Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Presuppositions and Pronouns - Nijmegen Centre for Semantics

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

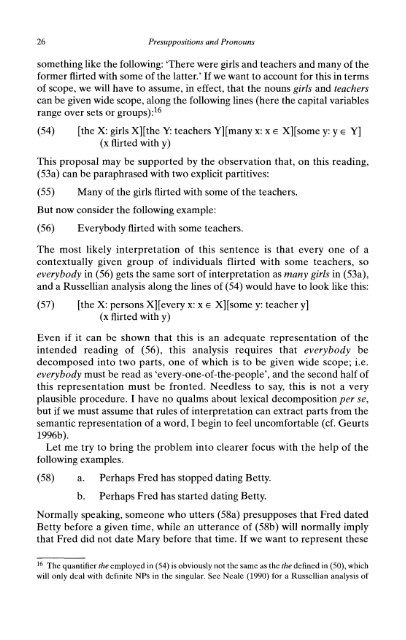

26 <strong>Presuppositions</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Pronouns</strong><br />

something like the following: 'There were girls <strong>and</strong> teachers <strong>and</strong> many of the<br />

<strong>for</strong>mer flirted with some of the latter.' If we want to account <strong>for</strong> this in terms<br />

of scope, we will have to assume, in effect, that the nouns girls <strong>and</strong> teachers<br />

can be given wide scope, along the following lines (here the capital variables<br />

range over sets or groups):16<br />

(54) [the X: girls X][the Y: teachers Y][many x: x E e X][some y: y E e Y]<br />

(x flirted with y)<br />

This proposal may be supported by the observation that, on this reading,<br />

(53a) can be paraphrased with two explicit partitives:<br />

(55) Many of the girls flirted with some of the teachers.<br />

But now consider the following example:<br />

(56) Everybody flirted with some teachers.<br />

The most likely interpretation of this sentence is that everyone of a<br />

contextually given group of individuals flirted with some teachers, so<br />

everybody in (56) gets the same sort of interpretation as many girls in (53a),<br />

<strong>and</strong> a Russellian analysis along the lines of (54) would have to look like this:<br />

(57) [the X: persons X] [every x: x E e X][some y: teacher y]<br />

(x flirted with y)<br />

Even if it can be shown that this is an adequate representation of the<br />

intended reading of (56), this analysis requires that everybody be<br />

decomposed into two parts, one of which is to be given wide scope; i.e.<br />

everybody must be read as 'every-one-of-the-people', <strong>and</strong> the second half of<br />

this representation must be fronted. Needless to say, this is not a very<br />

plausible procedure. I have no qualms about lexical decomposition per se,<br />

but if we must assume that rules of interpretation can extract parts from the<br />

semantic representation of a word, I begin to feel uncom<strong>for</strong>table (ct. (cf. Geurts<br />

1996b).<br />

Let me try to bring the problem into clearer focus with the help of the<br />

following examples.<br />

(58) a. Perhaps Fred has stopped dating Betty, Betty.<br />

b. Perhaps Fred has started dating Betty.<br />

Normally speaking, someone who utters (58a) presupposes that Fred dated<br />

Betty be<strong>for</strong>e a given time, while an utterance of (58b) will normally imply<br />

that Fred did not date Mary be<strong>for</strong>e that time. If we want to represent these<br />

16 16 The quantifier the employed in (54) is obviously not the same as the the defined denned in (50), which<br />

will only deal with definite NPs in the singular. See Neale (1990) <strong>for</strong> a Russellian analysis of