Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The satisfaction theory 107<br />

implies (32c), in a fairly strong sense of 'imply'. On the other h<strong>and</strong> it is<br />

anything but obvious that (32c) is more plausible than (32b). However, if the<br />

argument from improbability is correct, then the two preceding statements<br />

cannot be true together, because judging that (32c) is more plausible than<br />

(32b) is tantamount to judging that (32a) implies (32c). But since these two<br />

statements are, evidently, not the same thing, the argument must be wrong.<br />

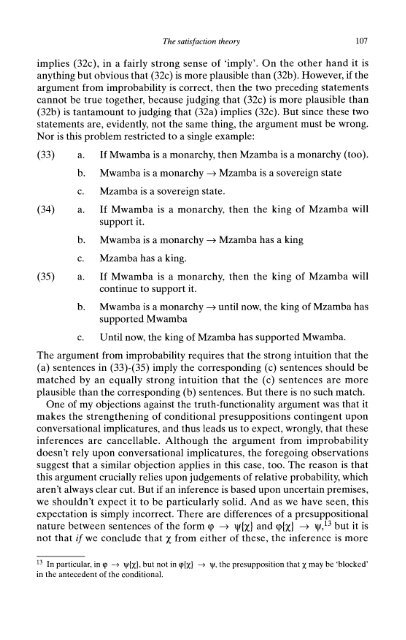

Nor is this problem restricted to a single example:<br />

(33) a. If Mwamba is a monarchy, then Mzamba is a monarchy (too).<br />

b. Mwamba is a monarchy —> ~ Mzamba is a sovereign state<br />

c. Mzamba is a sovereign state.<br />

(34) a. If Mwamba is a monarchy, then the king of Mzamba will<br />

support it.<br />

b. Mwamba is a monarchy —> ~ Mzamba has a king<br />

c. Mzamba has a king.<br />

(35) a. If Mwamba is a monarchy, then the king of Mzamba will<br />

continue to support it.<br />

b. Mwamba is a monarchy —> ~ until now, the king of Mzamba has<br />

supported Mwamba<br />

c. Until now, the king of Mzamba has supported Mwamba.<br />

The argument from improbability requires that the strong intuition that the<br />

(a) sentences in (33)-(35) imply the corresponding (c) sentences should be<br />

matched by an equally strong intuition that the (c) sentences are more<br />

plausible than the corresponding (b) sentences. But there is no such match.<br />

One of my objections against the truth-functionality argument was that it<br />

makes the strengthening of conditional presuppositions contingent upon<br />

conversational implicatures, <strong>and</strong> thus leads us to expect, wrongly, that these<br />

inferences are cancellable. Although the argument from improbability<br />

doesn't rely upon conversational implicatures, the <strong>for</strong>egoing observations<br />

suggest that a similar objection applies in this case, too. The reason is that<br />

this argument crucially relies upon judgements of relative probability, which<br />

aren't always clear cut. But if an inference is based upon uncertain premises,<br />

we shouldn't expect it to be particularly solid. And as we have seen, this<br />

expectation is simply incorrect. There are differences of a presuppositional<br />

nature between sentences of the <strong>for</strong>m ~ '!'{X} \|/{%} <strong>and</strong> ~ ,!,,13 \j/, 13 but it is<br />

not that if Z/we conclude that % X from either of these, the inference is is more<br />

13 13 In particular, in q> ~ '!'{X}, \|/{%}, but not in