Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Presupposition 25<br />

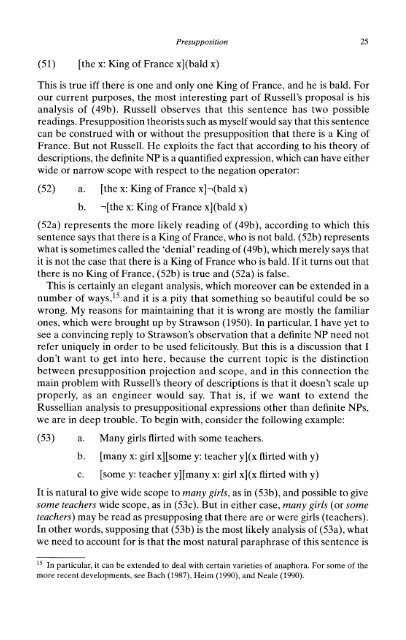

(51) [the x: King of France x](bald x)<br />

This is true iff there is one <strong>and</strong> only one King of France, <strong>and</strong> he is bald. For<br />

our current purposes, the most interesting part of Russell's proposal is his<br />

analysis of (49b). Russell observes that this sentence has two possible<br />

readings. Presupposition theorists such as myself would say that this sentence<br />

can be construed with or without the presupposition that there is a King of<br />

France. But not Russell. He exploits the fact that according to his theory of<br />

descriptions, the definite NP is a quantified expression, which can have either<br />

wide or narrow scope with respect to the negation operator:<br />

(52) a. [the x: King of France x]-(bald x],(bald x)<br />

b. ,[the -{the x: King of France x](bald x)<br />

(52a) represents the more likely reading of (49b), according to which this<br />

sentence says that there is a King of France, who is not bald. (52b) represents<br />

what is sometimes called the 'denial' reading of (49b), which merely says that<br />

it is not the case that there is a King of France who is bald. If it turns out that<br />

there is no King of France, (52b) is true <strong>and</strong> (52a) is false.<br />

This is certainly an elegant analysis, which moreover can be extended in a<br />

number of ways,15 <strong>and</strong> it is a pity that something so beautiful could be so<br />

wrong. My reasons <strong>for</strong> maintaining that it is wrong are mostly the familiar<br />

ones, which were brought up by Strawson (1950). In particular, I have yet to<br />

see a convincing reply to Strawson's observation that a definite NP need not<br />

refer uniquely in order to be used felicitously. But this is a discussion that I<br />

don't want to get into here, because the current topic is the distinction<br />

between presupposition projection <strong>and</strong> scope, <strong>and</strong> in this connection the<br />

main problem with Russell's theory of descriptions is that it doesn't scale up<br />

properly, as an engineer would say. That is, if we want to extend the<br />

Russellian analysis to presuppositional expressions other than definite NPs,<br />

we are in deep trouble. To begin with, consider the following example:<br />

(53) a. Many girls flirted with some teachers.<br />

b. [many x: girl x][some y: teacher y](x flirted with y)<br />

c. [some y: teacher y][many x: girl x](x flirted with y)<br />

It is natural to give wide scope to many girls, as in (53b), <strong>and</strong> possible to give<br />

some teachers wide scope, as in (53c). But in either case, many girls (or some<br />

teachers) may be read as presupposing that there are or were girls (teachers).<br />

In other words, supposing that (53b) is the most likely analysis of (53a), what<br />

we need to account <strong>for</strong> is that the most natural paraphrase of this sentence is<br />

15 15 In particular, it can be extended to deal with certain varieties of anaphora. For some of the<br />

more recent developments, see Bach (1987), Heim (1990), <strong>and</strong> Neale (1990).