactic<br />

expressions of their arguments. (p.1)<br />

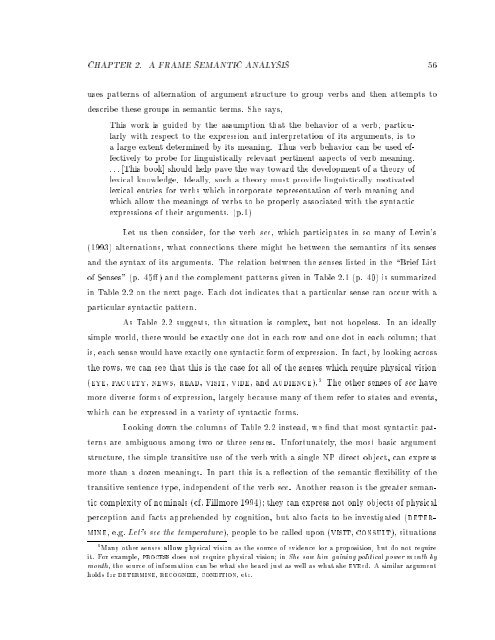

Let us then consider, for the verb see, which participates in so many of Levin's<br />

(1993) alternations, what connections there might bebetween the semantics of its senses<br />

<strong>and</strong> the syntax of its arguments. The relation between the senses listed in the \Brief List<br />

of Senses" (p. 45 ) <strong>and</strong> the complement patterns given in Table 2.1 (p. 40) is summarized<br />

in Table 2.2 on the next page. Each dot indicates that a particular sense can occur with a<br />

particular syntactic pattern.<br />

As Table 2.2 suggests, the situation is complex, but not hopeless. In an ideally<br />

simple world, there would be exactly one dot in each row <strong>and</strong> one dot in each column; that<br />

is, each sense would have exactly one syntactic form of expression. In fact, by looking across<br />

the rows, we can see that this is the case for all of the senses which require physical vision<br />

(eye, faculty, news, read, visit, vide, <strong>and</strong> audience). 6 The other senses of see have<br />

more diverse forms of expression, largely because many of them refer to states <strong>and</strong> events,<br />

which canbeexpressedinavariety ofsyntactic forms.<br />

Looking down the columns of Table 2.2 instead, we nd that most syntactic pat-<br />

terns are ambiguous among two or three senses. Unfortunately, the most basic argument<br />

structure, the simple transitive use of the verb with a single NP direct object, can express<br />

more than a dozen meanings. In part this is a re ection of the semantic exibility of the<br />

transitive sentence type, independent of the verb see. Another reason is the greater seman-<br />

tic complexity of nominals (cf. Fillmore 1994); they can express not only objects of physical<br />

perception <strong>and</strong> facts apprehended by cognition, but also facts to be investigated (deter-<br />

mine, e.g.Let's see the temperature), people to be called upon (visit, consult), situations<br />

6 Many other senses allow physical vision as the source of evidence for a proposition, but do not require<br />

it. For example, process does not require physical vision; in She saw him gaining political power month by<br />

month, the source of information can be what she heard just as well as what she eyeed. A similar argument<br />

holds for determine, recognize, condition, etc.