ADB_book_18 April.qxp - Himalayan Document Centre - icimod

ADB_book_18 April.qxp - Himalayan Document Centre - icimod

ADB_book_18 April.qxp - Himalayan Document Centre - icimod

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

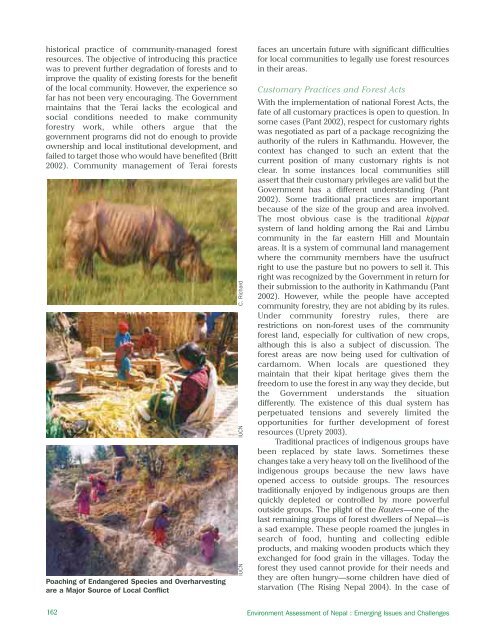

historical practice of community-managed forestresources. The objective of introducing this practicewas to prevent further degradation of forests and toimprove the quality of existing forests for the benefitof the local community. However, the experience sofar has not been very encouraging. The Governmentmaintains that the Terai lacks the ecological andsocial conditions needed to make communityforestry work, while others argue that thegovernment programs did not do enough to provideownership and local institutional development, andfailed to target those who would have benefited (Britt2002). Community management of Terai forestsPoaching of Endangered Species and Overharvestingare a Major Source of Local ConflictIUCN IUCN C. Richardfaces an uncertain future with significant difficultiesfor local communities to legally use forest resourcesin their areas.Customary Practices and Forest ActsWith the implementation of national Forest Acts, thefate of all customary practices is open to question. Insome cases (Pant 2002), respect for customary rightswas negotiated as part of a package recognizing theauthority of the rulers in Kathmandu. However, thecontext has changed to such an extent that thecurrent position of many customary rights is notclear. In some instances local communities stillassert that their customary privileges are valid but theGovernment has a different understanding (Pant2002). Some traditional practices are importantbecause of the size of the group and area involved.The most obvious case is the traditional kippatsystem of land holding among the Rai and Limbucommunity in the far eastern Hill and Mountainareas. It is a system of communal land managementwhere the community members have the usufructright to use the pasture but no powers to sell it. Thisright was recognized by the Government in return fortheir submission to the authority in Kathmandu (Pant2002). However, while the people have acceptedcommunity forestry, they are not abiding by its rules.Under community forestry rules, there arerestrictions on non-forest uses of the communityforest land, especially for cultivation of new crops,although this is also a subject of discussion. Theforest areas are now being used for cultivation ofcardamom. When locals are questioned theymaintain that their kipat heritage gives them thefreedom to use the forest in any way they decide, butthe Government understands the situationdifferently. The existence of this dual system hasperpetuated tensions and severely limited theopportunities for further development of forestresources (Uprety 2003).Traditional practices of indigenous groups havebeen replaced by state laws. Sometimes thesechanges take a very heavy toll on the livelihood of theindigenous groups because the new laws haveopened access to outside groups. The resourcestraditionally enjoyed by indigenous groups are thenquickly depleted or controlled by more powerfuloutside groups. The plight of the Rautes—one of thelast remaining groups of forest dwellers of Nepal—isa sad example. These people roamed the jungles insearch of food, hunting and collecting edibleproducts, and making wooden products which theyexchanged for food grain in the villages. Today theforest they used cannot provide for their needs andthey are often hungry—some children have died ofstarvation (The Rising Nepal 2004). In the case of162 Environment Assessment of Nepal : Emerging Issues and Challenges