Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Names 215<br />

that he himself might have been a twin. There<strong>for</strong>e, I would bracket (20b)<br />

with (20a) <strong>and</strong> (20c) with (20d); but I don't expect that these judgments will<br />

remain uncontested. This is as it may be, however, because the relevant<br />

observation is that our intuitions about the relation between John <strong>and</strong> his<br />

counterparts vary at all. Needless to say, this variation causes problems <strong>for</strong> a<br />

Kripkean analysis of names. In the present framework, by contrast, it is only<br />

to be expected.<br />

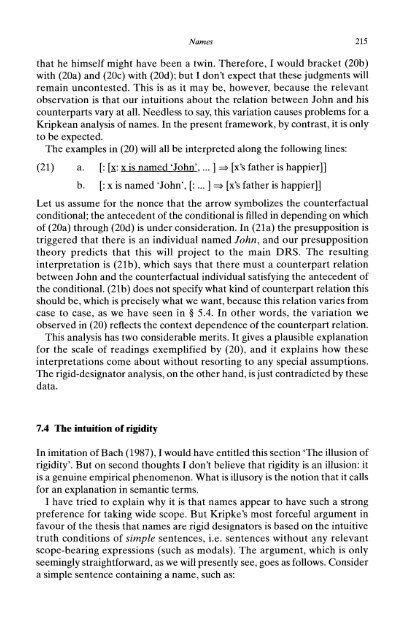

The examples in (20) will all be interpreted along the following lines:<br />

(21) a. [: [x: x is named 'John', 'John'.... ] => ~ [x's father is happier]]<br />

b. [: x is named 'John', [:... ] =$ ~ [x's father is happier]]<br />

Let us assume <strong>for</strong> the nonce that the arrow symbolizes the counterfactual<br />

conditional; the antecedent of the conditional is filled in depending on which<br />

of (20a) through (20d) is under consideration. In (21a) the presupposition is<br />

triggered that there is an individual named fohn, John, <strong>and</strong> our presupposition<br />

theory predicts that this will project to the main DRS. The resulting<br />

interpretation is (21b), which says that there must a counterpart relation<br />

between John <strong>and</strong> the counterfactual individual satisfying the antecedent of<br />

the conditional. (21b) does not specify what kind of counterpart relation this<br />

should be, which is precisely what we want, because this relation varies from<br />

case to case, as we have seen in § 5.4. In other words, the variation we<br />

observed in (20) reflects the context dependence of the counterpart relation.<br />

This analysis has two considerable merits. It gives a plausible explanation<br />

<strong>for</strong> the scale of readings exemplified by (20), <strong>and</strong> it explains how these<br />

interpretations come about without resorting to any special assumptions.<br />

The rigid-designator analysis, on the other h<strong>and</strong>, is just contradicted by these<br />

data.<br />

7.4 The intuition of rigidity<br />

In imitation of Bach (1987), I would have entitled this section 'The illusion of<br />

rigidity'. But on second thoughts I don't believe that rigidity is an illusion: it<br />

is a genuine empirical phenomenon. What is illusory is the notion that it calls<br />

<strong>for</strong> an explanation in semantic terms.<br />

I have tried to explain why it is that names appear to have such a strong<br />

preference <strong>for</strong> taking wide scope. But Kripke's most <strong>for</strong>ceful argument in<br />

favour of the thesis that names are rigid designators is based on the intuitive<br />

truth conditions of simple sentences, i.e. sentences without any relevant<br />

scope-bearing expressions (such as modals). The argument, which is only<br />

seemingly straight<strong>for</strong>ward, as we will presently see, goes as follows. Consider<br />

a simple sentence containing a name, such as: